Interview With Eszter Lázár

Eszter Lázár studied art history and cultural anthropology at ELTE (Eötvös Lóránd University, Budapest) and has been working as a curator at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts, where she is a leading member of the exhibition committee. She also works at the Karton Gallery in Budapest. Her writings have been featured in: Balkon, exindex, Muérto, Magyar Lettre Internationale, and various exhibition catalogues. ELTE has two major exhibition spaces, and since her arrival as curator, the exhibition profile of these spaces has changed considerably; rather than staying on the margins of curating practices, Eszter Lázár has injected a new vitality, which will undoubtedly impact the entire Budapest art scene.

Allan Siegel: It seems that here the task of the curator is becoming more and more important; it is no longer fixed to the pedagogy of art history. How do you see curating?

Eszter Lázár: We should make the term “curating” a bit more specific to a region, aswell as each country within a region. There are curatorial courses, for example, in Slovenia and Poland. But the difference is not only in education. I think this is a kind of “site-specific” term, and only in certain cases can one use this word to articulate curatorial practice in Hungary.

There are institutes (museums, galleries, non-profit spaces) where curators have important positions, but the institutional background always gives a rigid kind of structure where one can hardly realize things one imagines. You have to be inventive and deal with institutional-structural issues in order to adapt the post-socialist system to your visions. The system of the cultural field and the lack of a proper market (as well as the financial situation) do not really support freelance curating, although this could establish a healthy competition.

Some university programs in Hungary are planning to start curatorial courses, which is a very welcome development. Hopefully the effects will be felt soon in cultural productions and exhibitions and this will also create a fruitful discussion.

Some years ago an association called CAB (Curatorial Association Budapest) was founded. It was initiated by a group of curators and an artist in Hungary. Although it was a very important initiative, unfortunately, the association is not really active anymore.

A.S.: Since the CAB is no longer active, has it been replaced another network or group?

E.L.: Hungary is a small country; instead of “network” I would use the word “acquaintances.” Acquaintances help each other in realizing projects (both in a practical and theoretical sense) or, importantly, share their knowledge and experiences in thinking about / imagining exhibitions. I have received great support from curators, but they are, first and foremost, my friends. I suppose the CAB I mentioned before had the creation of a kind of network as one of its aims.

If we examine this phenomenon in a broader context (in the CEE or other countries), one can talk about networks that were built based on common projects and that seem to function in the long term as well.

A.S.: Did you study curating or art history?

E.L.: Art history. There is no curatorial course in Hungary. All of the curators – except some who studied abroad – have a background in art history or maybe literature or aesthetics. I studied art history and cultural anthropology at ELTE.

A.S.: Isn’t this a problem?.

E.L.: Yes, it is. Here you really have to find your own way, your network and perception about how to curate or organize a show. But the curatorial course that the Hungarian University of Fine Arts is planning to start in 2009 will probably make a great difference in this respect.

A.S.: Here the whole idea of being a curator is relatively new.

E.L.: The term requires definitions that have been changing all the time and accommodating shifts in paradigms that exist in an expanding field. It also causes curators to be seen as fulfilling an institutionalized role. A curator has to have both theoretical background and practical knowledge.

A.S.: Well, there is a logistical definition relating to organizing and then another that relates more to what we were talking about earlier, which is really about working with themes and concepts.

E.L.: This is the definition I prefer.

A.S.: There is a big difference between working with current theoretical discourses and just hanging a show (not that that doesn’t take skill or knowledge). But the second area is more interesting for me as well; how do people respond to this perspective here?

E.L.: It is very important where you do the show; here at the university, the tasks are different from those at the Mucsarnok / Kunsthalle Budapest. Some of my colleagues really appreciate my activities here because, in their opinion, the exhibition profile has been changing, which is very important for the whole art scene. We try to be the initiators of new dialogues and to involve the school via projects in current discussions and dialogues about exhibition making, education, etc.

A.S.: Can you tell me about the background of these recent exhibitions? How it was working with people outside of the country and the networks you developed?

E.L.: I have been working at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts for years as a member of the Exhibition Committee. The Hungarian University of Fine Arts, instead of making more partnerships in Western countries, is focusing on the region and on the Eastern European and Post Soviet states. The university curriculum and the usual financial problems do not give for us or our partners a chance to go much further than these first official steps. So one or two years ago I decided to curate a show based on contemporary art from the Post Soviet states. The curatorial workshop for professionals from Eastern Europe and from the Post Soviet states held in Armenia, where I went in summer 2007, was very important and useful to realize the project.

A.S.: Something must have motivated you to try and put this together?

E.L.: The Hungarian University of Fine Arts, instead of making more partnerships in Western countries, is focusing on the region and on the Eastern European and Post Soviet states. In these past few years the Rector signed contracts with Fine Art Universities in the Ukraine and Azerbaijan. The university curriculum and the usual financial problems do not give for us or our partners a chance to go much further than these first official steps. So one or two years ago I decided to curate a show based on contemporary art from the Post Soviet states. The curatorial workshop for professionals from Eastern Europe and from the Post Soviet states held in Armenia, where I went in summer 2007, was very important and useful to realize the project.

A.S.: Was there a thematic idea?

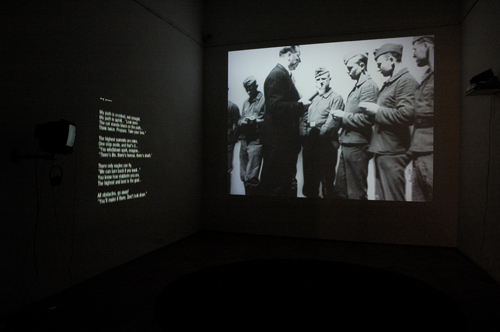

E.L.: The concept of the show is how the historical past and memories affect the present. The traces of history can still be read in the present tense in Post Soviet countries. The effects of the historical past (communism) can be sensed in everyday life here in Hungary as well.

A.S.: For the Satellite Tunes exhibition, where did the artists come from?

E.L.: The exhibiting participants include freshly graduated university students for whom the Soviet Union means something entirely different than to those artists who personally experienced the various phases of the period preceding the changes. Besides the already established artists (Arturas Raila, Chto Delat group, Aleksander Komarov), it was extremely important for me to choose young ones – for example, the RES group from the Ukraine who are still at the academies or recently graduated. The works on display were created in the past few years (2002-2008).

A.S.: Satellite Tunes seems to follow from an earlier exhibition you did?

E.L.: Yes, I am interested in how you integrate past events, materials, or archives within a contemporary context. I made a similar show two years ago – “Intimations of the Past,” which featured the works of artists like Chantal Akerman, Anri Sala, Adrian Paci, Anna Konik, Luca Gobölyös, Tibor Gyenis, Pál Gerber, and Mario Rizzi. The Hungarian artists were given the possibility to make new work for the show. The topic was similar. The Post Soviet show could be thought of as a second phase of this theme.

A.S.: The lastshow seems to be about creating work that becomes memory.

E.L.: In “Satellite Tunes,” I was really interested in how young artists work with the past, memory and historical background such as communism and the Soviet Union. Of course, it is a huge region, but I tried to focus on the relationship of the collective to the personal past—it sounds like a cliché, but that is how it worked. I tried to start with my own experiences from Communist Hungary; when I was a “pioneer.” I’m not a historian so I don’t think I have to treat these things only in a historical way. I selected works which have a feeling or express this theme.

A.S.: Since the “changes,” how have Hungarian artists approached the past? Has it changed since 1989 through the present?

E.L.: Hungarian artists seem to treat this topic with a degree of uncertainty, which could be interpreted as a form of aloofness in connection with the political and historical past.

It is a very well researched and discussed topic internationally.

A.S.: The whole question of memory.

E.L.: Yes, the question of memory, but I wouldn’t say that it is very significant here. Although it is very important—we have a different relationship to the past. Memory studies are very important but they belong more to the realm of academic discourse and also the setting where party politics scenarios are played out with symbols and concepts without the aim of coming to terms with the legacy of WWII and communism / Kádárism. This is somehow subject to avoidance and sophistry in art and becomes stronger in literature. Although historical research has begun, only a smaller circle of historians and art historians is familiar with it.

There was an exhibition series in Budapest. The AICA (Association Internationale des Critiques d’Art) organized workshops, symposiums, and exhibitions and there were different venues. I was asked to curate a program related to the theme “Exposed Memories: Family Pictures in Private and Public Memory.”

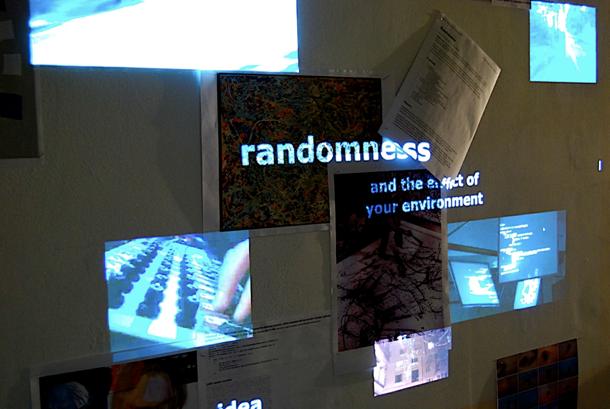

A.S.: For Visibility Works, was the process different?

E.L.: This was different and more difficult than the first, because I integrated the workshop system into the exhibition. But it was easier in terms of the financial aspect since it was organized within the framework of the LOWFEST (Dutch Flemish Festival). So I had support from the festival, I could travel to Amsterdam, meet artists, select topics and extend an invitation to them.

A.S.: I think the exhibitions here are very relevant to a new generation of artists; the Kunsthalle Budapest fulfills a different kind of function.

A.S.: I think the exhibitions here are very relevant to a new generation of artists; the Kunsthalle Budapest fulfills a different kind of function.

E.L.: This is true. In the past, people didn’t really pay much regard to university exhibitions so—with my colleagues—we decided to gradually change the profile of the Barcsay Hall. We had shows in the past but we did not really have an exhibition profile per se. In that sense, from almost nothing we were, hopefully, able to create something. It has been both difficult and challenging at the same time.

When you work at the Kunsthalle Budapest, there is the legacy of diverse expectations fueled by political and ministerial pressure, by the size of the building, its representational capacities and still oversized team.

A.S.: It is important to have this kind of laboratory where you can work with these emerging discourses.

E.L.: I try to introduce and enhance discussion and thinking, integrate the current discursive practices and information… we are at the very beginning of building up a different kind of education and exhibition making practice inside the University. I do not know what effect my previous and current projects have among the students.

A.S.: That is difficult to know because sometimes you cannot really tell the impact or influence until much later.

E.L.: Dóra Hegyi has written an article about “Visibility Works” on the Tranzitblog (http://tranzit.blog.hu/), and I was very pleased because she made a link between one of my previous projects “Models for a Fictional Academy” (2006) and “Visibility Works” in relation to institutional criticism and pointed out that in the latter we took a step further by inviting Dutch artists to create work related to this topic and work with students.

A.S.: Is there a problem with how students here engage with similar students (or guest artists / professors) from outside the country?

A.S.: Is there a problem with how students here engage with similar students (or guest artists / professors) from outside the country?

E.L.: After all, our task is to initiate and create an environment where they can gradually get to know discourses, theories, etc. We need to invite more people from outside for workshops, facilitate communication in English, and support platforms for arguments.

Budapest, 23 February 2008.