“Women’s House”: Sanja Iveković Discusses Recent Projects (Interview)

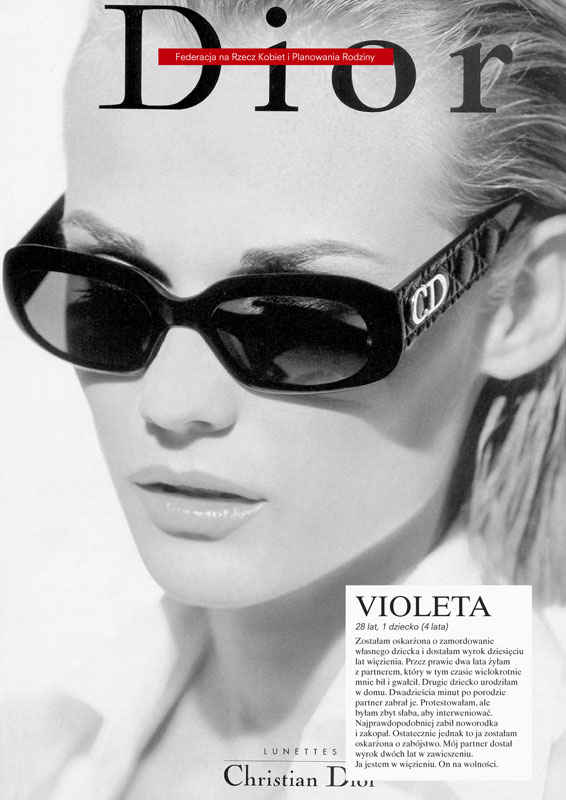

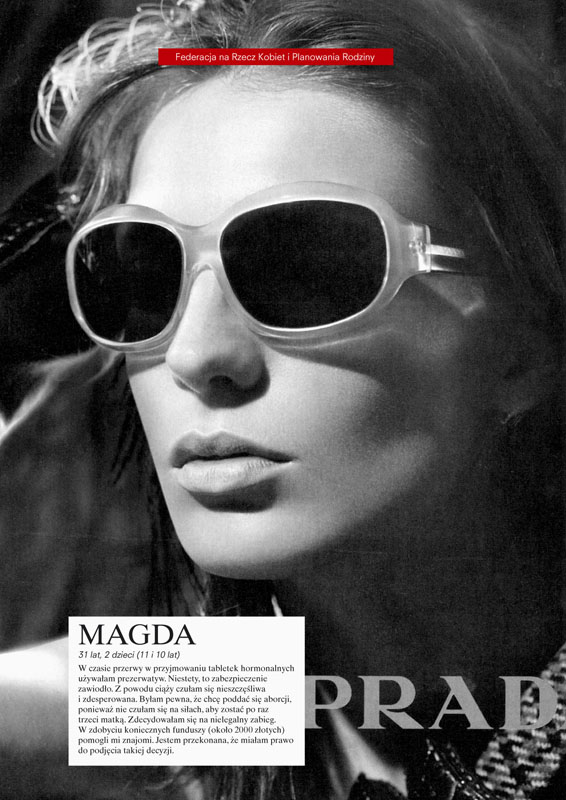

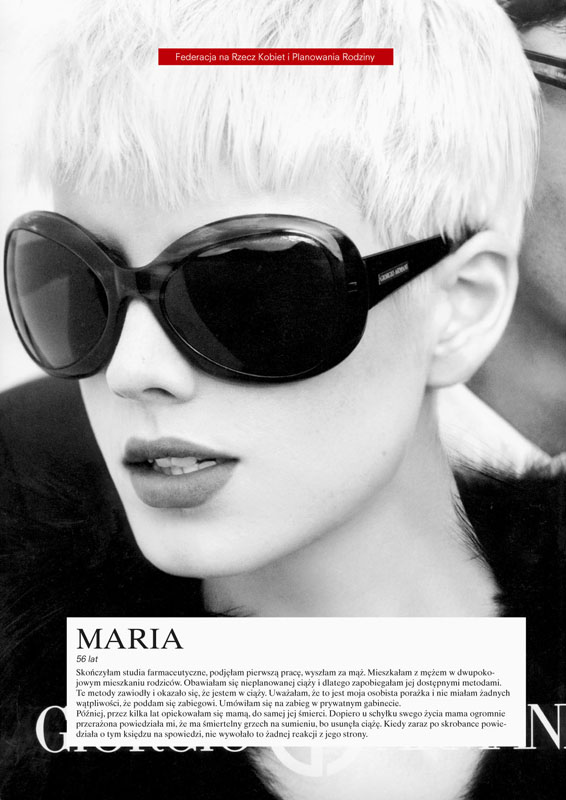

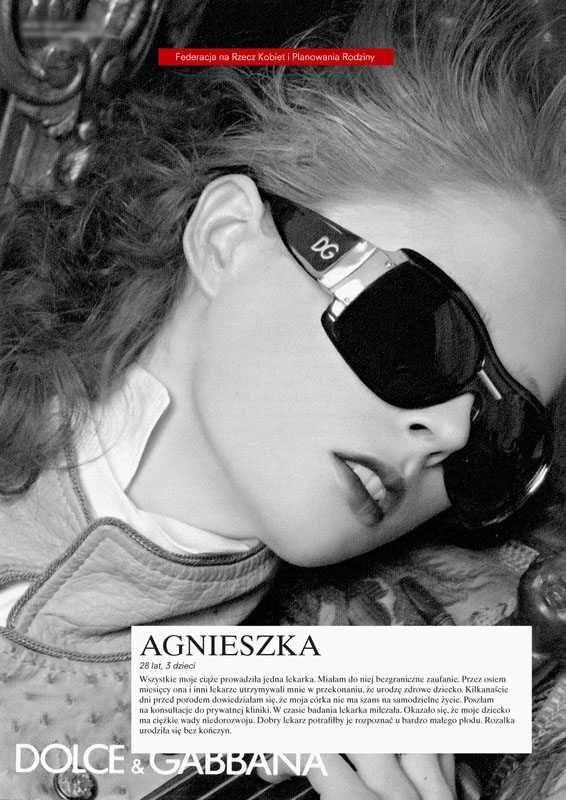

Sanja Iveković was born in Zagreb where she continues to live and work. Since the 1970s Ivekovi? has worked with performance, video, installation, and public action. Her work has been shown at many international exhibitions. The following interview was produced when the artist opened her first solo show in ?ód? (“Practice Makes the Master”: 10/17/2009–12/13/2009). The show was curated by Magdalena Zió?kowska and was accompanied by a public project. The project was a Polish version of Ivekovi?’s ongoing project Women’s House (Sunglasses) in which she appropriates advertising for sunglasses in an effort to tackle the issue of violence against women.

Sanja Iveković was born in Zagreb where she continues to live and work. Since the 1970s Ivekovi? has worked with performance, video, installation, and public action. Her work has been shown at many international exhibitions. The following interview was produced when the artist opened her first solo show in ?ód? (“Practice Makes the Master”: 10/17/2009–12/13/2009). The show was curated by Magdalena Zió?kowska and was accompanied by a public project. The project was a Polish version of Ivekovi?’s ongoing project Women’s House (Sunglasses) in which she appropriates advertising for sunglasses in an effort to tackle the issue of violence against women.

Katarzyna Pabijanek: My first question concerns the Women’s House (Sunglasses) project you started in 1998. It has just been shownat the Muzeum Sztuki in ?ód? (Practice Makes the Master, curated by Magdalena Zió?kowska). Could you say something about the background of the project and, especially, about its current Polish version?

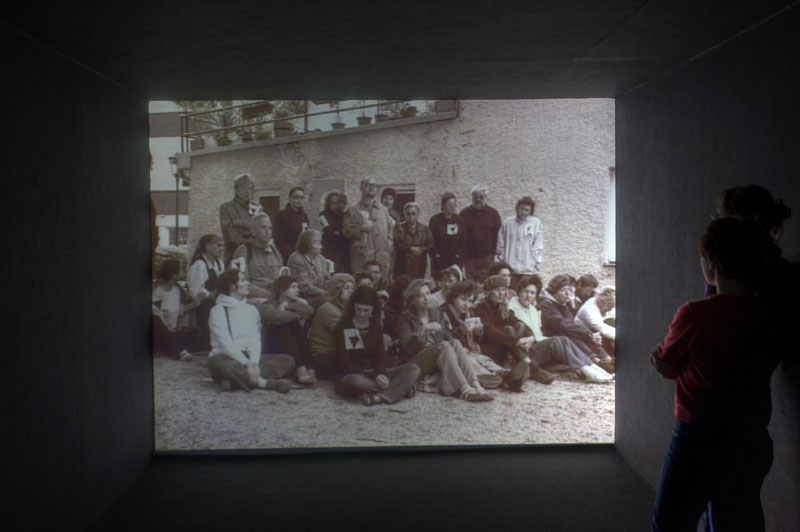

Sanja Iveković: The series produced for the show is a collaboration with the Federation for Women and Family Planning, titled Women’s House (Sunglasses) and is indeed a part of a bigger project. Women’s House deals with violence against women, an issue that was still a hidden issue in Croatia when I started to work on this topic. I myself learned about it at the Centre for Women’s Studies (founded in 1995) where I was teaching contemporary women’s art. Some of the courses at the Centre were taught by women-activists who established the Autonomous Women’s House – the first shelter for women victims of domestic violence in Eastern Europe. The House started in Zagreb in 1989 when a group of women squatted in an empty apartment and turned it into the shelter. I visited the shelter and it turned out to be an eye-opening experience for me. I decided to do an art project that would make this issue visible to the general public. I also wanted to develop a new type of work, one in which women who experienced violence were not just my artwork’s subjects but rather its active participants. It took me some time to find a method that would be easy, fast and cheap so that that the piece could be produced by the women in the shelter themselves. In the end I opted for a process that included a workshop in which we produced plaster casts of the women‘s faces, along with short life stories the wrote themselves. Then the „masks“ and texts were installed in accordance with specific exhibition spaces, either indoors or outdoors.

KP: And how did you decide to turn your project into an international cycle of events, one that triggered a wide-ranging interrogation of women’s rights?

SI: I consider Women’s House a work in progress, a long term project. It was first exhibited at Manifesta 2–The European Biennial of Contemporary Art in Luxembourg in 1998 – and since then the I have collaborated on the project with the Autonomous House in Zagreb, the Fraenhaus in Luxembourg, the Bangkok Emergency Home in Bangkok, Safe House in Peje, Kosova, Casa per le donne in Genova, the Center for Women and Children in Belgrade, Vie-Ja in Utrecht, Mor Cati in Istanbul, and Federation for Women and Family Planning in Polish cities. The project started in Croatia and the war in former Yugoslavia clearly comprised the background of my interest in these stories. The sex industry in Bangkok is the background for the stories of the women there, but there is also the perhaps unexpected level of domestic violence in the wealthy liberal democracy of Luxembourg. You may say that the project bears witness to the continued and unceasing level of violence against women in our societies, West and East, North and South. Each case may have its own “local” character, but the “universal” is the violence. Violence against women is regrettably a “universal” – not in the sense of a “transcendent” characteristic – since the reasons for this violence vary hugely – but in terms of a common “universal” condition that women inevitably experience in patriarchal societies. We know that violence against women is not confined to any class, race or creed. In this work I wanted to redraw the “universal” in such a way that, even though we are witnessing particular cases we are forced to reflect on the values in our own culture and society rather than merely distancing ourselves from this problem as something that happens to “others” or in “other cultures”.

KP: How did you move from using the casts of real women’s faces to using anonymous images appropriated from advertisements? How important is it for you to use the appropriated image instead of images of women who actually were victims of domestic violence? How is this related to the attempt to take these women out of the private space and make their experience public?

SI: I am very conscious of the context in which I am exhibiting. In the context of the museum or a gallery space, I find the installation to be the most appropriate form. The plaster “masks”, placed on pedestals and accompanied by the texts of the women’s stories, consciously mimic the installations one still finds in ethnographical or historical museums, where artifacts from different cultures are displayed. My motivation is to re-introduce real women from our society, who are often treated in a way as the “Other”, into public discourse. By situating this installation in a museum, I also question the role of the museum as an institution more generally, and the ways in which it functions. Though art galleries and museums are also public places, I find the mass media to be the most suitable vehicle by way of which to involve the general public. The media’s role in shaping dominant cultural representations should never be underestimated. That’s why it is important for me to use other media, such as posters, advertisements and billboards. I appropriate media images because my intention is to subvert the assumptions implied in the discourse of the mass media using its own language. This is not a new strategy, of course. It has been used by activists and artists for a long time. In the 90’s, when I became intensely involved in the activities of women’s NGOs in Croatia, I helped create a number of campaigns which were conceived by a coalition of women’s groups that involved producing posters, leaflets, and TV commercials. My experience as a graphic designer definitely did help me here.

SI: I am very conscious of the context in which I am exhibiting. In the context of the museum or a gallery space, I find the installation to be the most appropriate form. The plaster “masks”, placed on pedestals and accompanied by the texts of the women’s stories, consciously mimic the installations one still finds in ethnographical or historical museums, where artifacts from different cultures are displayed. My motivation is to re-introduce real women from our society, who are often treated in a way as the “Other”, into public discourse. By situating this installation in a museum, I also question the role of the museum as an institution more generally, and the ways in which it functions. Though art galleries and museums are also public places, I find the mass media to be the most suitable vehicle by way of which to involve the general public. The media’s role in shaping dominant cultural representations should never be underestimated. That’s why it is important for me to use other media, such as posters, advertisements and billboards. I appropriate media images because my intention is to subvert the assumptions implied in the discourse of the mass media using its own language. This is not a new strategy, of course. It has been used by activists and artists for a long time. In the 90’s, when I became intensely involved in the activities of women’s NGOs in Croatia, I helped create a number of campaigns which were conceived by a coalition of women’s groups that involved producing posters, leaflets, and TV commercials. My experience as a graphic designer definitely did help me here.

KP: Producing material that is distributed outside the gallery space makes the works more democratic and accessible. What kind of feedback have you received on these pieces?

SI: Well, it is difficult to say. It is not a performance, there is no round of applause at the end to let you know whether it’s working or not, and if so how well. In the case of Sunglasses it is not so easy to measure the feedback. Some people like it, others will criticize it. Being an artist who tries to also be an activist, I am eager to disseminate the message that there is violence against women, that there are legal problems related to this, and that something must be done about this. On the other hand, as an artist, I cannot allow myself to be conditioned by the feedback. I strongly believe in what I am doing, otherwise I wouldn’t do it. I have found that aesthetics are inseparable from politics. I must say that on a few occasions I had to disagree with the activists who commissioned a work from me. They thought that my proposals would not “work”, because my visuals were too “ambiguous” or they didn’t contain enough straightforward information, while I considered some of the material they produced not visually interesting at all. The position of an artist differs from that of an activist, but rather than separating the two activities, we can see them as circles of human activity that overlap in a relatively small area, and that is the area in which I try to do most of my work.

KP: What is a typical reaction to the posters from the Sunglasses series? Are people actually aware of the “double manipulation” you perform, based on re-appropriating the images from advertising and changing their meaning from a commercial to highly politicized one?

SI: When a person sees one of the Sunglasses posters, I think that she or he will at least be puzzled, initially. And this moment of puzzlement means that the work is communicating. We are surrounded by media messages and nowadays almost everybody is quite media literate and everybody is equipped with the tools with which to read this work. I might say that young people, in particular, who are mostly the target of media manipulation, respond in a very positive way to my works, because those images are very familiar to them. Of course, the media nowadays are so strong that there is the danger that they will absorb any image, any text, any subject. I am aware of this. But I also hope that I am correct in saying that a fashion company would never be willing to put the story of an abused woman over an image the purpose of which is to sell an expensive product, such as sunglasses.

KP: The rationale behind the project as a whole and behind the previous versions (in Croatia, Italy, Thailand and Turkey) was to tackle the issue of violence against women. However, in Poland, you decided to talk about abortion. Why this change? You know that the problem of domestic violence exists here as well. Does your decision to replace domestic violence with abortion imply that you perceive the lack of access to safe and legal abortion as a kind of violence?

SI: I come from an ex-communist country and at the time when Croatia won its independence and democracy was established, the first government was a right-wing conservative government, and one of its first tasks was to illegalize abortion. I remember myself being part of the coalition of women’s groups who started a fierce and hard fought campaignagainst its initiative in 1995. We were working days and nights trying to collect the signatures on our petition. Under communism, legal abortion was a basic right and we had never considered the possibility of losing it. Having personally experienced this terrible moment when the threat of losing this right was real, and being aware of the situation in Poland, I felt compelled to deal with abortion for the work that was being produced there. This is the way I normally operate; in every country where I am invited to work, I try to take the local socio-political context and use it as material for my work. But to return to the question if a lack of access to abortion is violence: yes, I do think it is, there’s no doubt about it. The illegalization of abortion is a violation of the basic human rights enshrined in the CEDAW and other UN documents. The right to a free choice is a basic right of all women.

KP: You made works such as SOS Nada Dimic and Gen XX to direct public attention to the mechanisms regulating public memory. In Utrecht you proposed renaming a street to honor an “unknown heroine“.

KP: You made works such as SOS Nada Dimic and Gen XX to direct public attention to the mechanisms regulating public memory. In Utrecht you proposed renaming a street to honor an “unknown heroine“.

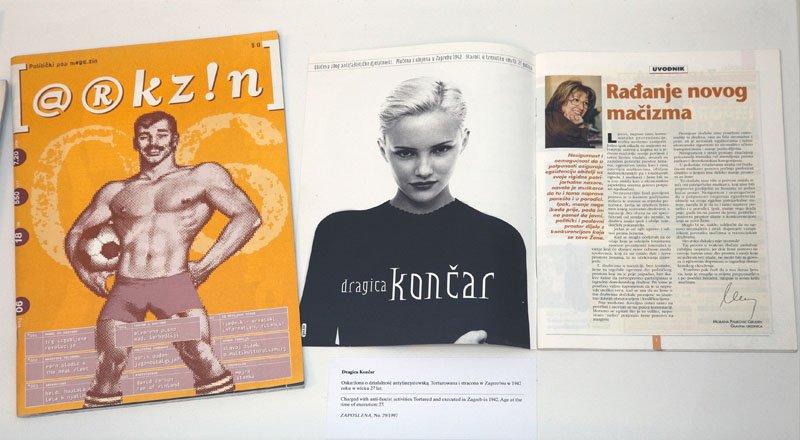

SI: It looks as if Utrecht’s mayor will agree to make this happen. As far as Gen XX is concerned, that project also involved the appropriation of media images. I erased the brand names from famous brands such as Dior, Chanel, Armani and replaced them with names of women who were heroines of anti-fascist movements. These were real women who were very well known to my generation and were considered national heroines in socialist Yugoslavia. At that time companies were given the names of these women in order to nourish public memory. After the shift to democracy a nationalistic discourse became omnipresent, promoting total amnesia regarding socialist era. As a result, these women have been erased from public memory. I was shocked to find, in my daughter’s schoolbook, not a single mention of them. I felt that I had to do something about this. Women who played important roles in history are so easily forgotten.

KP: Is it true that the issue of women being erased from public memory will return in your most current work?

SI: I am currently doing the extensive research for a project commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw. I would like to deal with the role played by women in the Solidarity movement. Not many people, especially outside of Poland, know that Solidarity was actually saved by women at the time when martial law was imposed in Poland, a time when men were unable to continue their underground work. In other words, women brought freedom to Poland. Yet when democracy came, few of these women were given leadership positions in Solidarity, and it is not far from the truth that today these brave women who defeated communism in Poland have all but dissapeared from public memory. My biggest wish is to build a monument to these invisible women of Solidarity.

KP: On the one hand you deal with women who were erased from the public memory; on the other hand, you raise the question of the many unknown, anonymous women whose work was never acknowledged…

SI: I do believe that it is not only important to put the name of the women who were once famous back into our consciousness; we also need to remember that the engagement of a large numbers of anonymous women was essential in building the world we live in today.

KP: Why doyou involve social organizations in your projects? What kind of influence does this have on your work and its dissemination?

SI: I collaborate with activist organizations because I think that they offer efficient models of production that can expand the rather confining borders of the art world. It’s not only a matter of empowerment, but also of the wish to encourage a fertile dialogue between activities that, lamentably, generally remain quite far removed from one another–art and activism. I try to be critical towards my own role, so I refrain from giving my view on issues I don’t know much about, preferring instead to leave their presentation to those who are immersed in them. But I am also ready to fight for a visual language of my own, the one I consider best suited to give shape to the project, in order to establish communication with the public and create greater visibility for a given project. I started my artistic career in 1971 and my art naturally changed over time. In the 70s, when I was living in the former Yugoslavia, I produced various works dealing with the power structures typical of the kind of socialist society I was living in. By 1989 everything had changed and I felt that new modes of operation should be introduced into my art practice. It was challenging for me to think about art that could be still critical but also participatory. Instead of being limited by traditional ways of merely illustrating the political context, I was searching for the method that would have the strongest possible impact on real life.

KP: You mentioned the shift that accompanied the transition from communism to democracy. However, it seems that all of your art has had a very strong common denominator. Many of your early works deconstructed the way society and mass media influence femininity, while subsequent work debated the position of women within the context of communist public space (Triangle). Your current work openly campaigns for women’s rights. No matter how problematic it may be nowadays to call somebody a feminist artist, it seems that feminism has always fueled your work. Indeed, you were apparently the first Croatian artist to call herself a feminist…

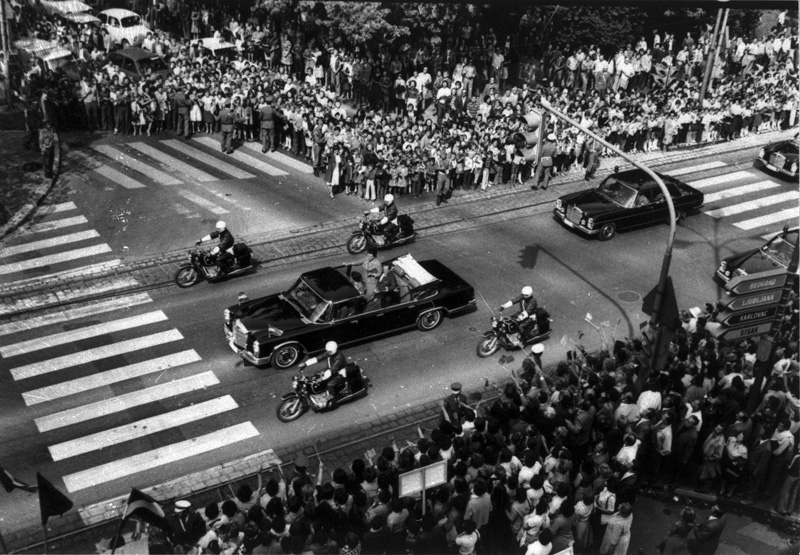

SI: Lucy Lippard once offered a simple definition of feminist art–everything that a feminist does, she said, is feminist art. This explanation was a witty rewriting of the kind of explanation often used by the first generation of conceptual artists (mostly men at the time) to define their work–everything that an artist exhibits is art. Personally, I try to avoid the limited range of categories used by some critics. Feminist issues interest me but this doesn’t mean that I walk around shouting: Hi, I’m a feminist! My work is feminist, but at the same time it is post-conceptual, postmodernist, activist, socially engaged….When feminism was introduced in ex-Yugoslavia I was already an established artist so I guess it was easier forme to openly say that I was a feminist. Already in 1978, the first international feminist gathering (the first in a socialist country!) had been organised at the Belgrade cultural centre by women from Ljubljana, Zagreb, and Belgrade, under the title Comradesse Woman: The Women Issue? This was a turning point for feminism and for the history of civil society in Yugoslavia. The Women’s Section of the Sociological Society of the University of Zagreb was formed in Zagreb that same year under the title “Woman and Society”, providing an arena for a systematic engagement with feminist theory. Although I was a personal friend of the members of the Section and attended their lectures, their research did not include visual art. The language of visual art simply wasn’t recognized as a relevant discourse yet. At that time I was frequently asked whether I was a feminist. “I am. Are you not?” was my usual answer. It just seemed so natural and unproblematic to make this kind of declaration at that time. Calling myself a feminist was a gesture of disobedience toward the communist regime that treated feminism as a bourgeois import from the West. Communism didn’t deal with equal rights—the discourse of equal rights was just a thin layer covering the very stable patriarchy, that had been in place, remained in place at that time, and continues today.

KP: How has the position of women changed since the beginning of your practice in the 1970s?

SI: Things are definitely improving: we have a committee for gender equality in the government and a strong women’s rights organization that is becoming more and more influential. Within the art world I happily observe the great number of emerging women artists whose work carries strong messages. It is not really possible anymore to do a group show without having a number of women included. In fact, my opinion is that presently women artists are the art world’s most powerful contingent. It is interesting to note that recently we have experienced a sort of revival of 1970s ideas, including feminist art. It would be tempting to ask why we are currently dealing with a revival of feminism and feminist art? Bojana Peji?, the curator of the Gender Check show in Vienna wrote an essay entitled “Why Is Feminism Suddenly So Sexy Again?” Her main point comes at the end of the essay when Pejic argues that the real question is not why feminism is sexy again but why we forgot about it in the first place.

SI: Things are definitely improving: we have a committee for gender equality in the government and a strong women’s rights organization that is becoming more and more influential. Within the art world I happily observe the great number of emerging women artists whose work carries strong messages. It is not really possible anymore to do a group show without having a number of women included. In fact, my opinion is that presently women artists are the art world’s most powerful contingent. It is interesting to note that recently we have experienced a sort of revival of 1970s ideas, including feminist art. It would be tempting to ask why we are currently dealing with a revival of feminism and feminist art? Bojana Peji?, the curator of the Gender Check show in Vienna wrote an essay entitled “Why Is Feminism Suddenly So Sexy Again?” Her main point comes at the end of the essay when Pejic argues that the real question is not why feminism is sexy again but why we forgot about it in the first place.

?ód?, October 18, 2009

A fragment of this interview was published in Polish in Wysokie Obcasy (05.12.2009) under the title “Her High Noon”.

The interview was possible thanks to the courtesy of Muzeum Sztuki in ?ód?, www.msl.org.pl.