Lightening up the World: Documentary Mixes Soviet Propaganda, Reality Soap and Music TV.

Coal Dust (Ugol’naya Pyl’). Directed by Maria Miro (aka Maria Miroshnichenko). VGIK, Ostrov Studio, 2006. Video: 20 min, 35mm.

The twenty-minute documentary Coal Dust (Ugol’naya Pyl’) was shot by a young VGIK team in the Chelyabinsk area (located in the east of Ural Mountains) in 2005. After the shooting was completed in 2006, the director Maria Miro (Miroshnichenko) was honored at the “Window to Europe” festival in Vyborg in 2007 for the best debut. In the same year her film also won the Moscow student film festival “St. Anna” (“Svyataya Anna”) in the non fiction film category. In addition, the director of photography Nikolay Karpov won the prize for “Best Photography” at the XVII documentary festival in Yekaterinburg. Outside of Russia, the movie was shown and praised by the jury at the 50 th Leipzig DOK Festival. In my opinion these honors prove the acceptance of formal methods employed by the film. By manipulating the highly segmented and remixed footage, by over-highlighting and by using music clips, the film Coal Dust reduces the documentary to a “mockumentary.”

At the end of 2007 some of the Russian submissions for the prior Leipzig DOK Festival were shown in Berlin. I had an opportunity to watch Coal Dust as a video projection. To my knowledge, the film could not to be purchased until recently, but a small clip from the last chapter of the film was published on Rambler Vision. At the time, there was very little information on Coal Dust. Aside from the abstracts in the festival programs, I found several interviews with Maria Miro on the Russian internet, in which she talks about the making of the film and the difficulties during the shootings.

At first glance the film seems to be structured like a typical day in the life of a coal miner. It has four distinct parts or chapters. The first part shows “the wheels going round and round.” The film’s hero, Andrey Vicharev, is going to work by bike, passing a moon-like landscape, accompanied by a column of huge trucks.

The second and longest part can be seen as a social study. It shows Andrey in his surroundings, at work in the mine, with his family, in his hometown Kopejsk. This part ends with an anniversary of a serious mining accident.

The third and very short chapter shows Andrey on his way home from work. This part is characterized by a spectacular shot from a helicopter cabin with a camera focusing on the mine building. Contrary to this optimistic bird’s eye view, which at first appears to lead up to the proverbial happy ending, the film turns in another direction. The authors followed it with another part, marked by tired and resigned moods. The topic of accidents and catastrophes which concluded the second part iscarried on in the third chapter. The lift starts its “last lowering” into the “empire of shadows.” The mineworkers go on a never-ending trip on the mine’s train and get trapped in its depth.

This last chapter closes with the typical cyclical description of everyday life. It can be interpreted as pointing out the hopelessness of the situation. Interestingly, this last chapter is uncharacteristically aesthetically pleasing, featuring beautiful and artistic photographs, reminiscent of paintings. The material aesthetics of the celluloid film and the optical characteristics of the analogue 35mm film equipment combine to create rich colours, smooth contours and a wonderful bokeh. Despite these qualities, the pictures often have no connection to the main topic of the film, except for the very expressive portraits of the exhausted miners.

In terms of content, Coal Dust is a story about a simple miner. This focus becomes most obvious in the second and fourth chapters of the film: hardworking miners, frightening and rusty machinery, low wages, resignation and the prophecy of a forthcoming strike. The aforementioned protagonist, Andrey Vicharev, serves as a ferryman between the “empire of shadows” and the light trapped in the celluloid. The film’s subheading “Monologue of the young miner Andrey Vicharev” illustrates the authors’ wish to give the film authenticity and an appearance of objectivity. At the same time, we are fully aware of the deliberate dramatization in the form of staging, direction and photography.

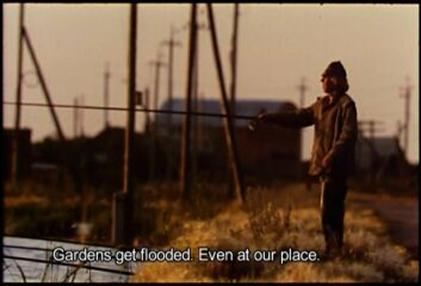

Young Andrey is not just a simple blue-collar worker, who deals with a mattock, supports the mine ceilings with wooden pylons or collects coal bits behind the huge, battered drilling machine. Andrey is one of the few younger workers. He has been working at the mine for five years now – making rounds, measuring the level of coal dust and methane in the air to make sure they do not rise to a dangerous, explosive level. His character is quiet; his speech is reserved. He reflects the coal’s negative influence on nature, but also exhibits pride of being a professional miner. At the end Andrey changes positions, becoming a supervisor rather than a regular miner. He walks through the mine alone, illuminated by a mystical blue light courtesy of Anton Safronov, who was in charge of the film’s lighting effects.

These are science fiction-like scenes. They highlight the alien position of the protagonist while at the same time depicting his apotheosis, underscoring his angelic, god-like nature. Another method of manipulating the hero is to detach his voice from his personal appearance by having him talk to us from offstage. It is questionable if the reason for this is only a technical one, since the cameraman used a soviet Konvas-2M camera without synchronized sound recording capability. Either way, since his gestures and facial expressions do not follow with his speech, it is quite hard to get an idea of his own opinion of what he said. This creates a lack of closeness or intimacy between the viewer and the protagonist, and that’s why the words of Andrey, who is no more than a puppet in the filmmaker’s hands, sound like coquettish trickery: “…but everyone has a character, and everyone thinks in his own way.”

Andrey’s fatalistic outlook as well as his analogizing of his fate to the coal dust, which motivated the title of the film, can be characterized as melodramatically (over)loaded. And in spite of the film crew’s efforts, the explosive power of this mixture, represented by Andrey, is totally lost.

Nikolay Karpov’s camera, together with the sounds of composer Andrey Doynikov, mixed by sound director Tatiana Turina, spin Andrey’s surroundings in an attempt to manipulate the picture. Throughout the film we hear high-quality acoustic moods instead of the original sounds – even simple soundslike the dribbling of water or a dog barking are often studio produced. Hence this method can be characterized as the arrangement of the highly segmented and heterogeneous original material with the objective to get punchy mosaic-like pictures.

The first scene of the film is the clearest representation of how Coal Dust was made and how it uses techniques similar to those employed in making music videos. The film begins with a picture of an aggressive cog-wheel, which is starting to turn in sync with the music. A red spot and the yellow light of a miner’s lamp act as accompaniment to the basic light. Meanwhile, a grinding sound of steel is added to the score to approximate thee original sound of the cog-wheel. Thus, an apparently homogenous, but in fact a very artificial impression of a monster wheel was created using different artistic ingredients.

There are some more examples to be found in the film, in which single cinematic components like perspective, color, light, sound or music are even more exaggerated, like in the following ventilator scene where the fast motion, unusual camera position, and the wide angle lenses are combined with the rhythmic sound made by the ventilator wings, thus resulting in over-dramatisation and over-acceleration of seemingly simple, mundane settings.

Another example of this acceleration occurs with crane sequence. The old mining machinery, witch is presented in early Soviet stock footage, is awakened and provided with new life with the aid of fast-motion technique.

The overbearing demonstration of cinematic techniques dominates the film’s plot. The viewer cannot avoid the impression that he is watching a television production, considering the use of techniques characteristic of reality television. One example of this strategy is the author’s method of cutting and compiling sequences to simulate a mine accident: a crash of coal, a red alarm light, the fire brigade accompanied by sirens hurrying to the scene of the accident.

Additionally, there is the use of choreography in the last scene of this sequence in which the camera passes over the line of firemen. Right after the camera has passed, they start to put on their uniforms and run toward the fire truck. In another scene, we see prisoners in marching formation on their way to the mine.

At the end, the manifested stagnation of the depicted reality and the resignation of the characters collide with the overall acceleration and intensification of movement. The authors effectively use film as a medium to discover, register, and most importantly, to create movement.

The juxtaposition of Dziga Vertov’s documentary Enthusiasm/Symphony of Donets Basin (1930) with Coal Dust exposes the inconsistencies of Miro’s film. Vertov produced the first Soviet documentary with synchronous audio track. Afterwards he manipulated the footage, thereby creating a dynamic, and to some extent abstract and ambivalent film, putting on stage the ambassadors of a new mankind. The ambassadors free themselves from religious oppression to become a part of the machine. Vertov manipulated the source footage in many ways, but arranged it into a concentrated and conceptually coherent avant-garde masterpiece. The numerous manipulations of the footage in Miro’s Coal Dust, in comparison to Vertov’s work, lack an express purpose, and are seemingly unrelated to the layer of the pictured reality or are often used for simple dramatization.

Did the Soviet stock footage used in the film serve as a model for the film? Coal Dust displays the old socialist symbols as well as exposes the irrational heroism of productivity and selflessness. The main character is portrayed as a representative of a certain type of human being, he is a part of the crowd. The Soviet Era echoes throughout thefilm. But is this only because miners are the chosen topic?

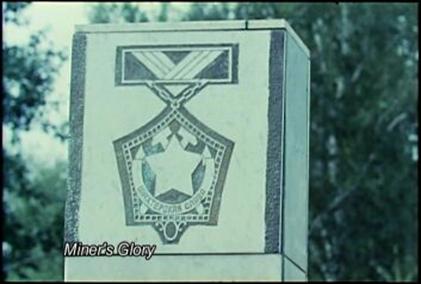

The Lenin monument, the rusty red stars and huge posters proclaiming “the greater glory of the miner’s work” in huge letters on the wall, are relics of the past. In comparison, there is a contemporary monument, a graveyard memorial to the twenty eight miners who were killed in the mining accident. The monument is a Soviet style faceless brick wall, surrounded by the staring empty eyes and resigned faces of the relatives left behind. The mine’s ex-chief, who is in fact responsible for the senseless deaths of 28 workers, makes a speech. Written on the monument is the excuse that is supposed to legitimize everything: “Miner’s glory.” Dying is a part of the profession; nobody is responsible. The film itself is not trying to reflect the circumstances of the accident in the mine, but rather joins the heroic atmosphere.

Andrey himself constructs his profession’s myth. For him, this means remaining faithful to his profession, just like his father, who suffers from lung cancer, and his grandfather.

But Andrey’s decision to become a miner seems to be much less voluntary than he wants us to believe. There is simply no alternative occupations available in this region, and people are used to their profession and its risks. The main character is a patient martyr, a prisoner of his job.

Concerning the film Coal Dust the influence of propaganda results in nothing more than the takeover of formal methods. This film does not create a utopia or an alternative. Nevertheless, the determining teleological aspects of propaganda, its sublime, futuristic qualities, are completely missing in Coal Dust. The filmmakers’ lack of a clear position evinces itself in the nostalgic use of myths, superstition and religiousness. As Andrey passes by the place of a former accident, a little cross twinkles on his neck. In this film, there is a patent conflict between the captured reality and methods of its representation. There are prominent examples of this conflict in Lukovs film Big Life (1939), a monolithic and coherent propaganda motion picture. Seven years later in the sequel Big Life 2, Lukov experiments with differed genres and some stylistic variations. Big Life 2 results in a monstrous compilation of unfitting puzzle pieces that are forced to drag out a nearly identical story line.

Coal Dust is a well-made film, featuring some excellent scenes and character portraits, and is worth seeing. But of course it is not a propaganda movie, nor is it an authentic monologue, due to the very impersonal portrayal of Andrey. It is impossible to tell what the filmmakers’ own view of the captured reality is, except for their vague sense of pity and compassion with the miners. Furthermore the author’s and producer’s fascination with technical aspects of filmmaking is more than obvious and creates an impression of deliberate overemphasis. Coal Dust is overproduced and seems to be more of a “mockumentary,” documenting something which does not exist. The resulting film virtualizes the captured reality exceedingly, until it can no longer be identified as such. The wonderful cooperation of the whole team, whose craftsmanship and aesthetic sensitivity is unquestionable, does not find its appropriate expression and loses itself somewhere between the fetish of film-making and subtle mysticism.