Special Issue: Artistic Reenactments in East European Performance Art, 1960–present

The reenactment of artistic performances and actions has garnered much curatorial attention in recent years. Life, Once More: Forms of Reenactment in Contemporary Art, at Rotterdam’s Witte de With in 2005 was an exhibition that explored the reenactment of historical events, while Marina Abramović’s series of performances, Seven Easy Pieces, which took place that same year at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, involved Abramović reenacting artistic performances both by herself and other well-known and established performance artists, such as Joseph Beuys, VALIE EXPORT, Gina Pane, and Vito Acconci. Other, perhaps less well-known explorations of performance reenactment include: Czech artist Barbora Klímová’s project Replaced-Brno (2006) in which she reenacted the performances of five (male) Czechoslovak artists working during the communist period; and the bureau of contemporary art praxis group Kontejner’s The Orange Dog and Other Tales (Even Better than the Real Thing (2009), billed as an “art history play,” in which body and performance art works from the (then) unwritten history of Croatian performance art were reperformed. (One could also mention and RE: akt! Reconstruction, Re-enactment, Re-reporting (2009), an exhibition in 2009 in Rijeka, Croatia; Ljubljana, Slovenia; and Bucharest, Romania, which explored the re-enactments of the Slovenian group OHO’s 1969 action Mount Triglav by Janez Janša, Janez Janša and Janez Janša (Mount Triglav on Mount Triglav, 6 August 2007) and Eva and Franco Mattes’s re-enactment of Marina Abramović and Ulay’s Imponderabilia. Theatre director Janez Janša has also created a series of re-enactments of Imponderabilia in a work entitled Life II [In Progress], in which the original figures of Abramović and Ulay are replaced by a series of individuals who change over time: male and female couples transform and expand, growing families as the females’ pregnancies are revealed in subsequent photographs. In later photographs, the adults appear with the children that they have spawned.)

These explorations of reenactments conform largely to Cold War-era geopolitical boundaries, with Seven Easy Pieces focusing on the now canonical works of performance art in Western Europe and North America—the one exception being Abramović’s reenactment of her own work, Lips of Thomas, as part of Seven Easy Pieces in 2005, originally performed in 1973 at the Galerie Krinzinger, Innsbruck.(However, given that Abramović left Yugoslavia in the 1970s, her relationship with Eastern Europe, and her identification as an Eastern European artist, is complicated. Additionally, this piece was originally performed in Austria, not in Eastern Europe.) Likewise, Replaced-Brno and The Orange Dog… were constructed along national lines by artists and curators in Central and Eastern Europe, in relation to their own countries’ respective performance art history. Consequently, the theory of reenactments, much like that of performance art, remains restricted to a consideration of only Western European and North American performances.

These explorations of reenactments conform largely to Cold War-era geopolitical boundaries, with Seven Easy Pieces focusing on the now canonical works of performance art in Western Europe and North America—the one exception being Abramović’s reenactment of her own work, Lips of Thomas, as part of Seven Easy Pieces in 2005, originally performed in 1973 at the Galerie Krinzinger, Innsbruck.(However, given that Abramović left Yugoslavia in the 1970s, her relationship with Eastern Europe, and her identification as an Eastern European artist, is complicated. Additionally, this piece was originally performed in Austria, not in Eastern Europe.) Likewise, Replaced-Brno and The Orange Dog… were constructed along national lines by artists and curators in Central and Eastern Europe, in relation to their own countries’ respective performance art history. Consequently, the theory of reenactments, much like that of performance art, remains restricted to a consideration of only Western European and North American performances.

An example of this can be found in Amelia Jones’s and Adrian Heathfield’s substantial publication Perform. Repeat. Record: Live Art in History (2012)—a collection of essays that together attempt to assess the myriad functions and meanings of artistic reenactments—which gives scant attention to the reenactments of performances in or from Central and Eastern Europe. Only one essay, “Reconstruction 2,” by Slovenian artist and theater director Janez Janša, provides a close reading of the mechanics and significance of the restaging of an action from the history of East European performance art or theater, in this case, Pupilija pap Pupilo and the Pupilceks, originally performed in Slovenia (Yugoslavia) in 1969. The book also includes a summary of performance art in Eastern Europe by Angela Hartyunyan and others, entitled “The Interstices of History,” which includes some discussion of reenactments. Serbian artist Tanja Ostoji?’s essay “Assuming a Migrant Woman’s Identity” provides an artist’s statement on her recent work, although this does not necessarily involve reenactment, but rather, a series of performances that develop out of the artist’s experiences with migration. The book also includes a discussion between Abramović and Jones, which is instructive with regard to the Eastern European context of performance art. However this text falls short of giving the phenomenon of reenactments in Eastern Europe its due.

It is my contention that because of the particular manner in which performance art, as a genre, developed in the region—in contrast to the way it developed in Western Europe and North America—reenactments of performances from and in the region warrant targeted attention. The three articles in this special edition of ArtMargins Online—“Performing Oneself into History: Two Versions of Trio for Piano (Tallinn, 1969/1990),” by Anu Allas; “Performativity of the Private: The ambiguity of reenactment in Karol Radziszewski’s Kisieland” by Aleksandra Gajowy; and “Reenactment, Repetition, Return. Ion Grigorescu’s Two Dialogues with Ceausescu,” by Ileana Parvu—together attempt to shed light on the particular resonance of the phenomenon of reenactments specifically in the context of the former communist countries of Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe, through close readings of reperformances in Estonia, Romania, and Poland.(These texts were originally presented as papers as part of a panel that I organized at the Association of Art Historians annual conference in Edinburgh, in April 2016, entitled “Artistic Re-enactments as Vehicles of Cultural Transfer in Eastern Europe.”) As each of these case-studies shows, whether it is the artist reenacting his or her own work, as for example Romanian artist Ion Grigorescu, or an artist reenacting the work of others, as Polish artist Karol Radziszewski did with the work of Ryszard Kisiel, all of these reperformances retrieve and bring a piece of the past into the present. In repeating these previously clandestine acts and by bringing them into the public, these reenactments contribute to the development of a canon of performance art in the region, creating iconic images of these previously unknown works of art.

For the purposes of this article, reenactment denotes the redoing, restaging or re-performing of an artistic performance—meaning a live act or action by a visual artist—and is as such distinct from the repetition of a theatrical performance, choreographed dance, or scored musical performance. The reason for this distinction is two-fold: firstly, theatrical, dance, and musical performances are usually created with the intention of repetition, yet this is not necessarily so with performance art pieces or actions. Secondly, when performance art, as a distinct genre in and of itself, emerged in North America in the 1970s, it did so primarily within the context of the visual arts, with the aim of creating an ephemeral work of art, one that could not be objectified or repeated and, thus, commodified. The failure of such a project became immediately apparent,(See for example, Lucy Lippard’s 1973 ‘Postface’ to Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972 (reprinted in 1997, Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press), p. 263.) as performance artworks quickly took on commercial value, through the sales of limited edition photographs and videos as works of art in and of themselves. As was the fate of most avant-garde movements, performance art in Western Europe and North America was coopted by the mainstream, becoming institutionalized, eventually being taught in art history surveys and studio art classes as another moment in the development of art history.

In Central and Eastern Europe, however, performance art did not emerge from the need to create a noncommercial work of art. In these socialist countries, there was no art market to speak of; for the most part the state was the sole patron of art, and no commercial gallery system existed. The government maintained control over artistic production, and only painting and sculpture were considered legitimate forms of visual art tolerated by the authorities. While the level of control varied from country to country and region to region across Eastern Europe, art forms such as conceptual art, performance art, even installation existed as an alternative, as opposed to official, artistic practice. Most artists pursued these approaches privately, within a close circle of friends. For example, in Russia, the Collective Actions group organized actions and happenings in the remote countryside, inviting only close and trusted friends. They did this not, as Allan Kaprow may have, to escapethe commodified spaceof the gallery, butto escape the policed and politicized space of the city. As Czech artist Karel Miler mentioned in an interview, with regard to the differences between contemporary art in North America and Eastern Europe in the post-WWII period: “we could only dream of consumer society.”(Barbora Klímová, interview with Karel Miler, in Barbora Klímová, Replaced—Brno (exhibition catalogue, no publication information, 2006), p. 54.) Consequently, instead of a reaction against the institutionalization of art, performance art in Eastern Europe often functioned as a zone of freedom in which artists could experiment. (This is, of course, not the only explanation behind the development of performance art in the region. The situation varied from country to country, city to city, across the Eastern Bloc, however, this is one of the main points of continuity with regard to the genre in the region.)

Given its unofficial status in communist Eastern Europe, performance was only rarely presented in the context of institutions, but was more often to be found in the artist’s studio, enacted among trusted colleagues, or in the countryside, documented in order to provide evidence that it occurred. Thus while Kaprow’s Eighteen Happenings in Six Parts was staged at the Reuben Gallery in New York’s East Village in 1959, and Vito Acconci performed Seedbed in the Sonnabend Gallery in 1972, this type of public presentation of performance art, in the context of an art gallery, was nearly impossible in Eastern Europe. (Notable exceptions to this were the performances by Abramović and her colleagues in the Student Cultural Centre in Belgrade in the 1970s. However, the experimental nature of this work was tolerated only because the artists in question were still students, and was thus of little consequence to the authorities. It was often the case that student work was afforded greater tolerance in Eastern Europe, at least tacitly, by the authorities. Insofar as the state did not yet recognize these individuals as professional artists, a status which one usually needed to have an official (and public) exhibition, they didn’t usually pay much attention to student work, so long as it was not political, overtly or otherwise. Poland was another exception to the rule, and performances did take place in gallery spaces, most notably the Galeria Labyrint in Lublin and the Foksal Gallery in Warsaw. But Poland and Yugoslavia were really exemplary in terms of tolerance toward artistic experiment. Furthermore, these levels of tolerance varied not only from place to place, but year to year and decade to decade, as the political situation was constantly changing. Consequently, under martial law in Poland in the early 1980s performances moved out of the galleries and into the streets. Furthermore, in places such as Albania or Moldova, for example, this type of display would have been completely impossible under communist or Soviet rule.) In Czechoslovakia, Karel Miler, Jan Ml?och and Petr Štembera created some of the most visceral pieces of body art in the country in the 1970s, and while many of these were staged in the basement of an official institution, the Museum of Applied Arts in Prague, where Štembera worked, the artists held these events outside of regular opening hours, without the knowledge of the authorities.

Scholars writing about reenactments of performance art in Western Europe and North America largely agree that this phenomenon originates with the desire to get to know the past, and to provide some semblance of permanence to the fleeting live act. In Jones’s words, key to reenactments is “an interest in how time, memory and history work—and how or whether we can retrieve past events.”(Amelia Jones, “ ‘The Artist is Present’: Artistic Re-enactments and the Impossibility of Presence,” The Drama Review, vol. 55, no. 1, Spring 2011 (T209),p. 25.) Similarly, Branislav Jakovljevi? maintains that reenactments give past performances “a second chance, reperformance supplies precisely that which its precursors renounced: permanence.”(Branislav Jakovljevi?, “On Performance Forensics: The Political Economy of Reenactments,” Art Journal, vol. 70, no. 3 (Fall 2011), p. 51.) For Sven Lütticken, “reenactments are an attempt to create an experience of the past in the present, or as much present as possible.”(Sven Lütticken, “An Arena in Which to Re-enact,” in Rod Dickinson, ed., Life, Once More: Forms of Reenactment in Contemporary Art (Rotterdam: Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, 2005), p. 27.) We see this clearly in the reenactments of performances in Estonia, Romania, and Poland discussed in this special edition, as the artists in question attempt to bring events of a past and quite different socio-political time and context into the present.

In some instances, this transplanting of the past into the present has been used to help create a canon of performance art in the country in question. For example, in Croatia, the collection and staging of performance reenactments in The Orange Dog and Other Tales was done as an attempt to perform the history of performance art in Croatia. The curators state that the project “uses a series of reenactments to create an (art) history theater play, whose plot evolves into a history of Croatian performance art. It is a work of art historians turned into a drama, instead of a scientific paper.”(See the project description at http://stari.kontejner.org/the-orange-dog-and-other-tales-even-better-than-the-real-thing-english (last accessed May 16, 2017).) This, in turn, enables the canonization of these performances, whose history was only codified in print in 2014, with the publication of Suzana Marjani?’s The Chronotope of Croatian Performance Art: from Traveleri until Today. In this instance, performance, and its reenactment, function as research, with the artist performing the function of the art historian, critic or institution. Rather than writing that history, the curators turned it into an action to be witnessed, experienced and embodied.()

In reperforming a work of experimental live art from the socialist period in Eastern Europe in the present day, there is a significant shift in socio-political context from the original instantiation. In many cases, performance art in the socialist period was only tolerated because it simply was not recognized as art. With painting and sculpture as the only officially sanctioned art forms, performance, if it was not too extreme, unusual or political, could escape under the radar. Such was the case with Czech artist Ji?í Kovanda, who, in the 1970s, created a number of performances on the streets of Prague that were only permissible in the public space because they were entirely invisible. Theatre, for example, which he performed in Wenceslas Square in the center of the city in 1976, involved the artist enacting a series of everyday gestures, such as scratching his nose and brushing his hand through his hair, all imperceptible as a performance, and only enacted long enough for the photographer to document the action. In 2006, the young Brno-based Czech artist Barbora Klímová (b. 1977) reenacted several of Kovanda’s works in the dramatically different context of the post-communist Czech Republic. In addition to the temporalchange, the artist also changed the location of several of the performances, enacting them in different spots than the original. Unlike in the 1970s, it is possible that those passing by Klímová would be more aware of (and perhaps more receptive to) contemporary art and performance art. More importantly, her reenactments transplanted the artworks from a context in which these acts were only able to function as art if the artistic aspect of the work was clandestine to one in which they could be openly acknowledged as art, and performed as works of performance art. In this regard, the reperformance in the post-socialist period of experimental artworks from the 1960s and 1970s in Eastern Europe, has the potential to transform the meaning, reception, and significance of these acts by presenting them in a context entirely different from whence they emerged.

This was precisely Klímová’s motivation for reenacting these performances. In addition to Kovanda’s work, she reenacted performances by four other artists from the Czech scene active in the 1970s and ‘80s in order to better understand the socio-political and cultural space in which these historical performances were created in Czechoslovakia, and how that space had changed over time. One of the artists whose work she reenacted, Milan Kozelka, challenged her: “Why do you want to do these reconstructions? Those performances will lose their meaning at this time.”(Milan Kozelka, in an interview with Barbora Klímová, in Replaced—Brno, 38.) But for Klímová, this change in meaning is precisely the point. Consequently, the reenactment of performances from the socialist era in post-socialist Central and Eastern Europe can provide a unique insight into the very dramatic socio-cultural shifts that took place during the gap in time between the original act and its reiteration.

Because of the dramatic socio-political changes that took place in Central and Eastern Europe at the end of the 1980s, the shift in context between the original performance and its reenactment is inevitable. This is not necessarily always the case with regard to reenactments of performances from Western Europe and North America. For example, one key difference between Abramović’s reenactment of Acconci’s Seedbed (or of her own Lips of Thomas performance, for that matter) and the reenactments by Girgorescu, Radziszewski, and others discussed in this special edition, is the change, or lack thereof, in context. Although Abramović transported the location of Acconci’s performance from a lower East Side gallery to the Guggenheim, regardless of the magnitude of the latter as an institution, both performances still took place within the context of an art institution (as did her Lips of Thomas). Grigorescu’s 2007 performance and DVD, Postmortem Dialogue with Ceaucescu, a reenactment of his 1978 performance and film Dialogue with Ceaucescu, however, shifted the site of action from the privacy and seclusion of the artist’s studio within the repressive space of Ceaucescu’s Romania, to a public space in the postcommunist, newly democratic country. This shift was accompanied by a dramatic change in audience; whereas the artist created the earlier piece with no intention of making the film public, in post-communist Romania he made the piece precisely to be displayed in a museum or gallery context. With the reenactment, the piece shifted from something not fit for public consumption to something intended precisely for it.

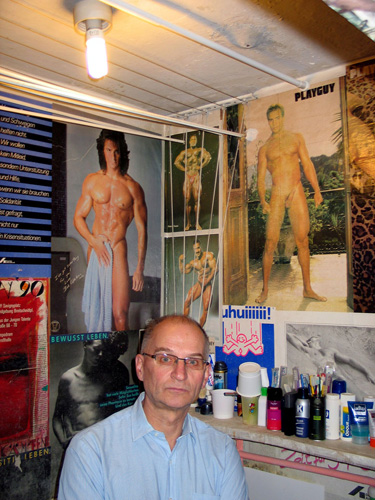

This determination to avoid discovery can be witnessed that much more dramatically in the examples chosen for reenactment by the young Warsaw-based Polish visual artist, photographer and publisher Karol Radziszewski (b. 1980). In 2012, he restaged a series of homoerotic photographs created by the amateur photographer Ryszard Kisiel, founder and publisher of the first communist-era gay zine Filo, in 1985 and 1986. Kysiel created these images during the period of Operation Hyacinth, which consisted of raids and interrogations of those suspected and accused of homosexual activity. While Kisiel’s photographs, which were originally constructed under fear of persecution and incarceration in the People’s Republic of Poland, were never intended to be shown beyond the close sphere of trusted friends, the reenactments of these scenes in the context of a newly democratic Poland were done with the express purpose of bringing them to a wider public by a rising young artist. (Although homophobia is still an issue in contemporary Poland, homosexuality is no longer a criminal offense.)

This determination to avoid discovery can be witnessed that much more dramatically in the examples chosen for reenactment by the young Warsaw-based Polish visual artist, photographer and publisher Karol Radziszewski (b. 1980). In 2012, he restaged a series of homoerotic photographs created by the amateur photographer Ryszard Kisiel, founder and publisher of the first communist-era gay zine Filo, in 1985 and 1986. Kysiel created these images during the period of Operation Hyacinth, which consisted of raids and interrogations of those suspected and accused of homosexual activity. While Kisiel’s photographs, which were originally constructed under fear of persecution and incarceration in the People’s Republic of Poland, were never intended to be shown beyond the close sphere of trusted friends, the reenactments of these scenes in the context of a newly democratic Poland were done with the express purpose of bringing them to a wider public by a rising young artist. (Although homophobia is still an issue in contemporary Poland, homosexuality is no longer a criminal offense.)

The shift in the site of performances in Eastern Europe, from unofficial private spaces to the institutional spaces of the museum or gallery exhibition, was accompanied by the shift from the noncommercial to the commercial. Both Jones and Jakoljevi? agree that the market has played a role in the development of reenactments. And capitalism, which, as Jakoljevi? contends, seeks to “extend (and profit from) the promise of future repetitions,”(Jakovljevi?, p. 50.) seems to provide the perfect conditions for cultivating reenactments, in either Eastern or Western Europe. Jones, however, maintains that both reenactments and the study thereof can be instructive with regard to the commercialization of art. Her article, “The Impossibility of Presence,” demonstrates how “the performative re-enactment, when critically engaged, can remind us… how closely all cultural expressions are tied to the marketplace in late capitalism…”(Jones, p. 42.) If that is the case, then it seems that even more insight can be gleaned from the study of performances from socialist-era Central and Eastern Europe—where market forces were virtually nonexistent—which were then re-performed in the newly developing free markets of the region.

For example, whereas Kovanda commented that performance art in the 1970s was a phenomenon “more personal than social,”(Ji?í Kovanda, in an interview with Barbora Klímová, in Ibid. p. 31.) his colleague Jan Ml?och, discussing the reenactments of their performances in the 1990s, lamented the fact that “what had been personal in the 1960s turned into a feast for live TV”(Jan Ml?och, in an interview with Barbora Klímová, in Ibid. p. 27.) in the post-communist space. Similarly, as Anu Allas discusses in her article, when Estonian artists Ando Keskküla, Ülevi Eljand and Leonhard Lapin reperformed their 1969 happening, Trio for Piano,(In the original 1969 happening, these three artists were joined by Andres Tolts, however he did not participate in the re-enactment.) in 1990, they did so in the context of a new world order, in order to assert their presence as established members of the art community, and canonize their work during that particularly potent period in political history. The artists, who were students in the 1970s and forced to confine their experimental work to their own private activity, suddenly faced a younger generationof artists in post-Soviet Estonia engaging openly and freely with performance, without much knowledge of their pioneering activity. The reenactment of this early and important, but lesser-known and certainly not canonized happening, was an attempt to cement their position as avant-garde artists of contemporary Estonian art.

For example, whereas Kovanda commented that performance art in the 1970s was a phenomenon “more personal than social,”(Ji?í Kovanda, in an interview with Barbora Klímová, in Ibid. p. 31.) his colleague Jan Ml?och, discussing the reenactments of their performances in the 1990s, lamented the fact that “what had been personal in the 1960s turned into a feast for live TV”(Jan Ml?och, in an interview with Barbora Klímová, in Ibid. p. 27.) in the post-communist space. Similarly, as Anu Allas discusses in her article, when Estonian artists Ando Keskküla, Ülevi Eljand and Leonhard Lapin reperformed their 1969 happening, Trio for Piano,(In the original 1969 happening, these three artists were joined by Andres Tolts, however he did not participate in the re-enactment.) in 1990, they did so in the context of a new world order, in order to assert their presence as established members of the art community, and canonize their work during that particularly potent period in political history. The artists, who were students in the 1970s and forced to confine their experimental work to their own private activity, suddenly faced a younger generationof artists in post-Soviet Estonia engaging openly and freely with performance, without much knowledge of their pioneering activity. The reenactment of this early and important, but lesser-known and certainly not canonized happening, was an attempt to cement their position as avant-garde artists of contemporary Estonian art.

The question of iconicity is important when it comes to reenactments. Sven Lütticken has gone so far as to claim that the photographs and videos of original performances are “in many cases so well-known that a reenactment will risk seeming like a sham, a poor substitute for the auratic images of the original event.”(Lütticken, p. 24.) Furthermore, Jones has commented that it would be difficult to pinpoint the origin of an “iconic” work of performance art, insofar as “almost all performance artworks were performed more than once in their earlier incarnation.”(Jones, p. 24.) While there may be a number of performance art works from Western Europe and North America cemented in one’s mind through repeated exposure to iconic photographic images, one can point to few “iconic” works of performance art in Central and Eastern Europe that were indeed “iconic” prior to their mass circulation following the dissolution of the Eastern Bloc. Secondly, and to counter Jones’s claim, few of these action-based artworks were performed more than once as they may have been in the West. Since the images of performance art in Eastern Europe did not circulate in the same manner that they did in Western Europe and North America, this risk of presenting a “sham” is not present when reenacting performances in the region, which gives their restaging an entirely different resonance.

Aside from an absence of an art market, another reason that the documentation of performances in Central and Eastern Europe did not become iconic relates to the manner in which that documentation was preserved. For the most part, photographs (and rare videos) of performances in Eastern Europe during the socialist period were kept in personal archives, and not purchased by museums, galleries or collectors. Many artists in the region describe the function of documenting their performances as akin to placing them in a time capsule, for some future, unknown audience to view,(For example, Iosif Király, in an interview with the author in Bucharest, March 26, 2014, explained that he photographed his performances for a “future audience.”) which Croatian art historians and curators Ivana Bago and Antonia Majaca have referred to as a “delayed audience.”(See Ivana Bago and Antonia Majaca, “Dissociative Association, Dionysian Socialism, Non-Action and Delayed Audience: Between Action and Exodus in the Art of the 1960s and 1970s in Yugoslavia,” in Ivana Bago and Antonia Majaca (eds), in collaboration with V. Vukovi?, Removed from the Crowd: Unexpected Encounters I (Zagreb, Croatia: BLOK, 2011), pp. 280–82.) While in the West, documents of this “ephemeral” art form were quickly transformed into saleable objects and exhibitable commodities, this transformation came much later for artists in Eastern Europe, and in most cases not until the 1990s.

Jones sees the iconicity of performance art works as central to the issue of reenactments, contending that several questions are raised in the context of the current “rage” for reenactments:

“What performances get talked and written about in the culture(It is interesting that Jones does not specify to which “culture” she refers here, although it seems to be implicit that she is talking about the inclusions and exclusions within Euro-American culture, rather than the exclusion of Central and Eastern Europe (or other areas) from the canon as a whole.) as a whole? Which get written into history and in what ways? How and why do historianswrite certain things into the present, excludeothers, and continually fix and re-fix the meaning of objects as well as events in order to bring them into a continually refreshed “present”? And how does that hallowed “present”…inevitably include and even depend on the circuits of the marketplace, which itself makes and informs “histories” as we know them?”(Jones, p. 42.)

Insofar as these are the questions that perennially haunt the scholar of Central and Eastern European art history, it follows that the study of reenactments of performances in and from the region can be equally instructive for the Western context as it can for the former socialist region of Europe.

It is not simply that contemporary art and performance art from Central and Eastern Europe is, for the most part, excluded from the wider art historical canon. Performance art, along with other experimental practices, have yet, in most instances, to make it even into the canon of local art histories in the region. There are a number of reasons for this. Insofar as the state had control over artistic production, it also held sway over art criticism, which did not evolve as a practice in the region to the extent that it did in the West. While there were artists and critics who were involved with and supportive of the experimental art scene, whatever texts they did produce did not circulate as widely as similar texts in Western Europe and North America, and often they circulated as samizdat. In many cases, art history and criticism evolved as an oral tradition, as artists and art historians used the public forum of the art exhibition or meetings in artists’ studios to discuss, rather than publish, art criticism.

In most cases, the academy in Eastern Europe under socialism did not have the same function as it did in the Western Europe and North America—for example, as a vehicle for the transfer of artistic ideas, approaches, genres and styles from one generation to the next. For example, one can point to Allan Kaprow’s studies with John Cage at the New School in New York as seminal to his development of Happenings and performance. But when asked about her artistic predecessors in Croatia, Sandra Sterle mentioned that she learned about artists, such as Sanja Ivekovi?, after completing art school, because the artists from the generation active in the 1970s didn’t become teachers. “We lost something [as a result],”(Sandra Sterle, in a Skype interview with the author, April 24, 2014.) she commented. While in the West, the academy may not have immediately integrated performance art, it eventually did. However, in Eastern Europe, in many instances performance art is still not taught as a genre in its own right (either in art history or studio classes), and in other instances it is only starting to be so.(The manner in which performance art developed in the region is complicated and complex, and varies from country to country. I attempt to outline these various trajectories in my book Performance Art in Eastern Europe since 1960 (Manchester University Press, 2017). For the most part, my experience in the region was that young artists rarely learned about performance art during their formal studies. In Romania, where performance art emerged from contemporary dance, as opposed to the visual arts, several young artists I interviewed told me that they did learned about performance art through the Internet, rather than in art school. Similarly, Serbian artist Branko Miliskovi? recalled first coming across the genre of performance art when he saw a poster with an image of Marina Abramović on the façade of the Student Culture Centre in Belgrade, where she had performed in the 1970s. Performance was something that artists in the 1960s and 1970s read about through several well-circulated texts (usually as samizdat, or from “special shelves” in the library), such as Allan Kaprow’s Assemblages, Environments & Happenings (1966), Michael Kirby’s Happenings (1965), and eventually Roselee Goldberg’s Performance: Live Art, 1909 to the Present (1979). These texts, their ideas, and the performances contained within, however were not taught in art schools at all.) Thus the case studies in this special issue should serve as the necessary first step in expanding the discourse on artistic reenactments of performance art from the former socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe.

This article is part of the Special Issue on Reenactment in Eastern Europe. Other articles in the issue include:

Dr. Amy Bryzgel is Senior Lecturer in Film and Visual Culture at the University of Aberdeen, where her research focuses on performance art from Eastern Europe. She has just published a monograph with Manchester University Press (2017) entitled Performance Art in Eastern Europe since 1960. In addition to her research and teaching on contemporary art, she is Director of the George Washington Wilson Centre for Visual Culture and Director of Postgraduate Studies in the School of Language, Literature, Music and Visual Culture at the University of Aberdeen. She is also a Director of the Demarco Archive Trust.

Dr. Amy Bryzgel is Senior Lecturer in Film and Visual Culture at the University of Aberdeen, where her research focuses on performance art from Eastern Europe. She has just published a monograph with Manchester University Press (2017) entitled Performance Art in Eastern Europe since 1960. In addition to her research and teaching on contemporary art, she is Director of the George Washington Wilson Centre for Visual Culture and Director of Postgraduate Studies in the School of Language, Literature, Music and Visual Culture at the University of Aberdeen. She is also a Director of the Demarco Archive Trust.