Where Gravity Doesn’t Apply: An interview with Igor Ivanov about his film Upside Down (Macedonia, 2007)

Hideous corners of the city, scenes without a trace of sophistication, depressing enclosed spaces – this is the setting chosen for the desperate life drama of young Jan Ludvik. Its individual chapters are recalled as retrospectives by Jan himself as he travels in a train hurtling through the darkening landscape, in the company of a random female passenger whose miserable exterior renders her the embodiment of the bleakest of destinies. Jan was a gifted student and, by some strange quirk of fate, also a talented circus artist, but the world in which he lives drives him only to self-destructive actions. Everything is marked by degradation, even love, for which cheap porn clubs are often an eloquent stage, and whose object is a palpably degenerate girl; several scenes are deliberately set in dingy, graffiti-covered urinals.

From the description of the film at the 42ond Karlovy Vary International Film Festival (http://www.kviff.com/en/film-detail/1995-upside-down/).

The Macedonian feature film Upside Down by Igor Ivanov was part of the “East of the West -Films in Competition,” a section of the International film festival in Karlovy Vary (Czech Republic). Upside Down is a co-production of “Sektor Film” (Macedonia), “Mainframe Productions” (Croatia), and “Cinears” (Serbia). Filming took place in Skopje between November 2005 and May 2006, with the post-production completed in Budapest, Vienna and Zagreb. The script for Upside Down was written by the novelist Venko Andonovski and the director himself. The film premiered in Skopje on 28 September 2007.

The world premiere of Upside Down took place on the 4th of July 2007 in the Karlovy Vary theatre. Natascha Drubek-Meyer attended the screening and asked the director a few questions about his feature film debut.

Warning: This interview contains plot spoilers.

NATASCHA DRUBEK-MEYER: Your film was very well received by the audience at the festival Karlovy Vary in July 2007. Did you get feedback from the viewers concerning your film? When and where will it be screened more widely?

IGOR IVANOV: The feedback from the viewers was great, and I am really satisfied. I am aware that this is not a mainstream film, neither in terms of its subject, nor in terms of following current film trends. I think that festivals are its most correct destination, where the film can have a deeper impact, where there is a ground for that. Karlovy Vary was the right place for the world premiere of this film. The audience and the critics gave it epithets of “dark,” “cruel,” “uncompromising,” “return to expressionism,” “black wave” …All this makes me really happy, because it is giving Upside Down some sort of exclusivity; no one is dealing with the narrative or geographic component as it usually happens, but all of the reviews are about the cinematic aesthetics.

N.D.M.: Please tell me something about the actor who played the main hero. Why is the hero’s name Czech (Jan Ludvík)?

I.I.: The name of the actor is Milan Tocinovski, and he is a film editor. We made a really wide effort in casting for this role, but I did not succeed in finding the character among Macedonian actors. I was looking for a specific physiognomy and a person with similar background as the character. I did the same with Lucija. Neither Milan nor Sanja is a professional actor. This has some evident disadvantages, but on the other hand, they are perfect plausible, on the level of documentary.

The name Jan is Czech and comes from the novel by Venko Andonovski, which was the inspiration for making this film. Venko himself took it from Kundera’s novel The Joke; in a post-modern manner he named its main heroes after the main heroes of Kundera.

N.D.M.: What attracted you to the rather complex novel Navel of the World (Papokot na svetot, 2000) by Venko Andonovski?

I.I.: The atmosphere. Nothing but the atmosphere, some kind of reminiscence, a memory, déjà vu of something we have experienced, and yet we do not know when and where.

N.D.M.: How is the title of the film (Upside Down, in Macedonian: Prevrteno) connected to the title of Andonovski’s novel (Navel of the World)?

I.I.: Upside Down is the title that, according to me, suits the film best and has nothing in common with Navel of the World. Upside Down is not a screen version of the novel, but a distinctive isotope, based on the same axis upon which the novel was written; it goes in a completely different direction, trying to reach pure movie expression: something which cannot be written down and experienced through words.

N.D.M.: The film – at least in the English version – has a very strong aphoristic tendency, such as the following: “Death is a beautiful woman who takes everything one has”; or, in the scene in which the two men peep through a hole and watch the girl washing and say, “She is in the light, we are in the dark.” Do these – sometimes quite monumental – aphorisms originally come from Venko Andonovski’s novel?

I.I.: Some come from Andonovski’s novel, some don’t. These two that you quote are in the scenario, and do not exist in the book. Nevertheless, the style of Venko is exactly the same, beautiful narration and atmosphere, followed by poetic aphorisms, which I really like, because these lines either contain the whole novel or the whole film or the film is coming from them.

N.D.M.: There are several visual upside-downs in this film. I personally enjoyed one of Jan’s perspectives … the one from the coffin. Was it a visual idea that stood at the beginning of the film?

I.I.: Of course.

N.D.M.: Are you a fan of Murnauss’ Nosferatu? The legless party activist reminded me of Max Schreck…

I.I.: The last time I saw Nosferatu was ten years ago. But I saw it for a first time when I was ten or eleven and I remember that I couldn’t sleep for a week or two. I have poster of Nosferatu in my home. I am fond of it.

N.D.M.: The film is a co-production of Macedonian, Croatian and Serbian institutions. What exactly did that mean for the filming itself?

I.I.: Nothing.

N.D.M.: Can you tell us something about Macedonian film?

I.I.: Art films—and, in fact, any film—is difficult to get made in Macedonia, which is a small country. The Macedonian film starts in 1903 with the brothers Manaki and with organized production and feature films in the fifties. Our average is one film per year and I think that fifty movies in our history is above all expectations.

N.D.M.: Would you call this film political in some way?

I.I.: This film is dedicated to the children of the transition, the generation to whom I belong. Educated in the spirit of communism, witnesses and participants in its collapse, pioneers of rudimentary, raw capitalism… children of a transition, which does not end, having started as a period of change, but became a system. No one knows politics better than us, the children of the transition; this is an inevitable component of this film.

N.D.M.: The hero is sometimes seen traveling by train.

I.I.: The “Train of Death”….

N.D.M.: Jan appears to cross a border several times. His passport is checked. Is this a national border? Who is traveling with him? Who is the blonde with torn stockings?

I.I.: Plausibility – this is the most difficult thing when you are dealing with the irrational. But the good thing is that nobody knows how it is there in the Train of Death that carries us from life to death. Religions say there is a border. If there is, I would like it to be like this one, looking normal, with a passport control.

Who is the blonde? Many people ask this, who is she? And I always ask them what do you think? And they say “an Angel,” or “Death,” or the “Angel of Death, but why does she look like a whore?” Because death is a whore, don’t you think? It was my objective to make this character “open,” a “question,” because the death is the biggest question. We don’t know anything about “her.”

N.D.M.: The film is made from an outspokenly male perspective. Jan seems to be the victim of evil females: the blonde female figure of Death on the train, the strange classmate whom he tries to impress with a copied poem by Rimbaud shows her intellectual and social superiority at every single instant. And even his mother, who seems to be the cause of his fall in the circus tent, is a highly ambivalent figure. Can you comment upon that?

I.I.: The film is not made from a male perspective, it is made from Jan’s perspective, and this is a big difference. It is not how it is, but how he sees it all with his eyes.

N.D.M.: Can you name your favorite directors in American and Russian Cinema?

I.I.: This is always the most difficult question, but I will try to give you the ones that come first to my mind, and probably that would be the most honest answer. American: David Cronenberg, Jim Jarmusch, and Francis Ford Coppola.

Russian: 3 x Andrei! Andrei Konchalovsky, Andrei Zvyagintsev, Andrei Tarkovsky.

N.D.M.: What does the circus in film mean to you?

I.I.: The circus is not part of society; it offers an anti-perspective, like that of a monastery. And inside it you are outside of the law, not only in social or political meaning, but in terms of pure physics, as well. In society the crowd is the gravity that forces you down, towards them. In circus, gravity does not apply.

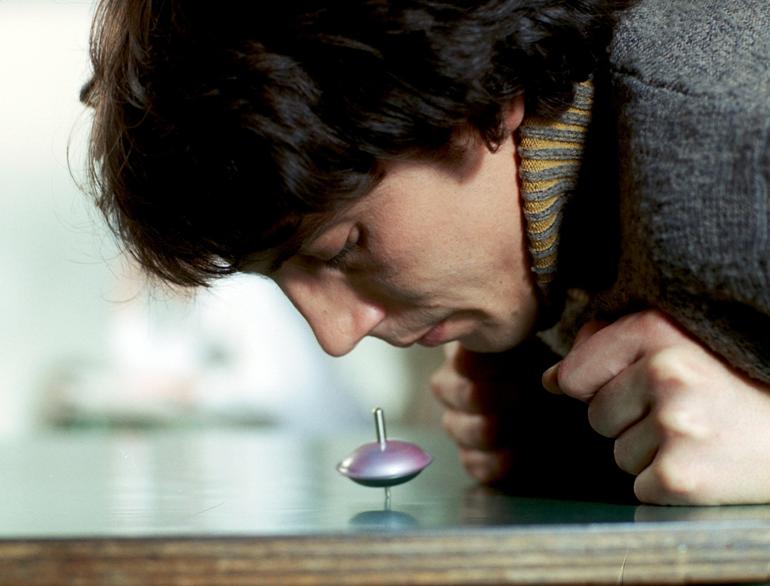

N.D.M.: There are two basic movements in this film connected to Jan: The vertical and the circular movement. Why did you choose a top as a personal emblem for Jan?

I.I.: I can’t really answer this. Symbols are simpler than words, and this is the reason that I like to make films.

Igor Ivanov (born 1973 in Skopje) studied philosophy. His film career started in 1993, when he began directing a series of films for television. Between the years 1995 and 2004 he made several documentaries and short films; one of them, Bugs (Bubacki, 2004, 15 min.), won the Golden Leopard at the Locarno festival. Upside Down is his feature film debut. “The film clearly revives the poetic quality of the so-called “Black Wave” in Yugoslav film during the 1960s, which closely examined the afflictions of society’s “other face” and the fatal dimensions of human existence.” http://www.kviff.com/en/film-detail/1995-upside-down/

Upside Down, color, 35 mm, directed by Igor Ivanov (2007; Macedonia, Croatia, Serbia: 105 min).

Screenplay: Venko Andonovski, Igor Ivanov; Dir. of Photography: Tomi Salkovski; Music: Zoran Spasovski.