Russian Revolution: A Contested Legacy, 1917-2017

International Print Center, New York, October 12 – December 16, 2017

The centennial of the Russian Revolution has prompted a year long array of inter-disciplinary happenings re-examining the historical and political legacy of the 1917 watershed event. In New York alone, The Museum of Modern Art mounted a substantial collection-based exhibition titled A Revolutionary Impulse: The Rise of the Russian Avant-Garde that amassed a plethora of paintings, print media, and films made between 1912 and 1935, Columbia University launched a series of Revolution-related conferences covering subjects ranging from political science to the history of Russian Jews, while The New York Historical Society invited historian Jeremy Black to discuss significant connections between the Russian Revolution, the Great War, and the rise of modern age. Fitting neatly into this celebratory agenda, albeit on a much smaller scale, is Russian Revolution: A Contested Legacy, 1917-2017 organized at The International Print Centerin New York by Russian art historian Masha Chlenova (October 12 to December 16, 2017). Juxtaposing the work by two living Russian artists, Yevgeniy Fiks and Anton Ginzburg, with a plethora of print media from the early Soviet period, Contested Legacy examines the contemporary relevance of some of the revolution’s early objectives, focusing specifically on the emancipation of women, the rise of internationalism (a category that includes problems of racial inequality and the rights of ethnic minorities, particularly the Jews), and sexual and gay liberation.

That these “often-obscured” goals of the 1917 Revolution outlived their actual implementation, the exhibition suggests, is no reason to ignore their historical and cultural legacy.(“Russian Revolution: A Contested Legacy” Exhibition Press Release (New York: International Print Center, 2017).) The show advocates for our shared responsibility to protect individual freedoms, offering a reflection on the widespread racism, sexism, homophobia, xenophobia, and anti-Semitism in the modern-day world, and Russia in particular. Chlenova’s idea to highlight these relevant matters by invoking socio-political optimism and subsequent struggle of the early Soviet artists is provocative, while the accompanying wall labels and the catalogue essay are very well researched and intellectually rigorous. Rather than proceeding chronologically, the show is organized thematically, with each section displaying early Soviet prints next to contemporary artworks in diverse media. Yet, and despite its seemingly expansive timeline as well as the prominence of much of the Soviet art on view, Contested Legacy appears primarily as a contemporary art show, led by the work of Fiks and Ginzburg. Its thematic framework does an excellent job of illuminating the socially engaged practice of the two living Russian artists, but results in an admittedly selective and fractured account of the Russian avant-garde’s history.

That these “often-obscured” goals of the 1917 Revolution outlived their actual implementation, the exhibition suggests, is no reason to ignore their historical and cultural legacy.(“Russian Revolution: A Contested Legacy” Exhibition Press Release (New York: International Print Center, 2017).) The show advocates for our shared responsibility to protect individual freedoms, offering a reflection on the widespread racism, sexism, homophobia, xenophobia, and anti-Semitism in the modern-day world, and Russia in particular. Chlenova’s idea to highlight these relevant matters by invoking socio-political optimism and subsequent struggle of the early Soviet artists is provocative, while the accompanying wall labels and the catalogue essay are very well researched and intellectually rigorous. Rather than proceeding chronologically, the show is organized thematically, with each section displaying early Soviet prints next to contemporary artworks in diverse media. Yet, and despite its seemingly expansive timeline as well as the prominence of much of the Soviet art on view, Contested Legacy appears primarily as a contemporary art show, led by the work of Fiks and Ginzburg. Its thematic framework does an excellent job of illuminating the socially engaged practice of the two living Russian artists, but results in an admittedly selective and fractured account of the Russian avant-garde’s history.

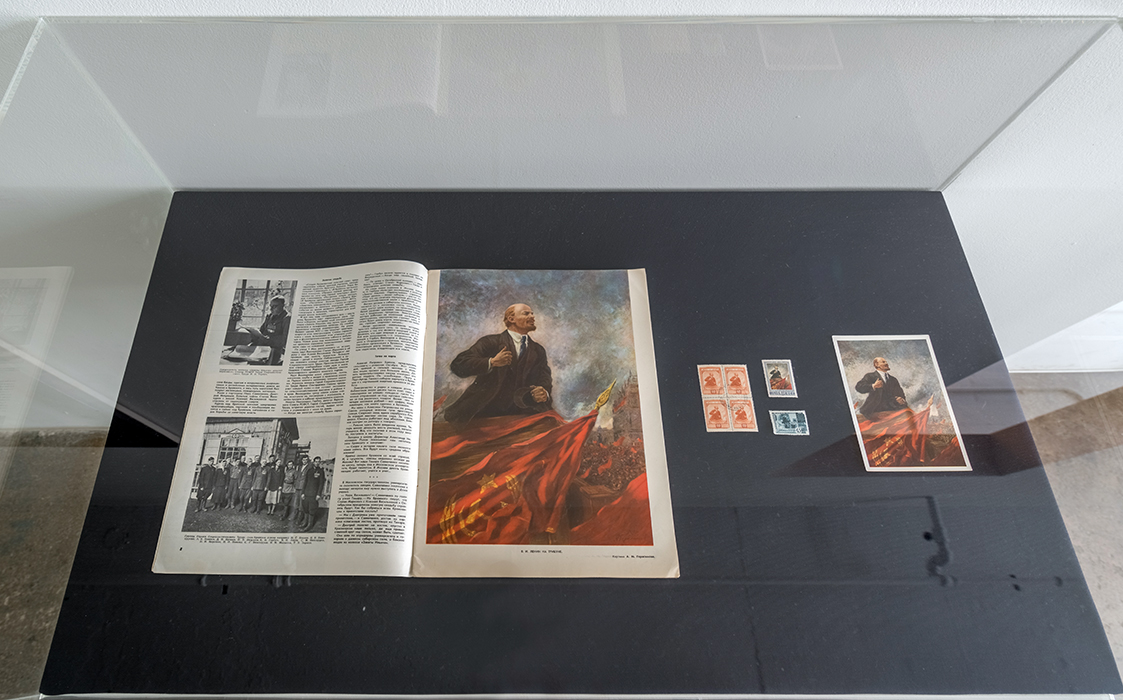

The exhibition opens with a striking 2008 oil painting by Fiks titled Leniniana no.1 (after Aleksandr Gerasimov, “V.I. Lenin on the Tribune”), which faces the entrance to the IPCNY space in Chelsea. In it, the archetypal 1930 Socialist Realist work by Gerasimov, showing Lenin enthusiastically addressing a crowd from a tribune, is transformed into a large-scale composition with the image of Lenin missing. Gerasimov’s 1930 picture became one of the most reproduced images of Lenin, printed in millions during the Soviet Union and carrying what Chlenova calls “a specific DNA of historical memory.”(Masha Chlenova, “Introduction” in Russian Revolution: A Contested Legacy, Exhibition Catalogue (New York: International Print Center, 2017), 3.) She understands the work to function as an anchor for the key strategy of the exhibition, that is its intention to take “at face value the iconic and broadly framed proclamations of Soviet revolutionary society” through printed media.(Ibid.) Moreover, Leniniana’s central position in Contested Legacy also offers a somber reflection upon the miserable fate of the Russian avant-garde under Stalin. Fiks’s removal of the legendary Bolshevik leader from a Socialist Realist icon is akin to the rhetoric of visual eradication that was to define the cultural milieu of the Soviet Union during the 1930s Great Purge, when thousands of photographs were doctored to eliminate enemies of the state.

Moving counterclockwise from Leniniana, the viewer traverses work by early Soviet and the two contemporary Russian artists arranged side-by-side and according to the four aforementioned early revolutionary goals. Soviet racial equality is represented by Fiks’ commentary on Claude McKay’s visit to Moscow in 1922, while the work of El Lissitzky and Natan Al’tman, placed in close vicinity to a 2015 Lissitzky-inspired screenprint, relates to Jewish freedom in the USSR post-1917. A brilliantly colorful print from Anton Ginzburg’s Meta-Constructivism poster series proclaiming that “Revolution Was Ruined When It Rejected Free Love” tackles Soviet female emancipation and gives agency to the working women featured on neighboring Soviet posters by Elizaveta Ignatovich, Boris Klinch, and others. Especially considering the widespread nature of sexism in modern-day Russia (readers may recall, among other recent news-worthy incidents indicating the problem, how the Weinstein scandal was trivialized on air by Dmitry Kiselyov, one of the country’s leading television hosts), these Soviet prints constitute powerful, if romanticized, voices of resistance against patriarchal domination.

Moving counterclockwise from Leniniana, the viewer traverses work by early Soviet and the two contemporary Russian artists arranged side-by-side and according to the four aforementioned early revolutionary goals. Soviet racial equality is represented by Fiks’ commentary on Claude McKay’s visit to Moscow in 1922, while the work of El Lissitzky and Natan Al’tman, placed in close vicinity to a 2015 Lissitzky-inspired screenprint, relates to Jewish freedom in the USSR post-1917. A brilliantly colorful print from Anton Ginzburg’s Meta-Constructivism poster series proclaiming that “Revolution Was Ruined When It Rejected Free Love” tackles Soviet female emancipation and gives agency to the working women featured on neighboring Soviet posters by Elizaveta Ignatovich, Boris Klinch, and others. Especially considering the widespread nature of sexism in modern-day Russia (readers may recall, among other recent news-worthy incidents indicating the problem, how the Weinstein scandal was trivialized on air by Dmitry Kiselyov, one of the country’s leading television hosts), these Soviet prints constitute powerful, if romanticized, voices of resistance against patriarchal domination.

Sexual liberation is further explored in reference to homosociality (defined as “social relations of a non-sexual nature between men”) and gay liberation (decriminalized in 1917, homosexuality was recriminalized less than a decade later, after Stalin’s rise to power). (Ibid., 6.) The exhibition’s take on gay freedoms in the USSR seems somewhat idealized—a short-lived decriminalization of male on male sex per se does not equal sexual revolution—although the proud and strong collective male body of a 1931 lithograph by Gustav Klucis titled Let’s Repay the Coal Debt to the Country gains considerable political resonance in light of Putin’s anti-LGBT agenda and the recent reports of violent gay persecuting in Chechnya. A 2013 series of wood cut blocks by Fiks’ dedicated to the founder of the modern gay right movement in the United States, Harry Hay, from 2013 offers a salient commentary on the ubiquity of sexual oppression. Concluding the exhibition—and accentuating a sense of timeliness that pervades the space—is Ginzburg’s Stargaze: Orion (2016). Originally a model for public sculpture at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow commissioned under Obama’s administration, Stargaze: Orion deploys the geometric and universalizing vocabulary of early Constructivism to create an object free of national symbolism and ideological divides. Yet the meaning of the work changed considerably, as the curator notes, in the wake of the 2016 Russian meddling in the U.S. presidential elections and the subsequent diplomatic fallout. Its idealism clashing against the volatile reality of East-West international relations, Stargaze: Orion stands as a witness to abrupt political shifts. Although the U.S. Embassy commission was realized, the idealistic nature of Ginzburg’s project brings to mind the early Constructivist utopia of Vladimir Tatlin, evident in his iconic model for the never-built Monument to the Third International (1919-1920).

Notwithstanding the scholarly rigor that must have gone into conceptualizing Contested Legacy, it is peculiar that the vast majority of the avant-garde works on view were made in the late 1920s and the early 1930s, limiting the exhibition’s chronological scope. As a result, critical questions of historical continuity between the pre- and post-1917 avant-garde are not sufficiently addressed, while the catalogue essay devotes more attention to Ginzburg and Fiks than it does to the history of early Soviet art. For instance, when discussing Anton Ginzburg’s ZAUM/ESL #7 from 2017, in which the artist invoked the pre-1917 trans-rational language of the Russian avant-garde, the essay makes no reference to Aleksei Kruchenykh (early twentieth-century Russian poet and its original author) or to questions relating to Slavic national mysticism, both of which are arguably relevant to a work examining questions relating to language and verbal expression in an increasingly globalized world.(For more on this subject, see: Gerald Janecek, Zaum: The Transrational Poetry of Russian Futurism (San Diego: San Diego State University Press, 2006).) Similarly, El Lissitzky’s Ukrainian Folk Tales from 1923 and Chad Gadya from 1922, in which the artist negotiates his own Jewish identity, are discussed in the catalogue essay without discussing the spiritual and artistic influence of his first Vitebsk teacher, Marc Chagall.(See: Yve-Alain Bois, “El Lissitzky: Radical Reversibility,” Art in America (April 1988): 160-181.) These and other omissions may seem pedantic to those familiar with the history of Russian modern art, but they arguably affect the experience of those viewers who are not.

Notwithstanding the scholarly rigor that must have gone into conceptualizing Contested Legacy, it is peculiar that the vast majority of the avant-garde works on view were made in the late 1920s and the early 1930s, limiting the exhibition’s chronological scope. As a result, critical questions of historical continuity between the pre- and post-1917 avant-garde are not sufficiently addressed, while the catalogue essay devotes more attention to Ginzburg and Fiks than it does to the history of early Soviet art. For instance, when discussing Anton Ginzburg’s ZAUM/ESL #7 from 2017, in which the artist invoked the pre-1917 trans-rational language of the Russian avant-garde, the essay makes no reference to Aleksei Kruchenykh (early twentieth-century Russian poet and its original author) or to questions relating to Slavic national mysticism, both of which are arguably relevant to a work examining questions relating to language and verbal expression in an increasingly globalized world.(For more on this subject, see: Gerald Janecek, Zaum: The Transrational Poetry of Russian Futurism (San Diego: San Diego State University Press, 2006).) Similarly, El Lissitzky’s Ukrainian Folk Tales from 1923 and Chad Gadya from 1922, in which the artist negotiates his own Jewish identity, are discussed in the catalogue essay without discussing the spiritual and artistic influence of his first Vitebsk teacher, Marc Chagall.(See: Yve-Alain Bois, “El Lissitzky: Radical Reversibility,” Art in America (April 1988): 160-181.) These and other omissions may seem pedantic to those familiar with the history of Russian modern art, but they arguably affect the experience of those viewers who are not.

They also appear symptomatic of a broader trend present in American scholarship dealing with Russian avant-garde, in which post-1917 politicized art tends to be privileged over earlier examples of Russian modernism. To give a recent example: when the Museum of Modern Art organized the aforementioned Revolutionary Impulse earlier this year, they concluded the exhibition by inviting a panel of four art historians to offer their critical responses (among them was also Masha Chlenova) to works featured in the exhibition. Even though Revolutionary Impulse included a number of important paintings and drawings made in 1912 (including early examples of Cubo-Futurist and Rayonist painting), the lectures delivered at MoMA focused almost exclusively on art made after 1917. Consequently, the critical role such early avant-garde artists as Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, to mention just a couple, is being lessened in favor of a Constructivism-dominated discourse that, for the most part, remains firmly anchored in post-revolutionary Soviet Union. While it is important to recognize that the IPCNY exhibition is ostensibly not a historical survey of Russian avant-garde art and that its focus remains on printed media—the production of which flourished significantly after the Revolution—one wonders how much Contested Legacy could benefit from a more inclusive chronology. And, perhaps more importantly, one also wonders how much the public’s understanding of Russian avant-garde could benefit from art historical scholarship that favors historical continuity over rupture.