European City in a Cultural Upswing: The Art Encounters Biennial in Timișoara

The fifth edition of the Art Encounters Biennial in Timișoara, Romania, took place this year from May 19 to July 16, 2023. Entitled My Rhino is Not a Myth, about forty per cent of the exhibited works were from the region (with more than half of these from Romania) and the remainder from other regions including Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia. The exhibition was staged in historic and contemporary buildings in two urban areas – the city center and the new residential and business district ISHO in north-eastern Timișoara – with eleven venues in total, if one included Mary Dagny Juell’s public space monument and the old tram that ran through the city with Carlos Amorales’ Black Cloud (2007). Swiss-Indian curator Andrian Notz was appointed by the Art Encounters Foundation, and he in turn engaged a team of co-curators – or a curatorial collective as they present themselves – comprising Cristina Bută, Monica Dănilă, Edith Lázár, Ann Mbuti, Cristina Stoenescu and Georgia Țidorescu.(Cristina Bută, conversation with the author, 16 July, 2023)

Carlos Amorales, Black Cloud (2007-ongoing). Photograph by Andrei Infinit and Constantin Duma. Courtesy of Art Encounters Foundation.

While the Biennial has been organized by the Art Encounters Foundation since 2015, the 2023 edition was special, as it coincided with Timișoara’s designation as European Capital of Culture, and thus took place in a lively cultural atmosphere. Along with the Biennial, the visual arts are represented through a comprehensive survey exhibition of modern and contemporary Romanian sculpture – titled after SCULPTURE/SCULPTURE after – at the former military barracks Cazarma U (on view until 30 November 2023) and the exhibition Different Degrees of Freedom, featuring Romanian and other European artists at Kunsthalle Bega.(Curated by Diana Marincu, creative director of Art Encounters Foundation, temporarily replaced by Ami Barak. They jointly curated the 2017 Art Encounters Biennial) In addition, there are solo shows of internationally renowned figures in Romanian art, such as a retrospective of the surrealist Victor Brauner, the drawings of Adrian Ghenie, the star painter who was part of the post-1989 artistic trend dubbed “The Cluj School,” and the largest-ever survey in Romania of Constantin Brâncuși’s sculptures at the National Art Museum of Timișoara (on view until January 28, 2024).

Volume through Layers, curated by Ciprean Mureșan as part of the exhibition after SCULPTURE/SCULPTURE after. Photograph by Sjoukje van der Meulen.

The Art Encounters Biennial 2023 was reviewed in the European press as “more ambitious than ever” and “the most interesting exhibition in Europe this summer.”(Ivana Cholakova, “The Art Encounters Biennial Reimagines Europe From Its East,” June 7, 2023, https://www.frieze.com/article/art-encounters-biennial-timisoara-2023; Niccolo Lucarelli, “La Biennale di Arte di Timișoara,” Art Tribune, July 8, 2023. Reviews appeared in the art press of Austria, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy and the UK, plus minor news items in Mexico and Taiwan. In Romania, according to the Art Encounters Foundation, there were more reviews of the Biennial than in previous editions) The Biennial may not yet appear in the hyped lists of “top biennials,” but judging by this fifth edition, it stands at an interesting and promising crossroads that deserves global attention.(For example, Artnet (top 20) and Art News (top 10) produce such lists) Eastern European biennials tend to be overlooked, even though alternative and engaging biennials have emerged throughout Central and Eastern Europe over the past two decades to advocate and give visibility to local and regional art and cultural infrastructure on the one hand, and to remain in (artistic) dialogue with international art on the other. The Art Encounters Biennial is one of them and also performs this balancing act between local and global art contexts, as described by Nicolas Whybrow in his recent book on contemporary art biennials in Europe (2023):

Although almost all non-Western biennials [Central and Eastern European biennials fit this description too](Whybrow’s geographical framework is Europe, and for the case studies he discusses the Mikser Festival in Belgrade, Serbia) conceptually position themselves as an alternative to the international circuit through some focus on the local, each one attempts to legitimize itself, to some degree, within contemporary art’s global ‘system of validation and hierarchical differentiation.'(Nicolas Whybrow, Contemporary Art Biennials in Europe. The Work of Art in the Complex City (London and New York: Bloomsbury Publishing 2020)

The first Art Encounters catalogue (2015) describes this ambition in a slightly more inspiring tone: “From the onset, Art Encounters aimed to map Romanian art’s place in the wider context of international art and from the perspective of its own evolution.”(Grațiela Benga, Paul Vălean and Sorina Jecza, Art Encounters: Appearance and Essence (Timișoara: Art Encounters Foundation 2015), 4-5) Important within a global context is the critical question raised by this Art Encounters and other biennials in Central and Eastern Europe (Kyiv Biennial, Kaunas Biennial, etc.) about scale: in what format does a biennial still make sense?

Postcolonial approach

The overarching theme of this Art Encounters Biennial is the intersection of art, science and fiction, epitomized by Albrecht Dürer’s famous woodcut of the rhinoceros (1515). In the words of Notz: “Both art and science can be seen as creating fictions about how we understand and see the world, which mutually influence each other, of which Dürer’s rhinoceros is a good example.”(Andrian Notz, conversation with the author, July 16, 2023) Although the woodcut, with some bizarre details, is hardly a scientifically accurate depiction of a rhinoceros, it was nevertheless the best rendering in Europe at the time, which is why it found its way into encyclopaedias and natural history books. Indeed, this rhino is not a myth, but was in fact a real animal sent from India to the king of Portugal and then to the pope in Rome in the sixteenth century – although it never arrived, perishing at sea. Dürer never saw it, but drew it based on a written description and a sketch of the animal. The rhino’s story connects Portuguese colonial history in India to the concept of the Biennial, which develops a postcolonial approach to art and science. Indian artist Sahil Naik deconstructs this colonial history of the Indian rhino in his cabinets and video The Bird, A Bone and Other Witnesses in a Museum Fire (2023) at the National Art Museum of Timișoara, a Habsburg-era Baroque-style palace and a central venue of the Biennial.(All Biennial staff (Gavril Pop, Marius Stan) and curators (Notz, Buta) I spoke to consider this a seminal work) In the Romanian context, the rhinoceros is also evocative of the play Rhinocéros (1959) by Romanian-born French playwright Eugène Ionesco. The play is usually described in terms like “absurdism” and even “Dada,” but it is also a critical allegory of a society in which people gradually succumb to dictatorship, which resonates today in the form of far-right threats and the war in Ukraine.

Sahil Naik, The Bird, A Bone and Other Witnesses in a Museum Fire (2023). Photograph by Andrei Infinit and Constantin Duma. Courtesy of Art Encounters Foundation.

A Dadaist spirit, along with themes of art and science, India, colonial history, and a critical view of the present align with the chief curator’s background, career, and interests. Notz worked for fifteen years as artistic director for the Cabaret Voltaire (2012-2019) and has numerous publications and exhibitions on Dada to his name, including a series of exhibitions on Dada in Romania, recognized by art historian Tom Sandqvist as the real birthplace of Dada.(Tom Sandqvists, Dada East: The Romanians of Cabaret Voltaire (MIT Press, 2006)) Since 2019, Notz has been working at the ETH Zurich AI Center, where his job is to involve artists in AI research and vice versa. His approach to art and science is informed by the historical avant-gardes of the first half of the twentieth century, which Notz says, “faced conditions and challenges similar to those of today: pandemics, rapid technological development and war.”(Adrian Notz, conversation with the author, July 16, 2023) That makes an analogy between art in both periods instructive: “How did artists respond then; how do they respond now?”(Adrian Notz, conversation with the author, July 16, 2023)

Art and science have a strong presence in the core exhibition at the Art Encounters Foundation headquarters, an early twentieth century wool factory building and one of six venues in the otherwise modern ISHO district. On the two floors of classic white exhibition spaces, the themes of art, science and fiction are variously explored in the artworks, often questioning the power inherent in representation: who defines the image, who constructs (art) history? One example is Babylonian Vision (2019) by German-Iraqi Nora Al Badri, a research-based installation with postcolonial critique. Using a database obtained by scouring the internet for images of artefacts from Mesopotamian, Neo-Sumerian and Assyrian cultures held by major Western museums, Al Badri subjected them to AI software with machine learning to generate a new collection of images. New technology as a means of liberation and emancipation, if not digital reappropriation. Another work that shakes up and questions the meaning of the artistic image is a large-scale photograph created by the Slovenian art group IRWIN of the Macedonian Orthodox bishop Metodij Zlatanov, holding Duchamp’s version of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa with the ‘blasphemous’ text L.H.O.O.Q. in his hands, along with a video showing the same bishop praying for Dada founder Hugo Ball in a tribute to his sound poems. This questioning of the image and creative cross-pollination with science takes place in many other contemporary and historical artworks, such as by Constantin Flondor (of the Romanian avant-garde Sigma Group)(The Sigma Group, founded in 1969 in Romania and active until 1978, is a (neo-) avant-garde group known for integrating science and research into their artistic practice. Constantin Flondor is one of the group’s founders), Christodoulous Panayitou, and Liat Grayver and Marcus Nebe.

IRWIN, What is Art: DA + DA (2010). Bishop Metodij Zlatanov of the Macedonian Orthodox Church holding Marcel Duchamp’s ‘L.H.O.O.Q’ (1919-1930). Photograph by Andrei Infinit and Constantin Duma. Courtesy of Art Encounters Foundation.

Promoting Romanian art

Joining Ann Mbuti, a Zurich-based writer and critic with a postcolonial focus, are five curators from Romania, some with significant international experience and training (Edith Lázár, Cristina Bută.(Ann Mbuti recently published the book Black Artists Now: von El Anatsui bis Kara Walker (Munich, C.H. Beck Verlag, 2022) (in German)) They all have varying degrees of experience, working for galleries in Bucharest (e.g. Sector 1 Gallery; Posibilă Gallery), experimental art spaces in Cluj (Aici Acolo, Superliquidato), and a cultural association in Timișoara (Contrasens Cultural Association). They met in 2020 at the Autumn School of Curating in Cluj on the theme “The New Now,” led by Notz and organized by the European Center for Contemporary Art (ECCA) and the Art Encounters Foundation. They are clearly well connected to the Romanian art scene and were crucial in achieving one of the Biennial’s goals of promoting Romanian art, especially by younger generations of artists. In recent decades, Romanian artists have gained international acclaim, such as Ciprian Mureşan and Adrian Ghenie, as well as artists of older generations, such as Ana Lupaș and Geta Brătescu, but younger artists with interesting or promising work are often hardly known outside Romania.

Thirteen young Romanian artists were commissioned to make new work for the Biennial. One of them is Sebastian Moldovan (1982), who made a site-specific installation in the 1927 tram depot, baptised STPT Multiplexity, where old, run-down trams are still stored, both inside the sheds and in the courtyard overgrown with plants. A site from bygone times that captures the imagination, the depo was transformed into a dystopic place by Moldovan and two artists he invited as collaborators on this installation, Albert Kaan (1993) and Lucia Ghecu (1990). In the vast space of the depot’s sheds, one entered a fictional world, with a fake rock-making workshop, ‘abandoned’ drawings on the wall and mini-screen video monitors in unexpected places (under a tram, on the high ceiling, a hole in the wall), showing a man interacting with the space in various eerie ways, evoking danger and the desire to come to the rescue. Other artists contributed to this venue, where together they approached art and science as science fiction: Janiv Oron created sound art using a technique called Electronic Voice Phenomena (EVP) that transformed a tram interior into a haunted space with ghostly visitors summoned from the past, while Cristian Răduță’s apocalyptic, surrealist creatures occupied another tram close to the venue’s entrance.

Sebastian Moldovan, Post-World Undercover Guerilla Fake Rock Manufacturing (2023). Photograph by Andrei Infinit and Constantin Duma. Courtesy of Art Encounters Foundation.

Janiv Oron, Visitors (2020). Photograph by Sjoukje van der Meulen.

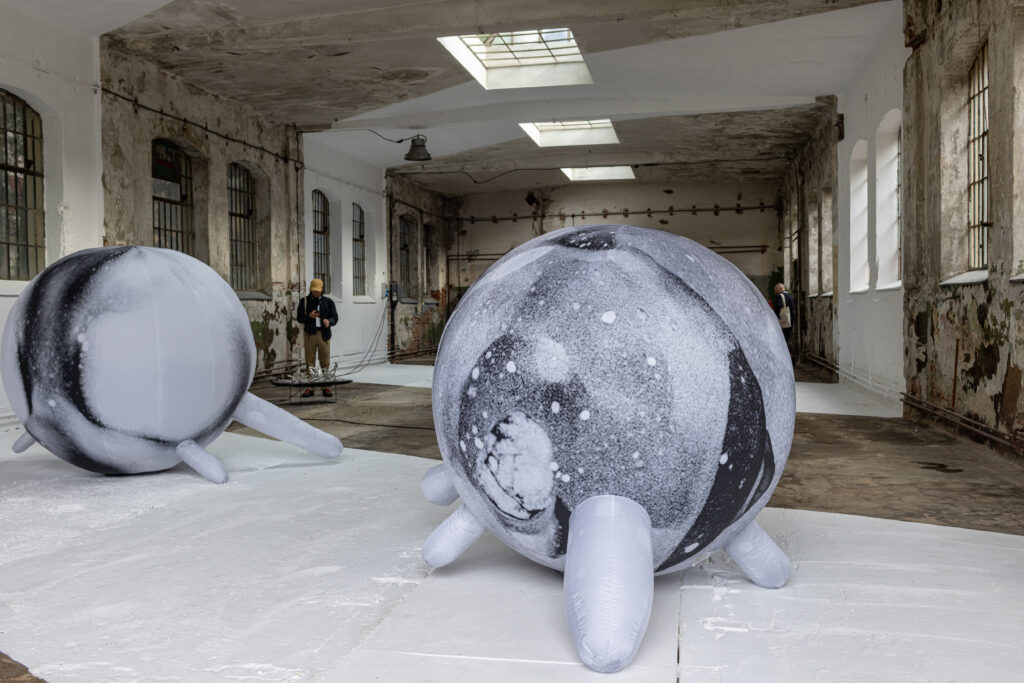

In another shed, Anetta Mona Chișa’s post-nuclear elements were blown up into sculptures scattered across the floor. The contagious creativity at STPT Multiplexity was a highlight of the Biennial.(There are plans to transform the green and spacious site of the old tram depot into a centre for art, technology and experimentation. The current exhibition seems to indicate that the genius loci of this disused site is just the right place for experimental art and creativity) Newly produced work by Romanian artists could be found at other exhibition venues in the ISHO district, but in the more predictable sense of art at the intersection of science, such as Floriama Cândea’s interactive installation Obiect Somatizant #2 (2022) in which the artist, in dialogue with biomedical engineering, uses AI sensors to make your pulse tangible and visible in the responsive fluid in the installation’s interconnected test tubes.

Anetta Mona Chișa, The Children (in Ununennium’s dream) (2023). Photograph by Andrei Infinit and Constantin Duma. Courtesy of Art Encounters Foundation.

Floriama Cândea, Obiect Somatizant #2 (2022). Photograph by Andrei Infinit and Constantin Duma. Courtesy of Art Encounters Foundation.

Multicultural diversity

Timișoara, the provincial capital of the Banat region and the city where the Romanian Revolution began in 1989, takes pride in its multicultural diversity, which has evolved from its intricate history. A succession of foreign and domestic powers, from the Ottomans in the sixteenth century, via the Habsburg monarchy in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and the short-lived Kingdom of Romania between the two world wars, to Nicolae Ceausescu’s post-war communist rule until 1989 and the transition to a democracy and market-oriented system, resulted in a very diverse population: Romanians, Hungarians, Germans, Serbs, Bulgarians, Italians and Greeks all living together peacefully. The city also fosters a culture of religious tolerance, with (Orthodox) Christian, Jewish and Muslim religious traditions. This historical diversity and culture of tolerance is also why Timișoara, was a good candidate for European Capital of Culture, as these are major values shared and promoted by the EU.(Of course, the composition of the population is complex: many citizens are born of mixed marriages and have multiple cultural backgrounds. In recent decades, South and East Asians are settling in Romania as well)

And yet, according to Notz, “connections to artistic scenes in neighboring countries are remarkably weak, in both directions.”(Adrian Notz, conversation with the author, July 16, 2023) This is especially true for Serbia and, to a lesser extent, Hungary, even though Timișoara is closer to Budapest and Belgrade than to the national capital Bucharest. This might be explained by Romania’s orientation toward the West since the transition from a socialist to a capitalist system, or by unresolved obstacles in the present, such as the relationship between Serbia and the EU, the right wing political climate in Hungary, or the fact that Romania is not a member of Schengen. (Although Romania and Bulgaria meet all conditions, they are still not admitted to Schengen as of August 2023. Austria and my country, the Netherlands (mainly for reasons related to migration that tell more about Dutch politics than about Romania), have blocked these countries accession to the Schengen area once again in December 2022. According to the EU Parliament, however, they should be part of Schengen by the end of 2023. See: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20230707IPR02431/) Whatever the reason might be, this Biennial seeks to open interregional relations in the artistic field by inviting artists from all neighbouring countries: Bulgaria, Hungary, Serbia, Moldova and Ukraine. Most of these works, such as a ‘shock’ installation by Dimitov Solakov (BG), charcoal drawings by Nataša Kokić (RS), a sci-fi painting by Hortensia Mi Kafchin (UA) and sculptures by Anna Godzina (MD) and Kata Tranker (HU) were on display at venues in the city center such as the Garrison, a former military building whose vaulted ground floor was used to display sculptures, and the National Museum of Banat, popularly called ‘The Castle,’ which was reopened for the Biennial after fifteen years.(The name relates to its medieval origins, the Huniade castle, which is in fact the oldest building in Timișoara (1308-15)) Russian Rocket (2022) by Ukrainian artist Zhanna Kadyrova was particularly poignant: an image of a rocket at full speed on its way to its target, stickered on a window through which you look across a historic square, bringing the war closer.(Russian Rocket (2022) by Zhanna Kadyrova consists of two related works with the same title: a video in which the rocket soars through the Ukrainian landscape, and stickers that can be affixed to windows and other places)

Zhanna Kadyrova, Russian Rocket (2022). Photograph by Adrian Câtu. Courtesy of Art Encounters Foundation.

Global dialogue

Each exhibition venue at the Biennial had a thematic focus (such as ‘representation’ at the Art Encounters Foundation, or ‘Science Fiction’ at STPT Multiplexity) within the overarching concept of art and science. A number of topical sub-threads also run through the venues, such as diversity and inclusion, and the relationship of humans to nature in the Anthropocene, a postcolonial topic certainly related to science. International artists in the Biennial thus had plenty of contact zones for dialogue with the regional and local art scenes. Each venue, both in the ISHO district and in the city center, showed work by at least one artist from another part of the world who is active and well-known on the global art circuit – Asia, especially India, was well represented, but there were also artists from South America and Africa.

At the Faber Cultural Centre, where language and code were a theme, Alicja Kwade’s installation Medium Median (Homo-Measura) (2016), consisting of connected iPhones dangling from the ceiling, offers a quasi scientific, philosophical reflection on humanity’s position in the universe in the digital age. In Pteridophilia (2016-ongoing), a video installation by Hong Kongnese artist Zheng Bo at the Garrison, a queer man has an erotic encounter with plants. This installation has been shown before, for instance at Manifesta 13, but in Romania it caused a controversy in the press and even a lawsuit for pornography filed by a Christian organization.(See Vlad Marko Tollea’s article, published online in Romanian and English: “The exhibition that caused a scandal in Timișoara,” Libertatea, August 15, 2023, https://www.libertatea.ro/stiri/expozitia-care-a-starnit-un-scandal-in-timisoara-o-asociatie-crestina-i-a-dat-in-judecata-pe-organizatori-acte-sexuale-explicite-cu-plantele-si-aluzii-la-relatii-intre-persoane-de-acelasi-s-4634133) In the context of the Art Encounters Biennial, Zheng’s scientifically informed artistic ecopractice was neatly in dialogue with the artworks around him, equally committed to inclusion and care for our planet (Ioana Cîrlig, etc.). The most conspicuous international artist was Mexican artist Carlos Amorales. In addition to his post-colonial video The Eye-Me-Not (2015) about an Inuit seal hunter whose father was killed by European whalers, Amorales made his ‘signature’ black paper moths swarm in one of the old trams, which was allowed to run again through Timișoara during the Biennial – as if it were a nostalgic “time shelter” straight out of the award-winning novel by Bulgarian writer Georgi Gospodinov.(Georgi Gospodinov, Time Shelter, translated by Angela Rodel (London: Weidefeld and Nicolson, 2022))

Biennial culture

“To Biennial or not to Biennial, that is the question,” as Maria Hlavajova put it in 2009.(Quoted in Whybrow, Contemporary Art Biennials in Europe, 6) With its substantial but manageable scale, this Art Encounters Biennial demonstrates that an overarching aim is not to house as many artworks as possible – as often seems to be the case with large scale, high-profile biennials that follow the ‘invisible hand’ of the “glocal economy”– but can have meaning that does not get snowed under by the scale.(Thierry de Duve, “The Global and the Singuniversal: Reflections on Art and Culture in the Global World,” in The Art Biennal as a Global Phenomenon: Strategies in Neo-Political Times, Open 16, ed. by J. Seijdel (Amsterdam: NAi Publishers/SKOR), 49) After visiting all the venues, one message lingers that is relevant to the current era of AI and the climate crisis: not unbridled advancement of technology and science, but a collaborative and fair science working with art for its social function, the pursuit of a livable world for humans and the environment – a message that sounded idealistic in the past but is rather urgent today.

Curatorial team Adrian Notz, Cristina Bută, Monica Dănilă, Edith Lázár, Ann Mbuti, Cristina Stoenescu, and Georgia Țidorescu. Photograph by Andrei Infinit and Constantin Duma. Courtesy of Art Encounters Foundation.

Another aspect of the smaller or medium-size biennial that is important for its credibility if it is to generate meaning beyond cultural tourism, is its “situatedness” in the local community. The spirit of collaboration in this Biennial was impressive, not only between the curators and the artists, but the entire local art scene of Timisoara and beyond: art collectors (in the first place Ovidiu Șandor, President and co-founder of the Art Encounters Foundation), gallerists (such as Sorina Jecza, co-founder of the Art Encounters and Triade foundations, who added art historical depth by the Romanian sculpture exhibition supported by the European Capital of Culture),(The Triade Foundation, in collaboration with Attila Kim & Architects, joined forces with Sorina Jecza to curate and oversee a series of exhibitions titled “after SCULPTURE, SCULPTURE after” focusing on contemporary Romanian sculpture. Jecza invited esteemed curators and art historians Ioana Vlasiu and Alina Șerban as curators, along with artist Ciprian Mureşan. These exhibitions are held together by Rosalind Krauss’ idea of “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” exploring the temporal and spatial dimensions of sculpture in all its various modern and contemporary manifestations within a Romanian context) and local artist collectives and spaces (Balamuc, Avantpost). Still, there are a few critical points: first, the choice of a non-hierarchical and collaborative curatorial model (a novelty in the rather hierarchical Romanian art context) was somewhat compromised by the fact that the chief curator was a middle-aged man assisted by a team of six young women – not exactly a paragon of gender equality. The curatorial team worked well together, as seen in the venues, where no one curator seems to have the upper hand, but from a feminist perspective, the non-hierarchical approach still raises questions. For example, were they also paid equally? The potential conflicts of interest pertaining to the President, who is involved in real estate, are also clearly discernible. As the main investor in the ISHO development project, he benefits from the cultural capital that is being accumulated there as well, regardless of the Biennial’s overarching mission, which is unequivocally centered on the promotion of Romanian art and cultural infrastructure. At the same time, one needs to acknowledge the pivotal and constructive role that private collectors as Sandor play in advancing modern and contemporary art within the Eastern European context.(See: Gábor Ébli, “Collecting Contemporary Art in Eastern Europe, II: Do Institutionalised Private Collections Measure up with Museums?” Revista ARTA, February 22, 2016, https://revistaarta.ro/en/collecting-2/)

These issues notwithstanding, Timișoara certainly has momentum in terms of art and culture, and hopefully this can be maintained and continued, not only in a cultural sense, but also in a material sense by, for example, securing the partially renovated buildings such as the Tram Depot, the Garrison and Cazarma U, that have been repurposed for the arts as part of the Biennial and European Capital of Culture 2023.