Wild Recuperations: Material from Below and D’EST, Chapter 6: ReTopia at District Berlin

WILDES WIEDERHOLEN. MATERIAL VON UNTEN ARCHIVE OF GDR OPPOSITION, HAUS 22 STASIZENTRALE AND DISTRICT BERLIN, NOVEMBER 4 – DECEMBER 16, 2018.

D’EST SCREENING, CHAPTER 6: RETOPIA, HAUS 22 STASIZENTRALE, BERLIN , DECEMBER 15, 2018

Attempts to establish contemporary archives must always contend with dominant history and ideology. Wild Recuperations. Material from Below, a six-week-long exhibition that took place at District Berlin and the Archive of the German Democratic Republic’s (GDR) Opposition in late 2018 and continues today as an ongoing artistic research project, positions itself firmly against the ossification of objectified knowledge by introducing an artistic and affective approach to the archive.

The Archive of the GDR Opposition, located in Berlin-Lichtenberg, houses a wide collection of materials from former GDR’s dissident groups: the so-called Citizens’ Movements (Bürgerbewegungen), including the environmental, feminist and queer, human rights, and peace movements that operated from within and against the GDR’s state socialism. Established in the early days of post-reunification by protagonists of these opposition groups, the Archive catalogs the unique political and social practices of the GDR, most of which were virtually erased from historical memory after the Fall of the Berlin Wall.

Elske Rosenfeld, Installation view of “A Vocabulary of Revolutionary Gestures: Interrupting: A bit of a Complex Situation,” video installation at wild recuperations. material from below, District and Archive of the GDR Opposition, 2018. Photo by Emma Haugh.

Taking the GDR Opposition Archive as its formal backdrop, Wild Recuperations was embedded in and dispersed throughout the Archive’s typically drab, bureaucratic landscape. The exhibition invited contributing artists to pull from the available archival materials and artifacts and interact with them artistically. These interventions—often on paper, audio or video, like the archival materials themselves—blended with their surroundings. As each work was presented alongside and in dialog with an artifact from the collection of the GDR Opposition Archive, to an untrained eye it was hard to tell them apart.

With this non-invasive exhibition concept, curators Elske Rosenfeld and Suza Husse managed to perform a deft subversion “from below” on a visual level as well as a conceptual one: the exhibition title and its subtle presentation suggested a tweak or minor disruption that attempted to envisage another reality or truth beyond the one that is rapidly becoming institutionalized. Using the visual language of the institution itself, the curators and contributing artists wove their own affective interpretations of historical artifacts seamlessly throughout the space. One room—perhaps a meeting room, indistinguishable from the office spaces used by archivists and administrators—presented a series of interventions and zines laid out on a long table, to be perused at visitors’ leisure. A Walkman and headphones on a small side table played an audio piece by members of the collective Raumerweiterungshalle. During their research in the Archive, members of the collective Ernest Ah, Sabrina Saase and Lee Stevensproduced a radio play reflecting on lesbian and transgender realities, cultures and organizations in the former GDR and today.

Raumerweiterungshalle Collective: “gemeinsam unerträglich. ein dokumentarisches Mosaik”, zine and radio play; Nadia Tsulukidze, “Big Bang Backwards”, video performance and installation; both produced for wild recuperations. material from below, District and Archive of the GDR Opposition, 2018. Photo by Emma Haugh.

Since 1989, the GDR—a complicated and rich society—has often been vilified wholesale by dominant historical narratives and largely written off as a totalitarian surveillance state. Few wonder how this wholesale condemnation squares with the complex lived experiences of those who grew up inside the GDR or, for that matter, those who opposed its state apparatus and tried to change Socialism from within. Yet as many of today’s younger generations come of age in a unified Germany, the myth of a harmonious integration of both cultures seems increasingly far from their experience. The exhibition aimed to complicate the one-sided narrative of seamless reunification by bringing to light personal experiences and political ideas from the underground, opinions and political allegiances that were largely forgotten in the aftermath. In its press release, the exhibition considers “archival and historicizing practices themselves as a field of conceptual and aesthetic processing.” By working through and with the archive and questioning its sovereign language, the exhibition enacts a kind of analysis of aspects of the history of the GDR, of the 1989 revolution, and of the reunification period that have been left out of contemporary accounts.

The title of the exhibition alludes to the 1984 split-LP DDR von unten (GDR from Below) by GDR punk bands Zwitschermaschine and Schleim-Keim (Saukerle). The title describes the record’s long route towards its final release in West Berlin, as well as to the underground opposition. The latter included prominent alternative writer Sascha Anderson who was later disgraced as an informant, a figure whose presence appears throughout the exhibition. Berlin-based artist Henrike Naumann addressed the record, among other dissident cultural productions, directly in her performance piece BRONXX, which was presented on the closing weekend of the show. In it, Naumann and collaborator Technosekte developed an alternative communication system that questioned history as a ritual and used rhythm and drum beats to explore the possibility that experimental music can contribute to new forms of community. Dressed in fencing outfits, the members of Technosekte stood in an inward-facing circle, pounding out drum rhythms not unlike those found in tribal rituals, and alluding to the human-creature hybrid on the cover image of the DDR from Below LP.

Technosekte + Henrike Naumann: performance “BRONXX” at Haus 22/Former Stasi Headquarters produced for wild recuperations. material from below, District and Archive of the GDR Opposition, 2018. Photo by Emma Haugh

Though the room was pitch dark, an iconographic, semi-religious pattern was created in the space, using the beige boardroom chairs and coat racks from the building. Naumann is more generally known for her elaborate set designs, drawing from an extensive repertoire of post-GDR furniture and décor. She also confronts the right-wing extremism that has been so prevalent in the former GDR since the 1990s, making use of its symbolism and aesthetics in her work to defetishize it. There is always a danger that such reappropriation may appear flippant, especially given the current rise of the populist right internationally. However, Naumann’s work questions the formation of ideology by reusing and repositioning ideological visual languages taken from the now-kitsch world of retro furniture and accoutrements. It’s as if she had meticulously sifted through the flea markets of East Berlin, taking in everything from innocuous homewares to Nazi and Soviet memorabilia.

A 1989 print work by GDR dissident and artist Bärbel Bohley frames the exhibition entrance with the following text: “Manchmal ist Kunst abwesend” (“Sometimes art is absent”). The quotation is part of a longer reflection by Bohley about the inextricable relationship between art, politics and life. Rather than being a “political artist,” Bohley saw herself as a political person who also makes art; all of these identities should be understood as a whole, even when the art is absent. In Wildes Wiederholen, similarly, art was culled from seemingly straightforward forms of political documentation. As a result, there was little distinction between archival materials and art. Though perhaps disorienting for those expecting a more traditional art exhibition, the presentation had lasting conceptual effects: visitors were encouraged to consider the archive itself as a work-in-progress, even as a work of art or a fiction.

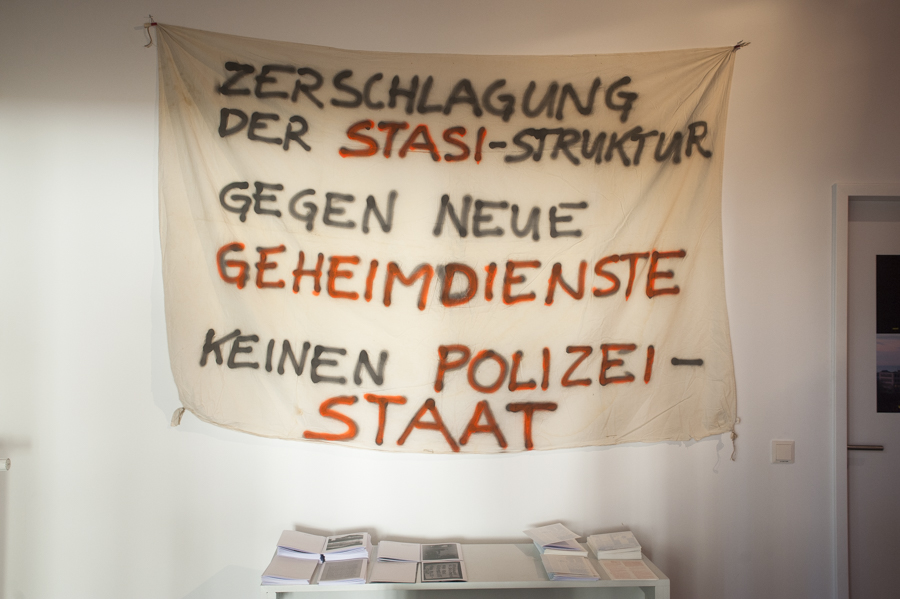

Banner from the occupation of the Stasi headquarters in 1990, selected from the Archive of the GDR Oppositon by Elsa Westreicher, installation view at District with zines produced for wild recuperations. material from below by Elsa Westreicher, Mareike Bernien & Alex Gerbaulet, Raumerweiterungshalle Collective (Ernest Ah, Sabrina Saase und Lee Stevens), Kai Ziegner, 2018. Photo by Emma Haugh.

The second part of the show took place at the District Berlin space in the suburb of Tempelhof. It was comprised of an installation by Leipzig-born artist Anna Zett and an accompanying archival artifact (a banner used in the occupation of the Stasizentrale, the headquarters of the GDR secret police), reflecting on the failures of language in describing the lived experiences of the former GDR. Zett took as her site the landfills that were an important factor in the East-West political relationship during the Cold War. It’s known that West Germany deposited a large portion of its waste in East Germany, in exchange for Western currency. Environmental opposition groups within the GDR were critical of the government’s willingness to accept garbage from the West (both literally and metaphorically), arguing against using the land commons for profit.

Zett maintains that a failure of communication existed between the two sides: the Communism of the GDR communicated through a state-sanctioned bureaucratic “dead language,” while Capitalism (the Federal Republic) preferred to speak numerically rather than through elaborate rhetoric, making discourse an economic commodity among others. In her video work Deponie (German for landfill), she painstakingly spray painted a love letter on the shifting ground of a gravel pile that addresses itself to the environment. “Liebe Umwelt,” the letter begins, “Es gibt da etwas, das ich loswerden muss” (“Dear Environment, there’s something I need to get rid of / get off my chest.”) In her letter, Zett reflects on the way these industrial spaces became ideological tools in the hands of both German states, and how their politicized nature went beyond their use value as garbage dumps, taking on metaphorical value as well.

Anna Zett: “Deponie”, installation at District, produced for wild recuperations. material from below, District and Archive of the GDR Opposition, 2018. Photo by Emma Haugh.

Zett’s two-channel video piece is made up of found footage from the archive. Seen here are videos of protests (using the same red spray paint found in Deponie), readings by underground poets, including Sascha Anderson, and interviews with GDR citizens about the reality of everyday life in the country. A young, black German living in Leipzig recounts her experiences of daily racism while cleaning the communal staircase in her building, rectifying the false impression that the city tries to create for foreigners by making it appear clean. Viewers could watch both works by Zett from atop a pile of gravel that had been placed on the floor of the gallery.

On the final weekend of the show, the project teamed up with the recently established contemporary video art platform D’EST to present the latest chapter of its own archival process. D’EST, a project initiated at District by cultural studies scholar Ulrike Gerhardt, maps out female collective positions that reflect post-socialist transformation, complicating any easy distinction between “East” and “West.” In its sixth installment (chapter), entitled ReTopia,invited curators Bettina Knaup and Katja Kobolt brought together six filmmakers and collectives to screen their works in a space located next to the Archive of the GDR Opposition, in the newly designated Campus for Democracy that was also used as a backdrop for Naumann’s performance.

According to Knaup and Kobolt, the selected video works, aimed to attend to “the wounds constantly re-opened by the violence of binarity.” To this end, the screening began with a piece by Croatian video artist Renata Poljak, entitled Staging Actors / Staging Beliefs (2012) that looked at a Yugoslavian propaganda film, re-enacting the heroic acts and untimely death of partisan child soldier Boško Buha during the Second World War. Poljak interviewed the young boy (now a middle-aged man) who had starred as Buha in the short film, asking him questions about the relevance of these political symbols today, and about his relationship to former Yugoslavia. The actor who played Buha responds to each question twice: once, reflecting a positive experience and nostalgic appreciation for his childhood memories; the second time, offering a common contemporary, right-of-center Croatian attitude that perceives Yugoslavia as a restrictive totalitarian regime. Hearing both perspectives spoken by the same person confronts the viewer with the complexity of the lived experience of post-socialist states, especially in relation to how they are perceived globally today. It remains unclear which opinion this former child actor truly holds.

Towards Memory (2016) by Kathrin Winkler returned the audience to the local setting of the GDR with a portrait of contemporary Namibia, a former German colony that maintained a “special relationship” with the GDR. From 1979, hundreds of children of Namibian refugees and political exiles were sent to East Germany for resettlement and education. Interviews with some of these “GDR-Children of Namibia” reflect the immense challenges they faced after 1989 when following the former German colony’s formal independence in 1990 they were repatriated to Namibia, a country they no longer knew. Indeed, many of them are still seeking a sense of home, culture, and identity after an upbringing that was marked by political fervor and instability.

D’EST. A Multi-Curatorial Online Platform for Video Art from the Former ‘East’ and ‘West’: “ReTopia”, Public Screening at Haus 22/Former Stasi Headquarters in collaboration with wild recuperations. material from below, video on screen: Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz, “Charming For The Revolution”, 2009. Photo by Emma Haugh.

Using an archival format, the D’EST program reflects a similar critique of dominant historiography to the one espoused by Wildes Wiederholen by refusing to accept a purely linear approach, and the geographical binary that would pit East against West. Rather, the platform seeks to represent queer and intersectional feminist approaches to post-socialism as moments of transformation taking place on a global scale. In both cases, a search for embodied and affective knowledge beyond the everyday discourse of post-socialism is paramount. By embedding this research and these works within the framework of the Archiv der DDR Opposition and the imposing architectural complex of the Stasi Museum and the Campus of Democracy, both Wildes Wiederholen’ and the D’EST ReTopia chapter 6 perform a critical gesture against the institutionalization of history by repositioning it as an ever-evolving work of art, and by exposing its inherent fictional qualities.