Utopia in Ukraine? Members of Concrete Dates Collective Reflect on In Edenia, A City of the Future and the Role of Utopia in Artistic Work

The art exhibition In Edenia, a City of the Future (June 8–July 9, 2017), co-organized by artist Yevgeniy Fiks and curator Larissa Babij, was inspired by the novella of the same title by Yiddish author and publisher Kalman Zingman. The story, written in 1918, takes place in a utopian future version of the real eastern Ukrainian city of Kharkiv, which is serviced by “aerotrains” and fountains that keep the temperature at a comfortable level year round. In Zingman’s world, ethnic communities, including Jews and Ukrainians, live side-by-side in peace and harmony, and residents consider war a thing of the past. Edenia’s art museum, although described in only one sentence, remains a sanctuary for individual contemplation of works of high culture and plays a central role in the narrative. For Babij, Zingman “maintains a separation between the realms of everyday activity, where technological advancements have increased the comfort and ease of residents’ lives, and the sphere of culture. It’s interesting to contrast this vision with that of the early Soviet avant-garde, which envisioned art and its formal possibilities as a means to transform out-dated ways of living, to shape and prepare society for new forms of organization, often through a violent break with and obliteration of past cultural traditions.” (https://www.calvertjournal.com/articles/show/8498/edenia-lost-yiddish-utopia-ukraine-afterlife-modern-day-kharkiv)

Nearly 100 years after the book’s publication, the curators invited an international group of contemporary artists—including Babi Badalov (France/Azerbaijan), Ruth Jenrbekova and Maria Vilkovisky (Kazakhstan), Aikaterini Gegisian (Greece/Armenia), Haim Sokol (Russia/Israel) and Nikita Kadan (Ukraine)—to read it for themselves then create an artwork as if from the art museum of Zingman’s imaginary city of Edenia. The resulting works, which raised many complex questions about Ukraine’s multicultural history and the legacy of the Soviet project, were shown in Kharkiv at the Yermilov Center, not far from the Ukrainian territories beleaguered by war since 2014. The idea behind the show was to turn the visitors’ attention back to an earlier period of violent political and social conflict and its hopes for a better future. The curators urged “visitors to think critically about the appeal and comfort of a utopian dream, while simultaneously remembering past actions taken in the name of making an ideal image of society a reality. How many of these dreams and arguments are we still repeating today?”(http://yermilovcentre.org/2017/05/29/in-edenia-a-city-of-the-future/)

The Kyiv-based Concrete Dates Collective (CDC), formed in 2015 as an experiment in collective artistic activity, was among the participating artists. They showed a series of three paintings, each depicting a scene from idealized Jewish village life. The paintings were accompanied by an audio narration exposing the elaborate labor process behind each painting and discussing the relationships between the people involved in its production, sale, and enjoyment. Not long after the exhibition, the collective stopped working together due to long-standing internal conflicts. Below is a conversation with some members of CDC—Pavel Khailo, Yegor Antsygin, Olga Kubli, Anna Shcherbyna—who reflect on utopia, the exhibition, and their failure to keep working collectively.

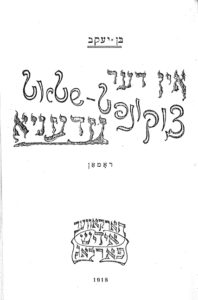

Title page, Kalman Zingman, “In der tsukunft shtot edenia” [In Edenia, a City of the Future], Kharkiv, 1918.

So in the case of Zingman, it seems that the Kharkiv he described was not a utopia in his eyes. Sure, it’s a personal and in many ways naive text, written on a wave of revolutionary enthusiasm at a moment when the war was still raging and the Bolsheviks’ power was not assured, amidst news of ongoing anti-Jewish pogroms. The author was twenty-nine years old, when he wrote this text describing a completely different ideal world, but one that would be attainable in twenty-five years. In other words, he was practically planning to live there himself. We call unsuccessful projects of the past “utopian.” But by doing so, don’t we exclude from the conversation the very possibility of effecting change?

Yegor Antsygin: In many ways, the situations I see around me today demonstrate that utopia is impossible. There is certainly an attitude toward utopia as a weak, nearly unrealizable future that by tacit agreement cannot come to be; but it still contains something real that makes it possible for it to exist in the field of art and interpretation.

Olga Kubli: For me, two notions of utopia exist: one is imaginary, the other is real. The imaginary kind helps one learn or understand a lot, and of course it’s interesting to analyze. But the realization of utopia scares me, as it does not account for context, preconditions, or the past and the present. And the only place where I think one can (and ought to?) go from imaginary to real utopia is in the field of art (here CDC’s experience comes in), where the activities most fundamental to life are least affected. So the exhibition In Edenia, a City of the Future was quite interesting—as it was the realization of something imagined in a safe space. I had envisioned it as an attempt to realize a utopian project within an exhibition space, as a sort of metawork involving the works of participants. But that’s not what I saw. Instead, there were separate works without a binding substance, and there was no unified program that one could test for “utopianness.” So one might say that the very idea of making a utopia-themed exhibition is utopian.

PK: I still think it’s important to clarify that the exhibition was about utopia only to the extent that we consider Zingman’s novella a utopia. And it’s significant that the central work in the exhibition space was Babi Badalov’s mural NO(W) FUTURE. The play on words directly points to the vacillation between acknowledging the absence of the future and demanding that it happen now.

Babi Badalov, “NO(W) FUTURE,” 2017, mural. Photo by Sergey Solonskij.

Anna Shcherbyna: Olga, you just said that “the very idea of making a utopia-themed exhibition is utopian.” I think this exhibition was an endless inquiry, an attempt to grab on to something. It’s been 100 years since this novella was written, and we still have no favorable program. We (artists, curators, the public) have admitted our own impotence and are reflecting on it.

As we were preparing for our contribution to the exhibition, I imagined the art museum of Edenia. And I think that our work—without the audio component—could certainly have graced the walls of that museum. An ideal society has no need for a critical viewpoint; it only has room for art that glorifies the beautiful world. It needs the kind of art that moves the spirit and sends a warm feeling through the body with just one look.

And, believe it or not, that’s the kind of art we’re taught to make in the National Academy of Art & Architecture in Kyiv. In the context of Ukraine this is partly the consequence of countless years spent following the official Socialist Realist canon, which was built on maintaining and singing the praises of the ideal Real. As if through some kind of magic by depicting a person as an ideal member of society, he or she would become it. Or at least (such was the hope) nobody would notice the discrepancy with the real Real. And whoever noticed it was quickly singled out as having a depraved mind. But it’s not worth blaming everything on the Soviet past. Today, Ukraine has a lot of trouble admitting to anything: weakness, mistakes, crimes. It seems a lot simpler to cover a hole in the wall with a picture in an ostentatious frame (to hide the eyesore), than to embark on a full-scale renovation. So what, if there’s a draft coming through the window? It’s nothing, it won’t blow the roof off. We’ve always managed somehow.

YA: Since Anna has mentioned our work, I like how the “trade” of several members of our group was incorporated into our collective’s work, how this work resonated in the exhibition as a whole, and how our “domestic factor” became “reality” in an exhibition about utopia.(The audio component of Three Paintings in the Exhibition reveals that the paintings on display were painted by two members of the collective to be sold in a Brooklyn gallery under the name of a different artist.)

Concrete Dates Collective, “Three Paintings in the Exhibition,” 2017, paintings and audio. Photo by Sergey Solonskij.

Looking back on all the artworks in the exhibition, I would say that the content was quite complex. Take, for example, Sasha Dedos’s hammer Friday Before the Last Saturday (2017) and the Creolex Centre’s sci-fi film Transoxiana: A Tour for Newcomers (2017).(Creolex Centre is Ruthie Jenrbekova and Maria Vilkovisky.) The first work I see as a minimalist object, a self-referential readymade like a “serpent biting its own tail,” which produces new meanings in relation to Zingman’s story and the time when the novella was written. The second work, which takes the format of a television report, is the fictitious story of the establishment of a federation of united tribes with graphics and tables and an abundance of information that almost repels the viewer with its demands on their perceptive apparatus. But again, if one keeps in mind the work’s main idea—the organization of a new utopian city of the future – the message becomes clearer. These works offer a multitude of ideas and interpretations, and this is important—to make exhibitions that are not straightforward or simple. To judge this exhibition according to “how utopian it is” is as ridiculous as judging a conceptual artwork according to its financial profitability.

Sasha Dedos, “Friday Before the Last Saturday,” 2017, found hammer and nail. Photo by Sergey Solonskij.

PK: Yet why was it important for us to talk about utopia at all and to talk about it now? Of course there’s the political context and a certain public eagerness to forget the past and zoom into the future. But why was this important to us as a collective?

AS: Now is simply the time to talk about utopia. Incomprehensibility and excesses, a complete lack of certainty in tomorrow, disorientation—these all frustrate me. Utopia is necessary to keep from going crazy from indeterminacy. Utopia lets us see how far we are from it and serves as a point toward which to orient our actions. Or it’s a sign to change direction if that utopia is no longer relevant. Utopia as such can be unrealistic. It’s not creating utopian scenarios that’s naive, but trying to create utopia according to these scenarios. Besides, there should be a vision of the end result and a plan for its realization. There should be an idea, an image of what is desired, otherwise any action will aim at nowhere.

Our collective was also a utopian project. It arose on a wave of general enthusiasm and faith in collectivity. We saw ourselves as a structure whose work comes out of shared interests and an impulse from within the collective. It was like that in the beginning. In the process we encountered a number of difficulties related to things like personal/collective responsibility, power, motivation, or lack thereof. The difficulties got the better of us and we didn’t become a collective. But we tried.

OK: After thinking and thinking and thinking, I decided that it would be most honest to admit that I’m interested in talking about utopia now because of my age! I’ve simply started noticing that everything going on around me is terribly dissatisfying: how people relate to one another, the educational process, the economic and political situation. What I dislike most is how it is all in essence utopian (in the sense of the impossibility of benefitting all parties involved). And you start talking only when you’re in the midst of a crisis. Before — you don’t see it; after—you’ve accepted it.

PK: I’m also thinking of the connection between our work and the work of being an artist in Ukraine in general. If “utopia” is “no place,” then one always feels out of place making art in Ukraine and wants some kind of “normal” process—with critics, institutional support, transparency. But it seems like that process is diminishing everywhere. So we may be ahead of the game, but that doesn’t make it any easier.

OK: Yes, we need utopias, not as ideals to aspire to, but on the contrary—to understand which direction(s) we don’t need to go. In the same way that the capacity for abstract thinking helps people survive, in this case abstract potentialities die out when faced with actual actions.

YA: For an artist, the fields of art and existence are tightly bound. It is a contradiction to engage in an occupation that cannot support you financially, and yet claim that you are an artist by profession. Questions arise: Are you good at what you do? Can you even call the profession of “artist” a profession? How often does it justify this status? These questions encapsulate the pain and suffering of those in this field, when even the most serious art institutions do not ensure artists financial independence. Finally, working as an artist and trying to support yourself with this work is pretty utopian.

AS: In art, as in public and private life, you continually run into the gap between an idea and its incarnation. The gap appears and becomes inevitable when reality becomes inaccessible. In this situation of chronic instability, I desperately try not to expect anything, to turn off my ability to project. And that is when the Ideal intrudes upon my consciousness. It appears in the image of a dream, seductive and audacious. I imagine how I’d like to redecorate my room; the image in my mind is quite inspiring. But in reality I don’t have the means: I manage to paint three walls, meanwhile splattering the ceiling and floor. It would be great if everyone received an unconditional basic income, but somehow that’s not happening.

But sometimes one’s will takes the place of the dream. For example, I decided that I want to write this text on utopia. It doesn’t flow out like a river or magically appear on the screen. Writing it takes effort, and in this case, not mine alone. We have to get together, decide what to write about and how, approve the decision, and then everyone who agrees to these conditions can get to work on the text. We approached each of our works as a collective from this principle. These principles weren’t written down, but discussed each time.

On the one hand, the absence of a written document formalizing what to do and how to do it let us be open and sensitive to the changing needs of the participants. Every time we could change the terms and, thus, adapt to the moment. On the other hand, the invisibility of our rules was disorienting. We should have set down the rules and made a charter! It would have given shape to our conceit, manifested the idea of an artists’ collective, and at the same time would have served as a point of reference, something to consult in conflict situations. Though I’m not sure that would have saved us. I’m not sure that a precisely framed conceit guarantees success in action.