Yael Bartana Screening at Gene Siskel Film Center (SAIC)

Conversations at the Edge, Gene Siskel Film Center (SAIC), Chicago, March 4 – April 14, 2011.

Yael Bartana, known for her politically charged films and videos that explore Israeli culture and Jewish identity, will represent Poland at the 54th Biennale of Art in Venice, the first artist of non-Polish nationality to do so. Her project, and Europe will be stunned, co-curated by Sebastian Cichocki and Galit Eilat, “calls” for the return of Jews to Poland and the rebuilding of a multicultural society, as explored in her previous films Mary Koszmary/Nightmares (2007) and Mur I Wieza/Wall and Tower (2009). The third chapter of her Polish trilogy, entitled Zamach/Assassination (2011), will premiere in Venice, alongside the first two installments.

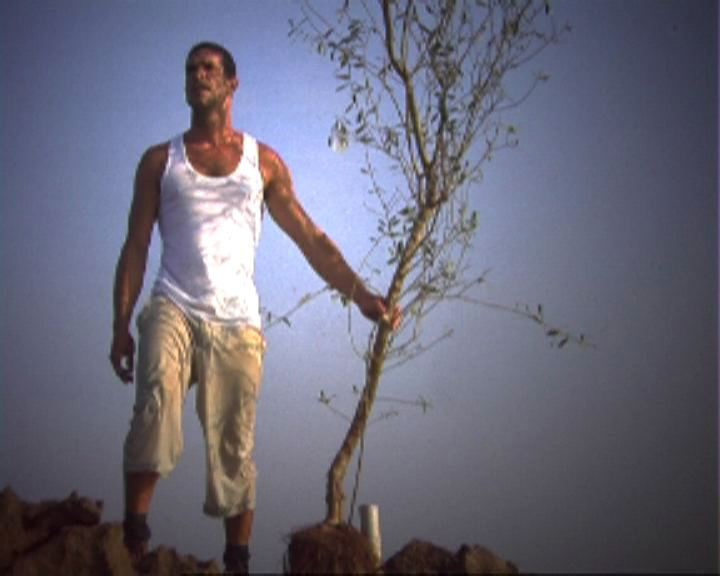

The artist recently screened seven works, including two of those to be exhibited in the Polish Pavilion, at the Gene Siskel Film Center of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where they were reformatted to be shown on a single screen. The series, entitled A Declaration, took its name from her 2006 work of the same title, in which a muscular young man in a rowboat lands at a rock in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea and replaces an Israeli flag that flies atop with a branch from an olive tree. This complex gesture of imperialism and peace contradicts the realities of continued territorial conflicts between Israel and Palestine, divesting such symbols of their true meaning.

The artist recently screened seven works, including two of those to be exhibited in the Polish Pavilion, at the Gene Siskel Film Center of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where they were reformatted to be shown on a single screen. The series, entitled A Declaration, took its name from her 2006 work of the same title, in which a muscular young man in a rowboat lands at a rock in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea and replaces an Israeli flag that flies atop with a branch from an olive tree. This complex gesture of imperialism and peace contradicts the realities of continued territorial conflicts between Israel and Palestine, divesting such symbols of their true meaning.

Issues of occupation and evacuation play out, literally, in Wild Seeds (2005), whereby a group of teenagers invents a game that simulates Israeli soldiers forcing Jewish settlers to leave their settlements. The camera centers on the aggressive action enacted by the young men and women who assume both roles. Subtitles translate the protestors’ words (“We shall conquer this land! Give up you fascists. Desert the army!”), at odds with the actors’ laughter and screams, connecting physical and political struggle.

Issues of occupation and evacuation play out, literally, in Wild Seeds (2005), whereby a group of teenagers invents a game that simulates Israeli soldiers forcing Jewish settlers to leave their settlements. The camera centers on the aggressive action enacted by the young men and women who assume both roles. Subtitles translate the protestors’ words (“We shall conquer this land! Give up you fascists. Desert the army!”), at odds with the actors’ laughter and screams, connecting physical and political struggle.

Bartana infuses all her works with similar tensions and contradictions, blending fact and fiction, past and present to question cultural definitions of nationhood and identity. These issues play out in an epic style (although the length of individual works range anywhere from six to fifteen minutes) that draws from traditional documentary, socialist-realist propaganda and the artist’s self-scripted narratives. The result is a unique, engaging aesthetic that, while distinctly her own, also pastiches the visual languages of her varied sources. Bartana ultimately creates her own iconic images to suggest parallels between political ideologies embedded within her historical materials and nationalistic forces in her native Israel.

One can place Bartana’s hybrid practice within a strain of contemporary art that Alfredo Cramerotti has termed “aesthetic journalism.” Artists using the tools and methodologies of investigative journalism, such as archival and field research, documentary and narrative storytelling, offer alternative views of reality, political and otherwise, than those presented by mainstream media. “Aesthetic journalism makes it possible to contribute to building (critical) knowledge with the mere use of a new aesthetic ‘regime,’ which has the effect of raising doubts about the truth value of the traditional regime.” (Alfredo Cramerotti, Aesthetic Journalism: How to Inform without Informing (Bristol, UK, and Chicago, IL: Intellect Books, 2009), p. 22.) “[T]his new mode of journalism [is] ‘aesthetic,’” writes Cramerotti. “[I]t happens when we take facts as artworks and artworks as aesthetic facts. [I]t questions, and levels out, our idea of representation as an artistic effort, and of engagement as a political one.” (Ibid., p. 109.)

For Summer Camp (2007), Bartana documented members of the Israeli Committee against House Demolitions (ICAHD) as they rebuild a Palestinian home destroyed in the occupied territories. Viewers witness Israelis, Palestinians and others working together in a spirit of purpose and unity, amidst the arid heat and ruins. The work takes its visual cues from Helmar Lerski’s Zionist-propaganda film Awodah (1935), which depicts the construction of settlements and the collective building of the new Jewish state. Bartana employs Awodah’s dramatic camerawork with its upward angles, focus on toiling bodies, hand labor and tools, and close-ups of individual faces. She also borrows its emotional, rhythmic soundtrack. In previous viewings, such as her first US survey at PS1 in New York (2008-09), the two films were shown together on opposite sides of a single suspended screen and synced to share the same score, as it seems they will be at the Biennale.

For Summer Camp (2007), Bartana documented members of the Israeli Committee against House Demolitions (ICAHD) as they rebuild a Palestinian home destroyed in the occupied territories. Viewers witness Israelis, Palestinians and others working together in a spirit of purpose and unity, amidst the arid heat and ruins. The work takes its visual cues from Helmar Lerski’s Zionist-propaganda film Awodah (1935), which depicts the construction of settlements and the collective building of the new Jewish state. Bartana employs Awodah’s dramatic camerawork with its upward angles, focus on toiling bodies, hand labor and tools, and close-ups of individual faces. She also borrows its emotional, rhythmic soundtrack. In previous viewings, such as her first US survey at PS1 in New York (2008-09), the two films were shown together on opposite sides of a single suspended screen and synced to share the same score, as it seems they will be at the Biennale.

Important to note is that Summer Camp was first shown in Chicago at the Spertus Museum, part of the Spertus Institute of Jewish Studies, in fall 2008, in the group show Imaginary Coordinates. The exhibition, which juxtaposed antique maps of the Holy Land with contemporary works about the same region by both Israeli and Palestinian artists, sparked debate when members of the museum’s board and private funders viewed it as “anti-Israeli.” The museum closed the show after a short run of only three weeks — a clear act of censorship. Bartana is not a stranger to controversy, however, as her works have also met with opposition in Israel.

While Summer Camp embodies the theme of construction/reconstruction as a critique of the ongoing demolition of Palestinian settlements and as an act of political defiance, the artist’s Polish trilogy explores notions of renewal/redemption amidst the history of anti-Semitism in Poland and Europe. Bartana is one of just a few contemporary artists dealing with the complexities of Polish-Jewish history and the traumas of Poland’s political past. That said, Polish artist Artur ?mijewski, with whom Bartana’s work shares affinities — namely the use of “archival construction,” both fictional and real, to lay bare mythic truths (Ibid., p. 74.) — has mined some of this same territory. ?mijewski’s Israeli Triptych (2003) is a series of films that addressthe lingering specter of the Holocaust on those living in Israel. In his 80064 (2004), ?mijewski persuades an elderly Holocaust survivor to allow him to retattoo his encampment number. Naked men and women play what seems to be an innocent game of tag in the earlier Berek/The Game of Tag (1999), until one discovers that the work was filmed in a former gas chamber.

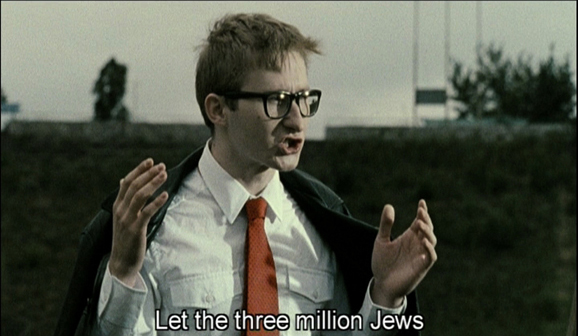

Parodying the aesthetic of nationalist propaganda films, Bartana’s Nightmares, the first work in the Polish series, is an open plea for 3,000,000 Jews to return to Poland to heal the wounds of the past and to build a future where Poles and Jews live as one. “Return today, and Poland will change, Europe will change, the world will change. And you will become different. Return not as shadows of the past but as hope for the future.” These words from a passionate speech orated in Polish by S?awomir Sierakowski, a prominent figure of Poland’s New Left, echo throughout an empty stadium, once the site of Communist political gatherings and rallies. Polish youth, dressed in what appear to be Young Pioneer uniforms, slowly assemble and write the phrase “3,000,000 Jews can change the life of 4,000,000 Poles” in white chalk on the stadium’s green field. At the end of the film, the youth, each holding a Polish flag, present Sierakowski with a bouquet of red flowers.

Parodying the aesthetic of nationalist propaganda films, Bartana’s Nightmares, the first work in the Polish series, is an open plea for 3,000,000 Jews to return to Poland to heal the wounds of the past and to build a future where Poles and Jews live as one. “Return today, and Poland will change, Europe will change, the world will change. And you will become different. Return not as shadows of the past but as hope for the future.” These words from a passionate speech orated in Polish by S?awomir Sierakowski, a prominent figure of Poland’s New Left, echo throughout an empty stadium, once the site of Communist political gatherings and rallies. Polish youth, dressed in what appear to be Young Pioneer uniforms, slowly assemble and write the phrase “3,000,000 Jews can change the life of 4,000,000 Poles” in white chalk on the stadium’s green field. At the end of the film, the youth, each holding a Polish flag, present Sierakowski with a bouquet of red flowers.

Fragments of Sierakowski’s speech form the subtitles for the subsequent Wall and Tower, in which a group of young Jews accept his invitation and return to Poland to build a kibbutz. Dressed as Jewish pioneers with their work shirts and khaki pants, they erect a new settlement in Warsaw’s Krasinski Square, site of the Monument of the Heroes of the Warsaw Uprising. Bartana uses an iconography similar to that of Summer Camp, along with echoes of Peter Weir’s film Witness (1985) and its romanticized scene of an Amish barn raising. When the barracks and walls are complete, a guard tower is lifted and on top is placed a flag that combines Poland’s coat of arms (a white eagle) and the Star of David. However, the work’s final scene, a bird-eye view of the finished kibbutz, suggests something less utopic, as it resembles a prison camp with its barbed wires.

Fragments of Sierakowski’s speech form the subtitles for the subsequent Wall and Tower, in which a group of young Jews accept his invitation and return to Poland to build a kibbutz. Dressed as Jewish pioneers with their work shirts and khaki pants, they erect a new settlement in Warsaw’s Krasinski Square, site of the Monument of the Heroes of the Warsaw Uprising. Bartana uses an iconography similar to that of Summer Camp, along with echoes of Peter Weir’s film Witness (1985) and its romanticized scene of an Amish barn raising. When the barracks and walls are complete, a guard tower is lifted and on top is placed a flag that combines Poland’s coat of arms (a white eagle) and the Star of David. However, the work’s final scene, a bird-eye view of the finished kibbutz, suggests something less utopic, as it resembles a prison camp with its barbed wires.

Here and throughout her work, Bartana explores the failure of the utopian project, whether socialist or Zionist, the kibbutz being an embodiment of both ideals. At the same time, she situates conflicts between Israel and Palestine, Jews and Poles, within a broader, if not Hegelian, context that calls for greater European and global responsibility for the plight of the refugee, much in the same way that Krzysztof Wodiczko has made visible the immigrant experience.

Here and throughout her work, Bartana explores the failure of the utopian project, whether socialist or Zionist, the kibbutz being an embodiment of both ideals. At the same time, she situates conflicts between Israel and Palestine, Jews and Poles, within a broader, if not Hegelian, context that calls for greater European and global responsibility for the plight of the refugee, much in the same way that Krzysztof Wodiczko has made visible the immigrant experience.

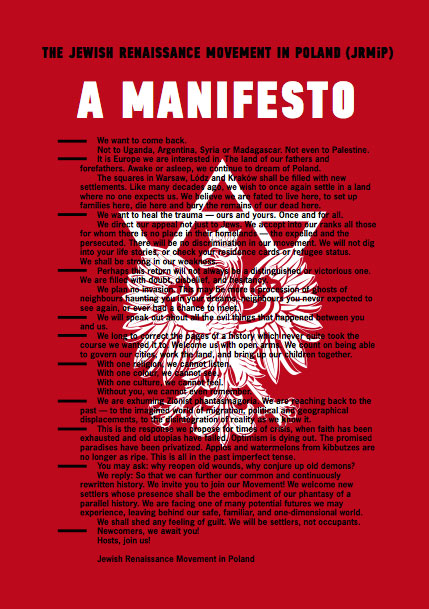

Yet despite the gravity of the issues she examines, the artist takes an ironical stance towards her sometimes controversial subject matter, as evident in her most recent project, The Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland. The movement’s manifesto co-opts Sierakowski’s declarations in Nightmares, and takes the form of mock speeches/performances and posters bearing the hybridized emblem from the flag in Wall and Tower. Through visuality, subjectivity, and a little absurdity, Bartana creates what Cramerotti calls “faction,” (fact + fiction), an artistic view of reality that might actually create the potential for change.