An Interview with Róza El-Hassan on the occasion of her exhibition at the Mücsarnok (Kunsthalle) in Budapest, July-September 2006

Allan Siegel: Let’s begin with a broad, very general question about curating. There are many aspects to curating–how do you see its importance.

Róza El-Hassan: It’s a very pragmatic question. The most important thing about curating is to be able to communicate about art and what artists do. Especially in Hungary, it is very important to be able to communicate our work to the public. Not all curators agree with this.

A.S.: Do you think there is a problem (in the region) that there are not enough people who have the skills to curate?

R.E.: Before the changes (ed note: in 1989) there were no curators in Hungary. There were art historians working for museums. It was not a defined field of work. I think it is a Western term: “curatorial practice.” My generation can go to the curators and propose “something.” We aren’t that different than freelance curators.

One question is that the curator [often] does not have institutional power (like an artist). Freelance curators are often in a much worse situation than artists, especially in Hungary. The other question is how to get financial support if you are a curator; those people who get financial support decide the final appearance of an exhibition. Another big problem in Budapest is that the galleries don’t have a good background for artists working in a more conceptual or progressive way.

I curated some shows or initiated some projects and for me it is sometimes even more interesting to work with other artists and to initiate independent projects. Last year I curated the‘Some Stories’ exhibition2005 : Some Stories, Kunsthalle, Wien (curatorial project with Gerald Matt and Angela Stief). in Vienna. It was a quite interesting experience. I had to solve several questions between the director of the museum (the Kunsthalle) and the other artists. I was a mediator. The concept of the show was to present women’s art from the Middle East and we tried to make it with the other artists more politically correct. It was a very good concept for Gerhard to invite me, but we ended up always in confrontation or discussions with the artists and me. Finally, it was a very good.

A.S.: Do you think the curator is a bridge between the artist and the public?

R.E.: If I work with a curator it is much more important if he or she can communicate my work or other artists’ work to the public. That would be the best case if this would happen. If it’s a good curator then this happens. For me, if a curator has an idea for a very special project then it is the same as a conceptual art work – there is no distinction between a good concept for a show and a conceptual art work because both are interventions between society and art.

I was very lucky to work with BeataBeata Hock – Beata Hock is currently a PhD candidate at the Department of Gender Studies, Central European University, Budapest. Since 2003 editor of Praesens Central European Contemporary Art Review. Her publications include: Women’s Art and Public Art: Possible Interpretive Aspects for Two Kinds of Art Practice Emerging in the Past 15 Years, Budapest: Praesens Books, 2005 as well as various freelance writings on gender, art, and literature. Her recent curatorial project was Hungarian artist Róza El-Hassan’s retrospective exhibition in Mucsarnok/Kunsthalle Budapest (2006 July-September). on my show because she could bring some order into this big group of material we exhibited here. She rationalized it and helped me to make it more communicative, not just an internal aesthetic talk.

A.S.: Your work can be seen in many museums throughout the region. Here we can see its development. What is unique in this present moment of your work?

R.E.: I haven’t for the past 3 years been working that much in the West. I focused my work on Budapest. I always felt that I worked in a very isolated situation. Before, in the 90s, I had many exhibitions in the West or internationally and then I was somehow fed up with traveling around from one exhibition to another; I thought there were never any real roots for my work. It became more important to work locally. It was a rather human necessity too. Not to work in Budapest and export all my productions to Austria or the States or to Germany but to do somehow do something locally. It was very important. But it was not just my situation; Bulgarian artists or Romanian artists have had these difficulties also. We were always invited to all kind of international shows: “Art from Eastern Europe.” But it is very important to communicate work to the local society because there was no awareness of our activities in Hungary. Four years ago there was no public, nothing. We couldn’t participate in a group show or make an exhibition.

I had a very funny experience participating two times as “the other“ from Eastern Europe and from the Middle East. It was a very similar experience when I meet artists from Cairo and they have very little local background and they jet set from Kyoto or New York to be presented as Egyptian female artists. And they also try to work locally in their hometowns.

A.S.: In terms of contemporary art here in Budapest, do you think there is enough support?

R.E.: In these days there’s better funding for restoration of historical sites and objects, which is also important, but this has to be seen as part of our tourist branch, it is not so much embedded into contemporary society. It would be possible to work [and survive] locally if we had more presence in the media or in the public and then some local collectors would collect our work. We would still need institutional support, but this comes mainly from the state.

In a personal or human way there is a lot of support here. There are very good people. I work with curators and artists, but the problem is the public or the collectors. They don’t offer support and so we always try to support each other. I don’t think it’s very different – artist or curator – we all work very close together. I don’t know if there is less necessity or little need for contemporary art or if it is just because the general financial situation in Hungary is so bad, and therefore there’s nearly no money for culture. I mean contemporary culture, which would be important for our self definition and self esteem.

A.S.: My immediate observation, looking at the exhibition, is that your work has this range. How did you go about organizing the different materials?

R.E.: The exhibition is built up in a chronological way; in the 90s, in the beginning, it was aesthetic, theoretical or hermeneutic questions. One of my favorite theoreticians was Kasimir Malevich and his idea of inspection. For me it was a space of independent existence–like some art space, some independent space where I could work and exist. Later I got in contact with this so-called contextual art and political art. We wanted to show development this way from this autonomous, abstract space to the rather subjective or narrative or contextual art. Beata and I made this reconstruction of the exhibition environment which went together with these [changing]artistic attitude.

R.E.: The exhibition is built up in a chronological way; in the 90s, in the beginning, it was aesthetic, theoretical or hermeneutic questions. One of my favorite theoreticians was Kasimir Malevich and his idea of inspection. For me it was a space of independent existence–like some art space, some independent space where I could work and exist. Later I got in contact with this so-called contextual art and political art. We wanted to show development this way from this autonomous, abstract space to the rather subjective or narrative or contextual art. Beata and I made this reconstruction of the exhibition environment which went together with these [changing]artistic attitude.

So the first space is very ‘empty’; you see this ‘abstract space’ and this is the way my work was exhibited in the 90s. I went to these big museums and they showed my work in these very clean and empty white spaces. Then also I started to work locally and on projects I initiated outside an institutional system, so the last space is more like public spaces and private spaces. The framework of art is not defined by the white walls of the museum, but rather by the context.

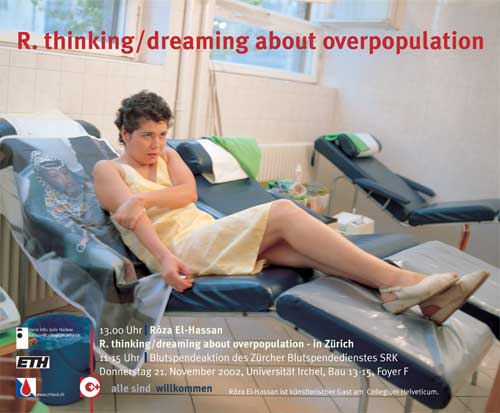

What the visitor can see is much more than a chaotic exhibition structure: objects, performance videos and huge wall texts, fence, signs, comments, blood donation performance, sitting figures and a heart made of stone dispersed in the space. Basically you see three projects in dialog with each other. In the center of it all I place a heart made of stones to “disturb” or to enrich the pure context based discourse by something that is independent of time and space and discourse.

A.S.: At a certain point an artist reaches a kind of maturity and they see their own creative process in a larger context. How do you see your work now and how do you think the public sees it?

R.E.: I am 40 years old now and I started to work when I was 20 and I didn’t think about my own work. I thought about the actual projects but I didn’t think about the interpretation of the process: the process which started in ’92 and it is now 2006. I mean the artistic process. I had no conscious attitude of my own decisions: by this I mean that I was always concerned, deeply involved in the actual project and so I didn’t compare it to the previous one, I didn’t look back. Now I see it; I have to see it because now I had this exhibition and there was no way to escape.

I have had very extreme interpretations of the exhibition. It was very funny because it opened in the summer and there were no art people around so there was mainly the general public and I gave these talks and people from the streets came–people from Budapest who are not used to dealing with contemporary art. So I had three types of comments: one is [that I am some kind of] ‘maniac’ because the work is just something which is completely irrational – like you have this stone with colored pins, this huge rock, and there is no rational reason to stick these small and tiny colored pins into the rock. So this is like an insane action. It’s one interpretation. [I have some kind of] ‘mental problem.’

I have had very extreme interpretations of the exhibition. It was very funny because it opened in the summer and there were no art people around so there was mainly the general public and I gave these talks and people from the streets came–people from Budapest who are not used to dealing with contemporary art. So I had three types of comments: one is [that I am some kind of] ‘maniac’ because the work is just something which is completely irrational – like you have this stone with colored pins, this huge rock, and there is no rational reason to stick these small and tiny colored pins into the rock. So this is like an insane action. It’s one interpretation. [I have some kind of] ‘mental problem.’

Then the other interpretation was even scarier. Some people came from the streets, and a woman said that she feels like God or other metaphysical powers are speaking to her through my works and the gift I receive is something celestial – a special way of receiving a clear view.

These are two possible interpretations when people don’t see an artwork in the system of art history.

A.S.: People who come from outside the ‘artistic sphere’ have no way to relate to what’s being presented? The public has no real tools to relate to contemporary art?

R.E.:20th century art history is a safe territory, which provides, allows us, the freedom to say that unusual acts like sticking little colored pins into a rock is part of cultural practice. This interpretation gives freedom to several social practices and behaviors, which lie outside – which are beyond – the dangerous type of monoculturural “mainstream normality.”

For me this was a little bit shocking. The third way [of seeing the exhibition] was when ‘art people’ come and then the work is completely natural. Then it is natural to stick pins in a stone because it is embedded in a cultural process. This is an expression of a formal language that began more than a 100 years ago.

I met a woman (who is a translator) when I was giving one of the artist’s talks. She was also present when the woman said that God is speaking to me and I said to her that now I have one goal to be ‘normal’ (laughs). And then this lady said to me, “but what is normal? This is a very dangerous category: to normalize the society.” ‘Normal’ society it is like a totalitarian regime if there is only one way to be normal. If people have no choice and have only insanity or normality then this is a very rigid society. Art is maybe a tool to make this tension a little bit lighter because then maybe you have room to play and to have a more relaxed discourse.

A.S.: Artists here in Hungary, like yourself, participate in an international discourse. This is something that informs your work and is part of your vocabulary. The blood donation piece is political and performative. Other work is very conceptual. How do you see the connection between these different strands?

R.E.:Artists here in Hungary, like yourself, participate in an international discourse. This is something that informs your work and is part of your vocabulary. The blood donation piece is political and performative. Other work is very conceptual. How do you see the connection between these different strands?

Artists here in Hungary, like yourself, participate in an international discourse. This is something that informs your work and is part of your vocabulary. The blood donation piece is political and performative. Other work is very conceptual. How do you see the connection between these different strands?

A.S.: This is the tension in your work……………………………….

R.E.: Yes, yes it is true.

A.S.: On the surface the blood donation is a political statement but there is something else which is part of the artistic statement which relates to this other thread. What is that?

R.E.:I lost the tools to handle this artistically in a rational way.

A.S.: Your work also poses questions about the relationship between types of art and identity.

R.E.: Identity questions are one thing, but the religious question is more difficult today, because religions today have a really big importance. If you decide to speak for Black people, or for Arab people (for Hungarian people everything is possible) then it is still this identification of your body and your soul, “what you want to show to the public or your subjective narrative, or whatever you want to show.” But what happens when you want to decide for Muslim people? It is very difficult to bring this position into contemporary art because then it is about tradition. It is very difficult to change the traditional aesthetic rules, and all of contemporary art is often about the freedom of changing rules.

R.E.: Identity questions are one thing, but the religious question is more difficult today, because religions today have a really big importance. If you decide to speak for Black people, or for Arab people (for Hungarian people everything is possible) then it is still this identification of your body and your soul, “what you want to show to the public or your subjective narrative, or whatever you want to show.” But what happens when you want to decide for Muslim people? It is very difficult to bring this position into contemporary art because then it is about tradition. It is very difficult to change the traditional aesthetic rules, and all of contemporary art is often about the freedom of changing rules.

I wanted to invite somebody from the mosque. And I started to contact people but they didn’t dare to invite an imam from the mosque in Hungary. I know him but I didn’t dare to invite him. This is the thing I need courage for.

There are thousands of non-verbal levels of behavior in the Muslim world… If you have more than one cultural background then you decide between the patterns of behaving, and this is a little bit of a difficult situation, I have to say. If you only have one cultural background (I don’t know if it is possible to live in a mono-cultural environment in our century) then you basically have one guide to behave or what to do. And if you have several you can choose also the moral decisions, private decisions of rules how to behave.

A.S.: It is very difficult to isolate yourself into one kind of environment. And in a sense you can create your own otherness. Is that true?

R.E.: Yes, of course, it is partly artificial. It is always a conscious decision. But it is quite different that everything is ruled by rational decisions. It is not just my problem as an artist or a person with a multi-cultural background, because if you go to the Arab world and a traditional environment or a local cultural environment and suddenly they switch on TV and there it is: the other. The same is for Hungary or any other place in the world where people own a TV.

It is not possible to be isolated anymore. There is a very big tension in Hungarian society; there are people who are religious and others who are not. How to relate to cultural tradition is a very big question.

A.S.: What is the cultural tradition? Who is defining it? Even the communist era is a cultural tradition. Before the changes you had an official art and then another art practice that was below the surface that was never officially recognized. How do you write the history of an artistic past?

R.E.: Then, there was no space for this art. There was no contemporary art museum. It was like oral history some times. Irwin (in Slovenia) works a lot with this topic and it’s very funny that one artist group can invent art history. They have a project to write Eastern European art history. It is not a natural political or cultural development. There are several books published on eastern European contemporary art but this is like an artistic project; like an invention it is not in the natural structure of publishing of historians and writers.

But it is also a challenge – here this safe background is missing. The system of galleries and collectors is like a safe background so that you know what you are doing; and here if somebody comes from the streets and he says that this is a ‘revelation’ – ‘a cultural, or political or religious revelation’ – then it is not a defined space, because the written art history is missing. The 20th century art history is missing so it is very challenging.

It is also challenging because in this way artists can have the possibility to have a direct affect on society because if it is completely embedded in a cultural tradition or institutional system, then it has only a place in gallery and it is completely defined. Here if I exhibit Sík Toma’s demonstration signsToma Sík, Hungarian social non-artist / social life-artist. and they say “don’t buy American products” – because the Hungarian economy will be better – [the affect is direct].

We don’t have that strong pop art tradition that puts everything in quotation marks. Here, if you put anything in a museum you don’t necessarily have this safety. If you put Mao Tse Tung on a print it might mean that you want to support him (not like the Andy Warhol print).

We have the possibility to be closer to the avant garde from the beginning of the last century because they wanted to relate to life; to bring art and life closer. So here, in a way, art and life are closer because there is no art history in the background. I try not to imagine the faces of all the art historians and aestheticians reading this statement, so it’s time to stop I guess.

A.S.: Thank you.

Mûcsarnok Kunsthalle, Budapest, August 24 and Sept 19 2006.