“Girl Getting Into a Hole”

Agata Bogacka, I’m bleeding!, Ujazdowski Castle, Warsaw, June 2003

|  |  |  |  |

A Girl Getting Into a Hole is the title of one of the paintings by Agata Bogacka. During her first individual exhibition I’m bleeding! , organized this year in the Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw, the painting was hanging on a side wall at the very back of the exhibition room.

Yet, this inconspicuous work can be seen as creating a kind of frame for the exposition and, more generally, Agata’s oeuvre.

This is so because her paintings seem to be statements made by a “naughty girl” who constantly slips away showing the viewers, or maybe the world itself, her backside.

She emerges from this hole whenever and wherever she wants and only then displays bits and pieces of her experiences.

Agata’s work might be thought of as the autobiography in painting. It is not, however, a multi-plot novel, but rather a collection of brief notes.

They compose some story but know it only in an incomplete form. They are like stills from a film recording her life: single moments, memorized and transformed.

This association with film seems justified as Agata takes photographs when planning her paintings – what she remembers is preserved in a form of arranged scenes of which she takes photos then transformed into paintings.

She transforms them in a specific way as not all that the camera has registered is depicted in her work.

Agata concentrates on people and turns everything that surrounds them into a gray or beige unified background with only a few particular objects in view.

The people depicted seem to be floating in space and time, by which she aims to achieve a distance from what has happened.

These depictions result in pictures that do not, to a certain degree at least, convey information of real everyday life but rather speak of moods and changes in the author’s mood.

Her autobiography cannot be thought of in terms of an auto-portrait, if we think about the latter in traditional categories.

Even when a mirror, and Agata’s own reflection in it, become central elements of the painting they do not attempt to present the “self.” This already becomes clear in a painting placed at the entrance to the exhibition In fact, the youths are realists.

In it Agata showed herself barely dressed in a T-shirt, sitting in front of a mirror with her legs spread.

We cannot see her face and the intimate parts of the body (at which she is looking) in either the mirror or in the space before it.

This composition, seeming to invite the viewers to join the artist in her contemplation of herself, suggests rather that any attempt of hers to approach her own “self” includes the relationship with the others.

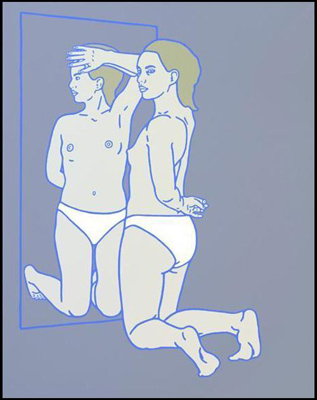

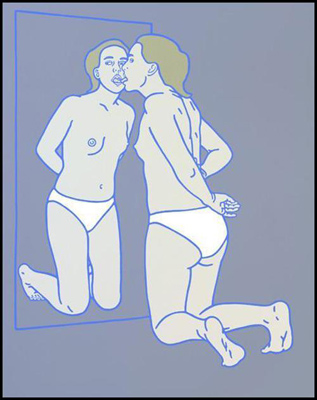

In two of Agata’s other paintings she is kneeling in front of a mirror, yet not looking at herself but at the viewers.

In the first one, Mirror I, she kneels as if waiting for reaction; in the second, Mirror II, having got, as we may guess, no response, starts licking the reflection of her face.

There appears a love relationwith herself but with the aim of provoking others.

If one observes the media reactions to Agata’s work it seems that the aim has been achieved (although through these paintings it was not the media, but a single viewer, who she wanted to provoke).

It was of special significance that Agata entered the art world with a series Agata (painted in 2001) in which she has showed herself in the company of three men just a moment after sexual intercourse.

Someone somewhere wrote that she is “a girl from a big city” and since then it is her social and intimate life that interests the media and her works are read in the context of the series “Sex and the City.”

Agata does not object to being perceived in this way but it is clear that something is missing in this image.

What is usually overlooked is the overwhelming feeling of loneliness that seems to me to be characteristic for Agata’s picture of the condition of a young woman that could be seen during the exhibition.

The multiplication of one’s image not only makes it possible and easier to relate to oneself but also makes this particular relation to be the most important. However, in the case of this artist it is not simply an expression of feminine vanity.

Nor does it mean that Agata rejects her (feminine) position of an object to-be-looked-at: she is both a creative subject and an object of her own interest in constant oscillation between the two.

She is both desiring and desired. She knows she is attractive, appreciates it and knows how to use it in a sort of game with others-a game that does not lead to happy endings.

The desire to establish close contact with the others and the inability to achieve it is a theme constantly present in Agata’s paintings.

Her relationship with her brother and his pregnant girl-friend are the closest and most tender of all, which is clearly visible in the paintings showing them together, yet it is marked with a sense of loss.

In the picture showing Agata and her brother, Leave-taking, gestures are stopped half-way, the moment is seized and shown with the awareness that nothing is going to be the same anymore.

What is left is serene acceptance of the situation and the new person between them, the girl who seems to be blessed by Agata in another of her works, Visitation. The one who is the nearest person to her – her brother – is leaving, longing remains.

She places herself and all other characters in an empty space, which evokes the feeling of loneliness.

When I write “evokes” I have in mind contemporary categories of aesthetics of melancholy as they were defined by Susan Sontag.

She emphasizes that melancholy can be expressed through ambiguities, paradoxes, and inconsistencies. It appears in works of art through a kind of unsolvability. Play best friv games site.

In Agata’s paintings it expresses itself not through symbols but on an iconic level – in a structure of the picture.

The people in these paintings, even though in motion in the original photographs, remain still; Rather passive than active.

The world is at (a) standstill. Nevertheless, a slightly dramatizing move, which is hard to notice at first, connects her paintings that usually come in two.

They are records of two moments between which something has happened: somebody has made an only seemingly unimportant gesture.

It becomes clear in the end, however, that whatever action one could undertake, the situation always remains unchanged.

According to psychoanalysts, melancholy is linked to women’s position in the patriarchal culture.

Becoming a part of the symbolic order they must lose a part of their primary love to their mother, which is an act of giving up a part of the “self”: a mother-slaughter-suicide.

A feeling of loss and lack of unity results in constant anxiety. Women try to make up this feeling of loss, but the objects they desire are never the right ones.

There is always a gap, some distance between the loving desire and its object, making fulfillment impossible. Everything is at a standstill, inert due to the feeling of impotence.

This experience seems to be the enduring motive of Agata’s work. Multiplication does not exclude emptiness but seems to magnify it.

With subsequent meetings, Agata hopes to face something that would fill in the gap and suppress her loneliness, but she fails.

Consecutive contacts are a repeated ritual of superficial relationships and each time proves that nothing changes.

It makes men disappear from her work – they are scarcely present at this exhibition (it is her image that predominates). At least real men, ones as in A Man Who Wasn’t There make, an appearance.

A Man Who Wasn’t There – the painter’s vision, her answer to disappointment following every effort at creating bonds.

This is not the only attempt to surpass the overwhelming mood of melancholy that can be seen in this exhibition. There is clearly something happening in her new paintings.

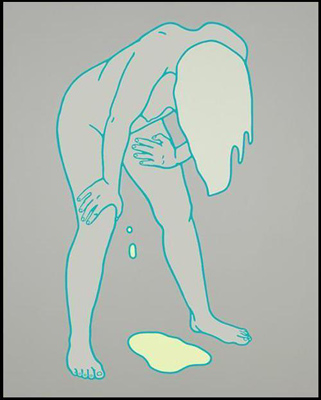

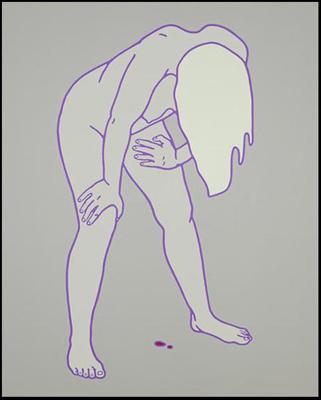

One could literally say that Agata comes back to life. There are two new elements, two physiological liquids: blood and urine defining her as a living being.

I’m bleeding! she states with a degree of astonishment, as if she has suddenly become aware of her own vital functions, aware of the inner rhythm existing independently of recurring unhappy relationships, of efforts undertaken time after another to come closer to others accompanied by a growing distance.

Her recent work is a means to address herself, this time not through a mirror reflection but through her own body and the processes within it.

Blood, especially menstrual blood, is usually thought of as a pass to femininity, a symbol of the power and the potential of a woman’s body.

It is also, in our culture, seen as something dirty, embarrassing that should be put away out of sight. These contradictory terms reflect, in my opinion, the status of blood and urine in Agata’s work.

I’m bleeding! is also an outcry addressed to somebody, a wish to draw somebody’s attention. In this context the use of the above mentioned fluids might turn out to be a trick.

The supposed blood pouring out of her mouth may be blackcurrant juice from the box she is holding. Drops on her thigh may be of the same origin.

It is a kind of simulation, where becoming alive is a mere illusion or maybe a wish, just like the one in The Man Who Wasn’t There.

In these paintings self-irony can be clearly seen – a degree of distance from herself sometimes mixed with narcissistic self-contentment characteristic for Agata’s oeuvre.

Laughter (that is not carefree and serves to cover up the discomfort) and pain merge in these paintings.

Agata’s “autobiography in painting” is certainly a confession. It is a diary through which she attempts to recognize and reveal her relations with others as well as the accompanying emotions; she seems to work through her relations with others and constructs her own identity.

It is done however in full visibility of which she is not only aware but turns into a game. All the paintings have been hung low in such a way that it is necessary for the viewer to come into “physical” contact with her.

The viewer cannot be a voyeur here as when looking at her intimate world; he or she is faced with Agata’s look.

The promise given by the work opening the exhibition is not fulfilled – we are not able to fully enter her private world.

She plays with the media showing a lot, but simultaneously, when it seems that she can be caught, she escapes and “gets into a hole” (Little Girl Getting Into A Hole).

Agata becomes just like a little girl described in contemporary feminist texts – a figure of a person that cannot be restrained.