From Biopolitics to Necropolitics: Marina Gržinić in conversation with Maja and Reuben Fowkes

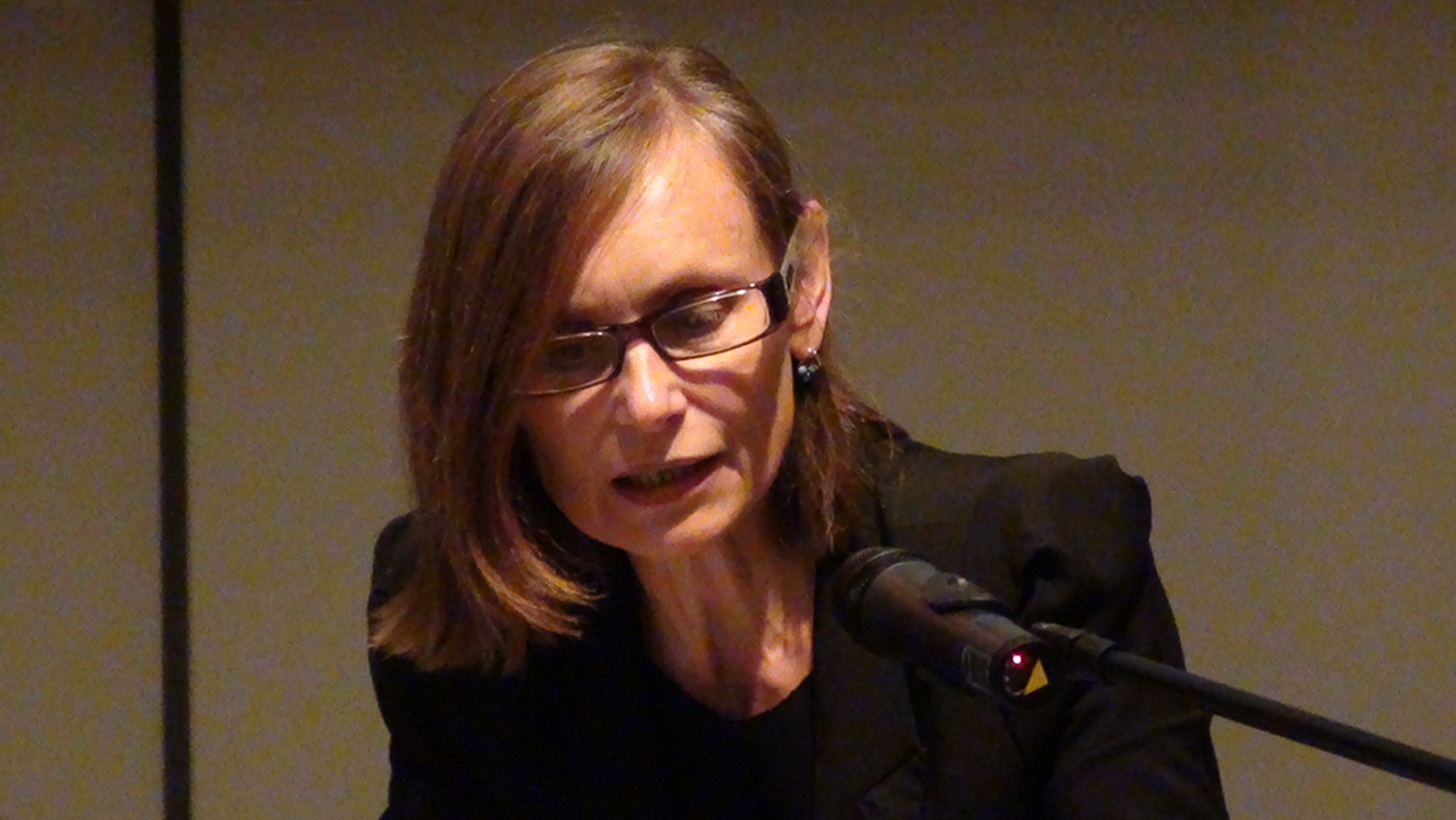

Marina Grzinic is a philosopher, artist and theoretician, and a research director at the Institute of Philosophy at the Scientific and Research Center of the Slovenian Academy of Science and Art in Ljubljana, Slovenia. She is also a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, Institute of Fine Arts, Conceptual Art, in Austria. Grzinic was in Budapest recently to give a lecture A Passion for History in the Depoliticized and Castrated European Union Regime, as part of the Ludwig Museum’s lecture series, Theoretical and Critical Problems of the Margins Today. Maja and Reuben Fowkes met with her to discuss her lecture and her provocative views on Europe, globalization, and the failings of the institutional art world.

Maja and Reuben Fowkes: In today’s globalized world can we still talk about the margins when discussing East European art?

Marina Grzinic: Yes, I think we can, although the margins are obfuscated; they exist differently than they did in the past. In my view, it’s important to think in terms of the analysis of global capitalism and contemporary art, and our duty as researchers and critics is to rethink a present mode of capitalist production in relationship to contemporary art. I call this a historicization of capitalism. What can we detect in the relationship between global capitalism and contemporary art? This relation conceals the difference between the center and the margin, making it almost impossible to take any kind of critical position, as everyone is implicated and/or entangled, and as a result the margins are produced as heterogeneity, as style. Where are the margins? The margins are in the system of production. For example, we are sitting on the terrace of this fancy café, but nearby people are living on the verge of poverty. So, in fact, the margin, in a situation of both homogeneity and heterogeneity, is to say “sitting” with us at our expensive table.

MRF: You have talked about Europe as a fortress of racism, anti-Semitism and anti-migrant laws, which seems almost ironic in a Hungarian context in which European Union laws are seen by many as a protection against local excesses.

MG: Racism has a particular history, just as capitalism does. If you talk about structural racism, then racism is a major logic in the representation and productive cycles of global capital; it’s about the processes of racializations and the division of labor. While racist measures are imposed, they are typically translated into a technical vocabulary. This is why to understand what is going on we should think of the passage from biopolitics (the regulation of life) to necropolitics (the regulation of death). This is the case today: an intensified managing of death for profit. Maybe we were misled in the 1990s; today, everything is entangled and the multiculturalism of the 1990s can be seen as the initial process of racialization, segregation and discrimination at the center of so-called global (without borders) capitalism.

Racist necropolitics is also present in the art and cultural spheres. It consists of a process of ethnic cleansing of histories and movements that were problematic in the past. In other words, today the history of art and culture is cleansed of foreigners and foreign elements for the need of the nation-state. It does not come as a surprise that this specific cleansing of history is very present in Slovenia, my country.

A curator from Vienna told me that she was listening to a public presentation of the history of Škuc Gallery from Ljubljana, Slovenia, in a seminar on curatorial practices in Vienna. The Škuc Gallery was a key institution in Ljubljana through the 1980s on for the then underground, and later for independent art and cultural movements. But the speaker from Ljubljana completely omitted names and positions that actually formed this history. As this is still known in the international framework (though the process of cleansing is continuous in Slovenia), the speaker from Ljubljana was asked what she was doing. She was so shocked that something like this could be even asked (in Ljubljana it is so normalized), that she could not even give a banal answer to such an important question.

This is what I call a process of racialization of a necropolitical type! It affects mainly those curators, activists and positions that are not in blood and soil pure Slovenian. It is terrible to see that such racism is practiced by the new generation of lecturers and supported by the old generation who want to rewrite history for their proper benefits. This type of blunt racism is also seen as an “effort” to build the Slovenian nation-state that is only twenty years old.

MRF: Does anything remain of the dream of Europe that flourished after the end of the Cold War?

MG: We can see that capitalism has two major drives: privatization and the maximization of profit. The story of the emancipation of capital is based on the idea of privatization at any cost, so that every square inch of space and every life are privatized; as a result, you are owned by a system of laws. My interest is in the move away from a process of belonging (in a Deleuzian sense); one aspect of this is the change from biopolitics to necropolitics. The biopolitical welfare state has now changed into the necropolitical as a result of discrimination, regulation, flexible labor and a parallel process of institutional normalization and control over which discourses have the right to be presented. We can also think in terms of the passage from the nation-state to the “war-state” that has as its outcome the decline of the dream that the nation-state can decide its own affairs. Today the only area in which the nation-state has the power to decide is within culture; all other issues from the economy to the legal system to international affairs are controlled by transnational capital.

MRF: Is there still space within the institutional structures of contemporary art, with its cycles of biennials and art fairs, for opposition to the capitalist system?

MG: I would suggest we think about two examples that prove that this space is limited: the Former West project and Documenta 13. Former West is, in fact, a well-funded cultural project; it is, as stated online, a contemporary art research, education, publishing and exhibition project that was initiated in 2008 and will conclude in 2014. Today almost everybody is involved in the Former West project, with money coming from the European Union. I see it as a very damaging project; in terms of production, it is responsible for the evacuation of the history of former Eastern Europe through a fictionalization of history. It makes fictional and performative certain historical divisions, since if we accept the idea of the “former West” then the implication is that we’re all in the same boat. We have a double passage, from an internal division of East Europe and West Europe to former East Europe and former West Europe, as the Westerners like to call themselves today. It is striking that in their usage of the term “former” it is not placed in quotation marks; instead, it’s presented as a positive given, while in practice the West is playing at being former. As in many EU funded projects, there’s a strong elite connected to money, and in order for such projects to be funded, they have to come close to the ideology of global capitalism and the EU. This project homogenizes the space of Europe; it evacuates the responsibility of the West in history: Western colonialism, power, capital and wealth. The new Europeans are cheerful, all embracing subjectivities that they enjoy a “Europe without borders,” the slogan that marked the fall of the Berlin Wall’s twentieth anniversary. Germany launched it as follows: “Come, come to the country without borders!”

Documenta 13 is also an interesting case, especially the paradoxical and obscure “retreat” organized for a small group of curators and theorists afterwards at the Banff Centre in Canada. Who can go for a retreat in the Rocky Mountains? Who can think in nature about what is going on in art and culture? It’s a really ideological goal. In terms of critical discourse, you cannot divide the retreat organized by those involved with Documenta 13 from the exhibition in Kassel; they are both ideological, but in different ways. They both play on the fictionalization of the ideological moment, not only in terms of content but also on the level of form. Today the art form is the most oppressive part of the art work/institutional framework, while the content is anyway seen as not important.

MRF: Could you comment on the legacy of conceptual art in former Eastern Europe, which has been a recurrent theme in the discussions at the Ludwig Museum, Budapest, events?

MG: I’m teaching at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna and when I got the job in 2003, I was asked to teach the class on conceptual art. It was not my invention; it was just given to me, but from my point of view it would be necessary to talk about de-conceptual art. Going back to the question of the division of form and content in art, what is bought for art collections in the West today is the rediscovered conceptual art from the East European context. But it is not a political context, but rather one that can be translated as an ethical demand against the totalitarianism of the East that was opposed to the democracy of the West (while Western Nazism and Fascism are forgotten). Why? Because this is what could not be accepted for the West: political conceptual art from Eastern Europe. Global capitalism functions with a precise depoliticization of every demand. The past and present generations of artists and artist groups from the former Eastern Europe are intensively controlled and are very selectively picked up. Mainly, their work has to show its fidelity to Western modernism.

MRF: What do you think about the recent revival of interest in IRWIN?

MG: The case of IRWIN is very complicated from my point of view. I grew up with IRWIN. While not part of the group, I wrote a lot about them, and think they need to be considered in this Neue Slovenische Kunst (NSK) context. It’s not just about IRWIN, it’s about the NSK project. The biggest influence is theexperimental musical group Laibach, which has an important place in the history of counter-cultural music in Slovenia. This last project in London is connected with this intensified process of depoliticization in order to be accepted in the art market. Now, the last opportunity an artist has to go abroad is to present oneself as some kind of paradoxical East European case, to swallow all your political standpoints, and hope you will be “bought” for a collection or something similar. It was noticeable that those who took part in the IRWIN conference were selected because they either live abroad or make their career abroad. They have to be very low key in terms of their political demands, have good affiliations with powerful institutional directors, not critique the Western system, be in an intimate relationship with those that regulate the market or have somebody take responsibility for who you are. Sexism is also working hands in the hands of the Western system, unless you are as completely transgressive as Slavoj Žižek and then you can stand as a guarantee for the others. And if an artist wants to be included in the system of the West, he or she has to have a Western curator or critic speak about his/her work, in a critique that made the artist’s career by highlighting an “odd” East European project and translating it into English or German, washing away some of the problematic parts then “selling” the whole project as the invention of the interpretative machine of the West. I think that IRWIN is paying a double price, as they also paid the price of a completely mute and blind art history from Slovenia and ex-Yugoslavia that completely neglected them and their importance; this art history was incapable of understanding anything outside of high modernist art. And we know that it is impossible to view modernism outside of colonialism, it is its other side.

The Hungarian version of this interview was published in M?ért?, the Hungarian monthly journal of contemporary art.

Maja and Reuben Fowkes are curators and art historians working from Budapest and London, whose work focuses on the theory and aesthetics of contemporary East European art.

Maja and Reuben Fowkes are curators and art historians working from Budapest and London, whose work focuses on the theory and aesthetics of contemporary East European art.