The Agency of Lack: Mikhail Tolmachev on His Installation at the Moscow Gulag Museum

Mikhail Tolmachev was born in Moscow and lives in Leipzig. His work touches on questions of institutional memory and display, documentary history, and media archeology. Recent shows have included Sources Go Dark (Futura Center for Contemporary Art, Prague 2015); Beyond Visual Range (Armed Forces Museum, Moscow 2014); IK-00 The Spaces of Confinement, Casa dei Tre Oci, Venice, 2014; SLON (V-A-C Foundation, Palazzo Zattere, Venice, 2017).

Sven Spieker: In 2016 you presented an exhibition at the State Museum of Gulag History in Moscow that deals with materials from the museum’s archive, related to the Stalinist labor camp on the island of Solovki in the White Sea.

Mikhail Tolmachev: Yes, I worked with a photo album that is part of the museum’s collection, and it’s from one of the early Stalinist labor camps, Solovki. The camp was established in 1923, and was in operation until 1937, then it was reorganized in to a prison that functioned till 1939. Since 1919 several forced labor camps were founded in that region (Arkhangelskaya oblast’). In my project Pact Of Silence at the Gulag Museum I became interested in the medium of the photographic album as a representation of history, how the history of the Soviet terror is represented through this medium, and what kind of traces that history may have left in contemporary society.

SS: Can you say a few words about what this album looks like? What do the photos show, and why was this album created in the first place?

SS: Can you say a few words about what this album looks like? What do the photos show, and why was this album created in the first place?

MT: The album is one of three photographic albums from this island that are known today. The one on display at the Gulag Museum was made for inside use. So this album was never supposed to leave the camp’s headquarters. Inside the album you can find a lot of images that look more like private photographs of the NKVD officers than like the kind of propaganda images that are usually made in such places. The album consists of about 300 images, and most of them represent the economic use of the camp. For example, how labor can be used for a production of food, fishing, or the making of bricks for sale, and also leather for production or pottery. The camp was inside of a monastery, so it appropriated many of the manufactures that had been established much earlier by monks.

SS: The monastery was no longer functioning at that time?

SS: The monastery was no longer functioning at that time?

MT: No, the monastery was functioning only until 1920, before the Bolsheviks came, and plundered it. At that point everything was expropriated, and the monastery started to be used as a prison. In 1923 it became a real camp, part of GPU, the Soviet secret police. The album’s second part, for me, is more interesting because it contains private photographs taken by officers who were working in the camp at the time. These officers, who were members of a special department and did not belong to the Red Army, apparently had access to the photographic laboratory that was on the island, and they could take photographs whenever they wanted: skiing in winter, going hunting, going swimming in the summer, or just posing at work.

SS: Do you know how the album ended up at the Gulag Museum?

MT: The album was sold to the museum in 2014, coming from a private family archive. The lady who sold it told the museum staff said that the album came from her husband’s family, but that’s questionable. This was the only information provided to museum visitors once the album came to be exhibited on its premises.

SS: Evidently the museum made no special efforts to research the album’s history. Did you see your role as someone who would fill these gaps in the knowledge about the album, and maybe more generally speaking about this particular camp?

MT: Yes. I did several interviews with the seller, and she told me her story. She told me that the photo album was not part of her family, but that family friends had given the album to her family because their son was an alcoholic. I then also I traveled to the islands and made several interviews with a local historian who has studied the history of the Gulag on the island since the early 1980s, and who has a deep understanding of what’s happening today with this history. This historian taught me a lot: she helped me understand where I stand as an artist, from what position I can speak when working with this album, etc. I figured out that the only thing that in this very moment makes sense to tell of this album is our lack of knowledge about it, because these are all images that do not exist in our collective consciousness. We can see that these are old photographs, but beyond that you can’t say who the people in the photos are. And while you can say something about the uniforms, you cannot say anything about the events, or the reason why this or that photograph was taken and preserved in the album. Very little in these images can help you answer the question as to where they might be located in history.

SS: You felt that the way the Gulag museum was showing the album–in a glass cage, and opened on one page–was not suitable for showing this multiple lack of knowledge?

MT: No, that’s the worst thing you can do, opening it on a specific page. During my research for this project, I became interested in Canadian historian of photography Martha Langford. One of her main points for understanding a photographic album is in her emphasis not on visuality but in oral tradition: the album needs to be enabled to tell its story, because normally when you look at an album you have somebody who shows you the images and who helps you get inside its story.

SS: What did you do to activate this hidden story?

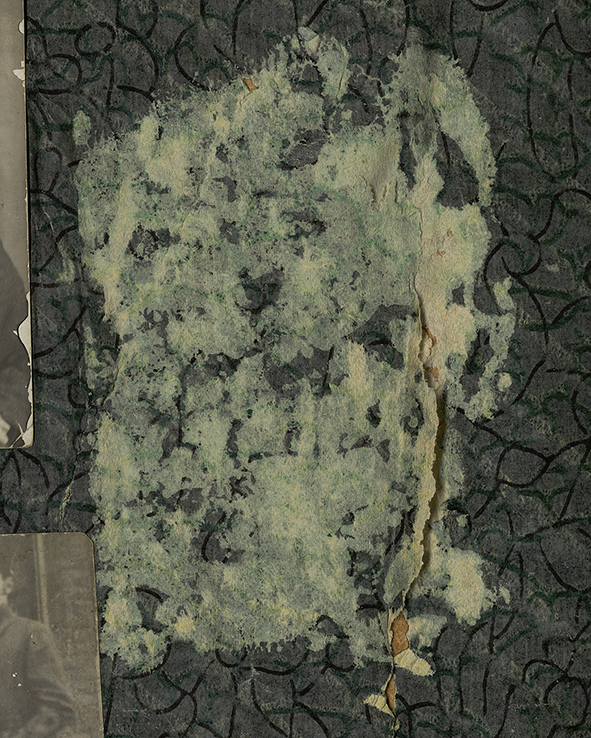

MT: In the album there are twenty-two photographs that had been torn out for some reason. For example, there were pages with a photograph of a young woman with children, and on these same pages a lot of photos had been ripped out. Or, another example, on a group portrait with cutout on the side you can see the shadow of a person who had been there, but who was not supposed to be in the picture for some reason. Why did this happen? To represent these blind pages and cut outs–the gaps in our knowledge–I used one-to-one reproductions of the places in the album where pictures were torn. In other words, I showed empty slots as photographs of absent photographs. In this way I created an installation of images, but not of the images that still exist in the album today, but rather of those images that are absent from it because they had been torn out. It’s a bit like in forensics when you create images of a crime site. I asked myself: How does absence affect memory and collective consciousness? I tried to make myself an accomplice of this absence.

MT: In the album there are twenty-two photographs that had been torn out for some reason. For example, there were pages with a photograph of a young woman with children, and on these same pages a lot of photos had been ripped out. Or, another example, on a group portrait with cutout on the side you can see the shadow of a person who had been there, but who was not supposed to be in the picture for some reason. Why did this happen? To represent these blind pages and cut outs–the gaps in our knowledge–I used one-to-one reproductions of the places in the album where pictures were torn. In other words, I showed empty slots as photographs of absent photographs. In this way I created an installation of images, but not of the images that still exist in the album today, but rather of those images that are absent from it because they had been torn out. It’s a bit like in forensics when you create images of a crime site. I asked myself: How does absence affect memory and collective consciousness? I tried to make myself an accomplice of this absence.

SS: Was there anything else in the installation?

MT: Yes, I added a multi-channel sound installation to the photographs’ display, using material from several interviews I had done with people who are connected to the album’s story, such as the woman who sold it to the museum; a representative of the Gulag Museum, the director of the museum’s archives, and others. My idea was that the images of missing images, on the one hand, and the interviews, on the other, would correspond. Some people in these interviews try to imagine what had been there in the places where images were missing. I also added my own voice as the voice of somebody who looks at the images and tries to understand them without knowing anything about them.

SS: But you did not use the actual voices of the people you interviewed; you had their words spoken by actors. Why?

MT: Because I wanted to move the installation’s focus to an abstract level. That’s also why I used only young voices, to de-localize things further. The voices were not locatable in their age. It was my way of pointing to the lack of knowledge we spoke of before, and to give that lack agency, to see the unknown not as an object, but as a subject.

SS: You use (younger) actors to substitute the speakers in the original recordings in order to dispel the illusion of immediacy, and to prevent the audience from identifying with the documents they encounter. In this way, both the photographs and the album are perceived, precisely, as documents. Would you agree?

MT: That makes sense. I was never interested in representing personal stories. For me, the album is not in the installation. It exists only in the viewer’s perception as a mixture of the voices and the images.

SS: What is specific to your work as an artist as opposed to, say, the work of a historian?

MT: The endpoint for me is the problem of representation and the way a historical event is represented through museum displays, and the politics of such display. I want to look beyond the hierarchical order established between fact and fiction.

SS: This is not the first time that you’ve worked with a museum. When I first met you, you had just opened your installation at the Central Museum of the Armed Forces in Moscow. There, too, you made part of the exhibit invisible, or to be more precise, you gave visitors a sense of what they could not see.

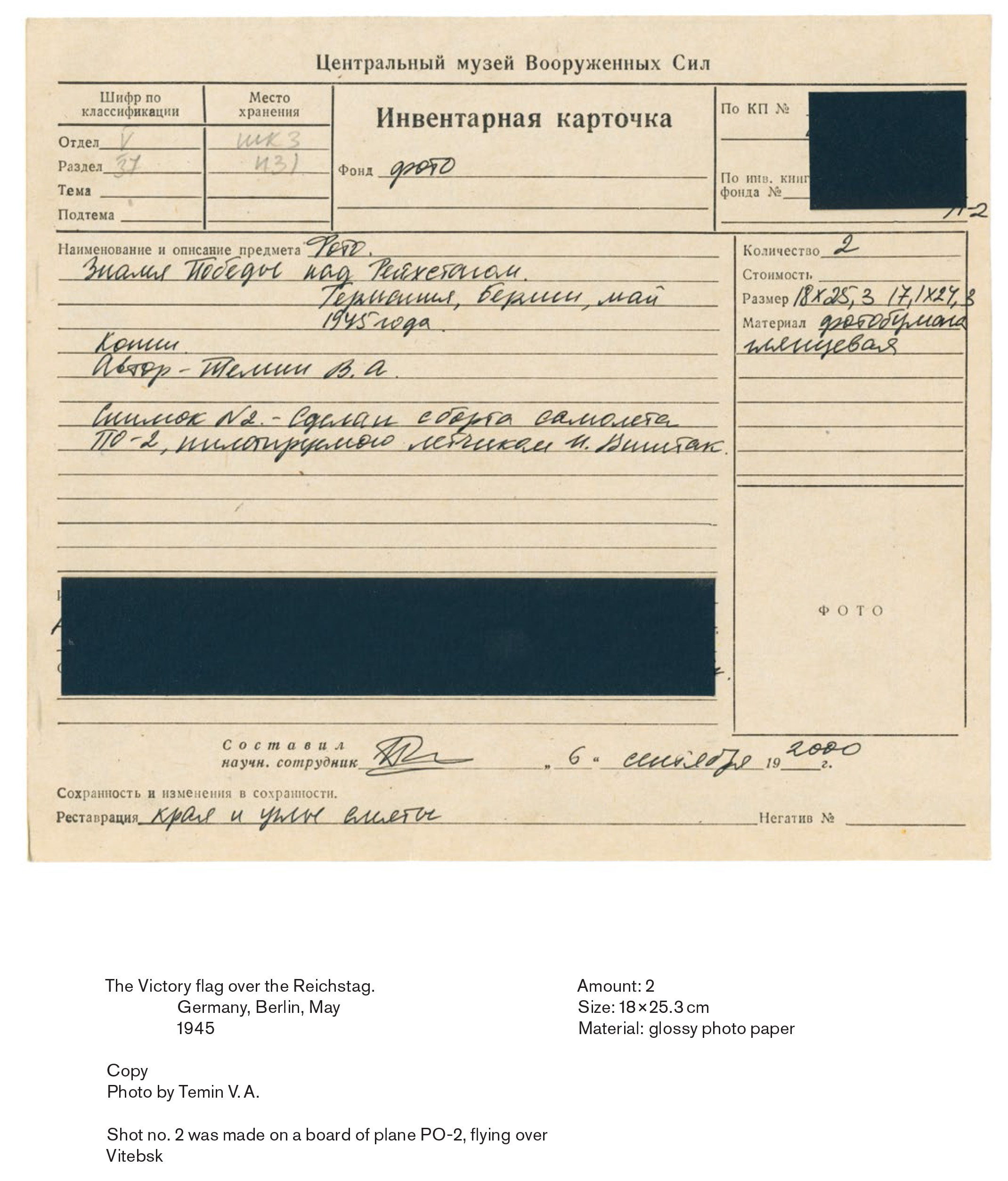

MT: Yes. One of my interventions in the Museum of the Armed Forces took place in the so-called Hall of Victory of the Second World War. It’s is the main hall of the building, right in the middle. Everything in this hall glorifies victory, it is more a monument than a museum, without any room for the reflection. There I did an installation with material from the museum’s photo archives. But my idea was to do an installation not with the photos, but with their archival inventory cards. What I found so interesting about these cards was the fact that they contained no reproductions of the images they inventorized. There was only the textual explanation of what was shown on the (absent) images. The text appeals to your collective visual memory because you have to imagine the images of war that we all have in our heads. Think of the famous (restaged) 1945 photograph of the Red Flag on the Reichstag. So I didn’t show that image (which was in the archives), but instead I showed its card with the photo’s verbal description. I took thirty six such cards that told the story of the Second World War, from the beginning to its last days.

MT: Yes. One of my interventions in the Museum of the Armed Forces took place in the so-called Hall of Victory of the Second World War. It’s is the main hall of the building, right in the middle. Everything in this hall glorifies victory, it is more a monument than a museum, without any room for the reflection. There I did an installation with material from the museum’s photo archives. But my idea was to do an installation not with the photos, but with their archival inventory cards. What I found so interesting about these cards was the fact that they contained no reproductions of the images they inventorized. There was only the textual explanation of what was shown on the (absent) images. The text appeals to your collective visual memory because you have to imagine the images of war that we all have in our heads. Think of the famous (restaged) 1945 photograph of the Red Flag on the Reichstag. So I didn’t show that image (which was in the archives), but instead I showed its card with the photo’s verbal description. I took thirty six such cards that told the story of the Second World War, from the beginning to its last days.

SS: Do you see yourself in a line of work often identified as “Institutional Critique”?

MT: Of course in some cases my work functions as an Institutional Critique. But in this case we’re talking about a museum run by the Russian Ministry of Defense; this is a very special kind of museum. It has not only nothing to do with art, but it has nothing to do with any kind of cultural discourse in general, even with history. That’s because this is a museum that is a direct representation of the Red Army, of how the Red Army wants to be seen. The whole history of the Red Army is represented in this museum by the Army itself, not by historians. For me, that was the challenge. Another aspect is that I want to draw attention to the huge potential of Soviet knowledge and Soviet archives. The problem is that this potential, and the history it reflects, must be reflected upon, if not revised. This is something that was never done after the fall of the Soviet Union.

SS: And you believe that such reflection inside these institutions such as museums and archives can be begun by artists?

MT: Yes, yes I think so. In Germany, the same is happening with some ethnographic museums. Of course they’re much more progressive than such museums in Russia, but even so they feel they lack the tools for representing all the material they have, and they are asking artiststo work with their collections. In Russia, such museums would never ask artists to work with their collections. Not because they are scared, but because they would never come up with the idea of working with the artist.

SS: For artists in countries like Russia, one way out of the dilemma of being excluded from museums and archives has always been the creation of their own archives and museums. We know that in Moscow Conceptualism this was a real strategy. What’s interesting about your work is that you work with existing institutions, persuading their directors to let you in to work with their material. This is a very different approach. The Moscow conceptualists picked up the fragments of Soviet life and transferred them to a context that was utterly of their own, the artists’, making. Whereas the context you choose is the context of real institutions.

MT: That’s really one of the key points for me: I was never interested in making archives. I am more interested in rethinking existing museums and archives. As you say, the Moscow conceptualists were focused on creating archives from nothing, from the poor objects of Soviet everyday life.

SS: Kabakov for instance creates fictitious institutions. He has no interest in actual Soviet museums or collections.

MT: As I see it, the importance of Kabakov’s model is to draw attention to the misery of everyday Soviet life, and to make it important in this way. Because something that is not important can’t be institutionalized. And this institutionalization of “nothing” is the key moment for Kabakov. In my case, it’s more like the reverse. We have these institutions, which, never have never been reformed after the fall of USSR, and that still have a big influence over collective consciousness in Russia on a lot of levels: economic, political, and sociological. It’s very important, I think, not to destroy these institutions, but to rethink their position and our point of view on it. My focal point is not a critique of the institution but rather their perspective on their own material and its display. That’s why at the Armed Forces Museum I designed glass vitrines for my installations that looked exactly the same as theirs. I was trying to produce the same visual language, but in a way that would allow me to criticize the institution’s perception of the material rather than the institution itself. This is the main difference for me.

SS: Many thanks!

Berlin, February 2017

(Transcription Gabriel Wilson, Chicago)

Mikhail Tolmachev studied at the Izvestia School of Documentary Photography and graduated from the Institute of Contemporary Art in Moscow. Tolmachev left Russia to study at the Academy of Visual Arts in Leipzig where he graduated with honours in Media Arts. Tolmachev’s work SLON, an investigation into propagandistic imagery and flaky oral history, was recently shown at Palazzo Zattere, Venice.

Mikhail Tolmachev studied at the Izvestia School of Documentary Photography and graduated from the Institute of Contemporary Art in Moscow. Tolmachev left Russia to study at the Academy of Visual Arts in Leipzig where he graduated with honours in Media Arts. Tolmachev’s work SLON, an investigation into propagandistic imagery and flaky oral history, was recently shown at Palazzo Zattere, Venice. Sven Spieker lives in Los Angeles and Berlin and teaches at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Book publications include Bürokratische Leidenschaften. Kultur- und Mediengeschichte im Archiv (ed., 2004); The Big Archive. Art from Bureaucracy (2008); Destruction (ed., forthcoming). Spieker is a founding editor of ARTMargins.

Sven Spieker lives in Los Angeles and Berlin and teaches at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Book publications include Bürokratische Leidenschaften. Kultur- und Mediengeschichte im Archiv (ed., 2004); The Big Archive. Art from Bureaucracy (2008); Destruction (ed., forthcoming). Spieker is a founding editor of ARTMargins.