Performatism in Contemporary Photography: Alina Kisina (Series “New Critical Approaches”) (Article)

Most people in the art world by now have some sort of intuitive understanding that postmodernism is being replaced by something new, but few have tried to define what that “newness” is in a binding way. One of the few recent attempts of this kind was made by Nicolas Bourriaud while curating an exhibition called Altermodernism at the Tate Triennial in early 2009. Bourriaud suggests that the new post-postmodern art is the “positive experience of disorientation through an art-form exploring all dimensions of the present, tracing lines in all directions of time and space.” In his view, the artists involved in this turn into “cultural nomads” who “transport [signs and ideas] from one point to another” as a way of resisting the “economic standardization imposed by globalization.”

While there is no doubt some truth in this, Bourriaud remains vague about what makes a picture or installation specifically altermodern. And, many of his buzzwords—nomadism, plurality, as well as the notion of an “other modernism”—remind one strongly of the postmodern sensibility itself.(All quotes from Nicolas Bourriaud, Altermodern: Tate Triennial (London: Tate Publishing, 2009), no pagination.)

In articles in this journal and Anthropoetics, I have tried to take a more specific, hands-on approach to defining art in the epoch after postmodernism, or what I call performatism.(See in particular Raoul Eshelman, “Performatism, or What Comes After Postmodernism. New Architecture in Berlin,“ ARTMargins, 15 April 2002 <https://www.artmargins.com/index.php/archive/322-performatism-or-what-comes-after-postmodernism-new-architecture-in-berlin> as well as “Performatism in Art,” Anthropoetics 3 (2007/2008), <http://www.anthropoetics.ucla.edu/ap1303/1303eshelman.htm>.) While reasons of space prevent a full-scale exposition, it is possible to zero in on two sets of oppositions that can help distinguish performatism from postmodernism in photography. The first relates to the problem of order vs. disorder, the second to immanence vs. transcendence.

Postmodernist photography likes to decenter space and subvert central motifs. Space becomes an undecidable play of planes, forms, and positions that scramble conventional notions of up and down, in and out, surface and depth, center and periphery. The result is an undecidable ironic regress that forces us to accept the spatial coordinates of our world as contingent and constantly subject to change. We experience this regress spatially as a field of never-ending immanence, as an alternately playful and vexatious conundrum from which there is no escape. Postmodern photographers insert themselves into this shifting field of references without pretending to beautify or transcend it through art. Hence even carefully composed photos tend at first glance to look like accidental snapshots. And, such photos often deliberately focus on trivial or eccentric subject matter suggesting the random, off-kilter nature of the world itself.

Performatist photography, by contrast, works by artificially imposing authorial order on space (and, by extension, on the viewer) using a technique that I call double framing. Double framing means that the givens of the photograph work to create a “lock” or “fit” between a higher, invisible, unified authorial aim of some kind (the outer frame) and the individual spatial details of the picture (the inner frame). Basically, performatism is no less artificial and manipulative than is postmodernism. The difference is that instead of producing an endless regress of immanent references, the performatist photograph creates a binding feeling of unified order that seems to be directed at something above and beyond the immediate givens of the picture. These two sources of order—the authorial and the pictorial—are mutually confirming. On the one hand, the details of the photograph all seem to work together to point towards a higher, outside source of unity. On the other, when viewing the photo we realize that the source of that unity is nothing other than an author artificially imposing his or her will on the represented world and, by extension, on us. Whether we like it or not, we are drawn into the interior, orderly space composed by the author, even as we are aware that it is an artificial performance of his or her aesthetic power.

This authorial position of power also has direct implications for our attitude towards reality. As noted above, postmodern photography always “accidentally” reveals the world to be a kind of gigantic, vexing hall of mirrors with no higher goal, aim, or focal point and with no unified author behind or above it. Performatist photography, by contrast, “accidentally” always shows the world to be striving towards a higher order and unity. As the invisible higher source of that order, the photographer inevitably acquires a God-like or theist quality: he or she forces us to believe by using aesthetic means. This posture of belief is aesthetic, not institutional or mystical. It is the effect of a one-time performance and not a dogmatic, binding obligation or an attempt to experience nature or humanity as directly as possible. That is why performatism is not a warmed-over “other modernism.” It is neither a return to the surrealist quirkiness of Cartier-Bresson’s decisive moment, nor to the sensual, almost physically palpable still-lifes of an Edward Weston, nor to the all-inclusive humanism of Steichen’s Family of Man. Performatism is about an author forcing a particular illusion of order on a viewer and not about experiencing the material world directly or capturing it “as it is” in a particular, decisive instant.

I would now like to apply some of these insights to the work of a young Ukrainian photographer named Alina Kisina (b. 1983). Kisina, who moved to Edinburgh in 2003 and now lives and works in London, has made an unusual series of photographs of people and objects in Kiev and the Ukrainian province that deliberately avoids a documentary approach. Instead, Kisina has developed a half-abstract, half-representational photographic style that brings out the spirituality of the mundane objects and situations she photographs using dynamic formal means that are no longer compatible with postmodern irony. In doing so, she might indeed be said to create what Bourriaud calls an “archipelago” enabling “local opposition” to globalization.(“Altermodernism” (no pagination). Creating an oppositional space in regard to commercial culture is also Kisina’s avowed intent; in a BBC interview from 7 December 2008 she speaks of a desire to “turn inwards” as a “reaction against the shallowness of [Kiev’s] new commodity culture.”) I would like to go a step further than Bourriaud, though, and suggest that we can understand Kisina’s oppositional attitude best in terms of specific artistic techniques regarding order, space, and the representation of reality. These techniques differ sharply from those of postmodernism and provide the possibility of not just a local, but also a universal opposition to the commodity culture of globalization. In the following brief glosses of three of Kisina’s pictures I will show how this takes place.

Before turning to Kisina’s photos, it is helpful to take a quick look at how postmodernist technique works. Classic postmodern photography in America can be traced back to John Szarkowski’s path-breaking exhibition of the American photographers Lee Friedlander, Garry Winogrand, and Diane Arbus at MoMA in 1967. All these photographers could be contrasted in productive ways with Kisina. As a jumping-off point, however, I would like to use a picture by Lee Friedlander, whom MoMA curator Peter Galassi has aptly described as a “charlatan weaver of postmodernist webs” and whose use of reflection, frames, and the visual vernacular contrasts sharply with Kisina’s attempt to capture the interior space of her homeland on film.(Peter Galassi, Friedlander (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2005), 77.)

In Europe. 1973 Friedlander uses reflections in the storefront window of an anonymous European city to completely reorder our sense of order. Although the center of the photo is clearly marked by a thin white line on the left, by two white stripes on the right and by a box-like structure pointing diagonally towards the picture’s midst, the reflections in the window cause us to lose all sense of spatial orientation. Inside becomes outside (the woman appears to be sitting in the street), outside becomes in (the clouds are a photo in a travel agency rather than a reflection), up becomes down (the clouds are below and not above), surface becomes depth (the dark chair back to the right opens out into the street behind—or rather in front of—it), and space in general becomes entirely discontinuous (the multitude of competing frames creates an undecidable, confusing plurality of ordering quadrants). Not even the photographer himself escapes this irony; in the center foreground we can just barely make out two male torsos, one of which may well be the photographer—a quirky Friedlander trademark demonstrating that the photographer is pretty much on the same wavelength as his own weirdly scrambled subject matter.

In Europe. 1973 Friedlander uses reflections in the storefront window of an anonymous European city to completely reorder our sense of order. Although the center of the photo is clearly marked by a thin white line on the left, by two white stripes on the right and by a box-like structure pointing diagonally towards the picture’s midst, the reflections in the window cause us to lose all sense of spatial orientation. Inside becomes outside (the woman appears to be sitting in the street), outside becomes in (the clouds are a photo in a travel agency rather than a reflection), up becomes down (the clouds are below and not above), surface becomes depth (the dark chair back to the right opens out into the street behind—or rather in front of—it), and space in general becomes entirely discontinuous (the multitude of competing frames creates an undecidable, confusing plurality of ordering quadrants). Not even the photographer himself escapes this irony; in the center foreground we can just barely make out two male torsos, one of which may well be the photographer—a quirky Friedlander trademark demonstrating that the photographer is pretty much on the same wavelength as his own weirdly scrambled subject matter.

The photo itself parodies the notion of getting away or of transcending this kind of spatial confusion. Indeed, the nose of the airplane-on-a-stand is chopped off before it can even begin to take off into the photograph of clouds behind it. The photo is a brilliant theatrical demonstration that reverses the relations between center and periphery, depth and surface in a self-conscious, ironic, and mind-bendingly artificial way. Europe is unmasked as an illusion from which there would seem to be no escape. In fact, when you get right down to it, Europe is just a mirror image of the superficial, spatially jumbled America well known from Friedlander’s pictures of his native land.

Kisina’s photographs aim for effects that may be described without exaggeration as being entirely the opposite of Friedlander’s. Instead of an endless, ironic regress of immanent superficiality, her photos collected in the series The City of Home use reflection and a mixture of abstraction and representation to create an enigmatic depth and height suggesting a reality beyond that of the things actually depicted. Kisina, who is herself indeed a kind of nomad, had to return home to take these pictures. However, “home” refers not so much to a geographical space as to a spiritual one. As an example we can take The City of Home II, which at least superficially contains some of the same motifs as in Europe: multiple reflections interfere with our viewing a street scene containing a traffic light and vaguely European-looking buildings. This, however, is where the similarities end.

Kisina’s photographs aim for effects that may be described without exaggeration as being entirely the opposite of Friedlander’s. Instead of an endless, ironic regress of immanent superficiality, her photos collected in the series The City of Home use reflection and a mixture of abstraction and representation to create an enigmatic depth and height suggesting a reality beyond that of the things actually depicted. Kisina, who is herself indeed a kind of nomad, had to return home to take these pictures. However, “home” refers not so much to a geographical space as to a spiritual one. As an example we can take The City of Home II, which at least superficially contains some of the same motifs as in Europe: multiple reflections interfere with our viewing a street scene containing a traffic light and vaguely European-looking buildings. This, however, is where the similarities end.

Kisina’s photo appears to have been shot standing in front of a store window with a textured cloth behind it, so that the picture imposes three competing dimensions on us: the ornate floral pattern and folds of the cloth; the reflection of the street scene; and the conflation of the two dimensions in a third, enigmatically performative one that becomes the actual theme of the picture.

This can be seen more clearly when we view the picture from bottom to top. The bottom of the photo is dark around the edges in a classic, painterly sort of way; at the very bottom no reflection is evident and the space is two dimensional. As the eye travels higher up the picture we begin to see the three-dimensional folds of the patterned cloth and, through them, reflected striped lines that can be identified as a crosswalk leading into a three-dimensional, light-colored street scene. The folds of cloth seem to sweep upwards toward the reflected, lighter part of the picture and towards the traffic light, whose thick dark boom and thin cross-wires form a kind of cross; the horizontal wires mark the upper quarter of the picture (the sky) as a realm of its own. The light upper half of the photo, although now clearly identifiable as a reflected street scene, has the odd effect of turning the floral pattern underneath it into a positive image of the negative pattern beginning at the bottom.

The oddity of the picture doesn’t just have to do with two dimensions being superimposed on one another—anyone photographing a reflecting surface can achieve a similar effect. The strange thing is that both dimensions seem to act upon one another through mutually permeating materiality. Thus what begins as a two-dimensional surface opens out into two three-dimensional planes that are capped and united by a dynamic movement upwards. The picture opens out into a reflection of the sky (clouds are faintly visible at the upper right) and the boom of the traffic light projects upwards into that realm, drawing the eye with it. Markers of transcendence—the cross, the discrete section of sky, the upward movement—are held in check and slowed by the materiality of the cloth. However, they are nonetheless present and determine the ultimate dynamic and direction of the photograph—its performatist thrust towards something above and beyond the scene itself. The scene in itself is no less self-consciously artificial or illusory than Friedlander’s (this is why we’re not dealing with a return to modernism).

However, in this case illusion and artifice are put to use to convey a feeling of upwardly directed order—the transcendent performance at the core of performatism. This feeling of order creates a kind of enclosed, spiritualized space that is both local and universal at once: the semi-abstract cast of the photo allows us to participate in Kisina’s personal experience of her “city of home” without any specific documentary knowledge of what that home is. Kisina’s inner space opens out—at least potentially—into an outer space that would transcend the glitzy globalized culture that bounces around endlessly in Friedlander’s pictures.

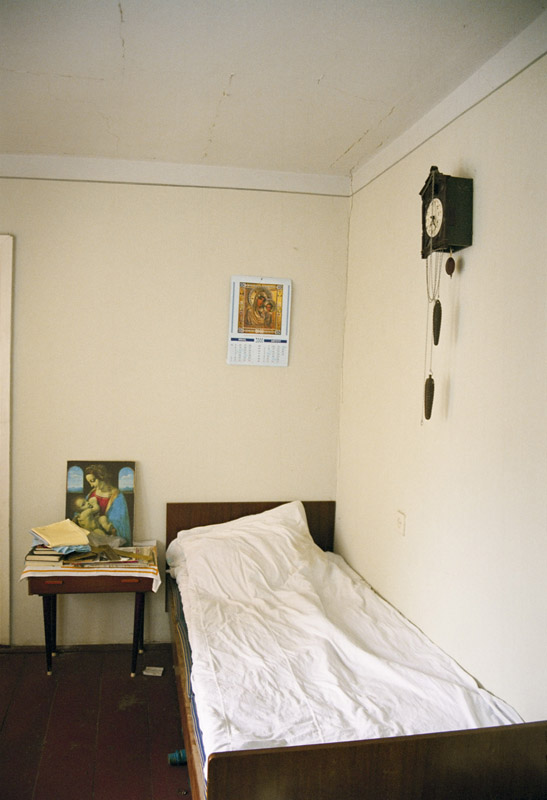

The next picture I would like to treat, Kolya and Others VI, seems at first more obvious in its spiritual intent. The picture shows a simple bedroom with a rumpled white bedspread whose form draws us forcefully into the picture’s lower midst and conveys a strong feeling of depth. The bed is flanked by a night-table on top of which rests a Renaissance print of a Madonna and child; above the bed hangs a calendar of an Orthodox icon (also with Madonna and child). To the right, hanging perpendicular to, and situated somewhat higher than the calendar, is a dark brown (cuckoo?) clock from which a pendulum and two oblong counterweights are suspended.

The next picture I would like to treat, Kolya and Others VI, seems at first more obvious in its spiritual intent. The picture shows a simple bedroom with a rumpled white bedspread whose form draws us forcefully into the picture’s lower midst and conveys a strong feeling of depth. The bed is flanked by a night-table on top of which rests a Renaissance print of a Madonna and child; above the bed hangs a calendar of an Orthodox icon (also with Madonna and child). To the right, hanging perpendicular to, and situated somewhat higher than the calendar, is a dark brown (cuckoo?) clock from which a pendulum and two oblong counterweights are suspended.

Before starting with any commentary on Kisina’s picture, it is instructive to take a quick look at a postmodern photograph from 1979 using almost exactly the same motif. Ruff’s picture, like most of his work at this time, is dedicated to rendering the space of petty-bourgeois interiors as banal, flat, and inert as possible (Ruff has famously stated that his photos capture “only the surface of things”).(“Inner Tension,” Tate Magazine, Issue 5, http://www.tate.org.uk/magazine/issue5/ruff.htm In spite of their seemingly offhand style, the pictures are carefully composed. Ruff used a large format camera (the negatives are 9 x 12 cm), a small aperture setting (f:45) and exposure times of up to two minutes. For more on this see Matthias Winzen, ed., Thomas Ruff – Fotografien 1979 bis heute (Köln: König, 2001), 177.) In Ruff’s picture, a kitschy Madonna with Child in a Black Forest setting hangs over two plumped-up feather beds and feather pillows on a double bed. Ruff effectively disrupts any positive feeling of depth, orderliness, and volume by cropping the feather beds both vertically and horizontally. The pristine orderliness of the plumped feather pillow in the lower center is repeated off to the right but abruptly cut off before it can achieve completion. The plain wooden headboard running off into hazy nothingness at a slightly downward angle from left to right suggests that this kind of banal orderliness could be continued on indefinitely. The painting itself, rather than imparting any sort of spirituality to the scene, is caught up in the spatial regress imposed on it by the off-center, low-lying camera position: foreshortening causes it to follow the horizontal movement of the headboard towards the white glare coming from the right of the picture. In a kind of ironic mis en abyme, the form of the pillow in the painting, on which the infant Jesus’ head rests, mimics the form of the pillows in the foreground, suggesting—take your pick—either the lack of a spiritual, caring presence in the bed, or a transfer of the bed’s formal banality to the picture. Whatever the case, the photographer has inserted himself into precisely that borderline position where we experience how the petit-bourgeois longing for order manages to stifle the petit-bourgeois longing for spirituality. Ultimately, though, the photo conveys a feeling that is less satirical than melancholy. The photographer seems able to capture this quandary on film but isn’t able to rise above or transcend it through his art.

Before starting with any commentary on Kisina’s picture, it is instructive to take a quick look at a postmodern photograph from 1979 using almost exactly the same motif. Ruff’s picture, like most of his work at this time, is dedicated to rendering the space of petty-bourgeois interiors as banal, flat, and inert as possible (Ruff has famously stated that his photos capture “only the surface of things”).(“Inner Tension,” Tate Magazine, Issue 5, http://www.tate.org.uk/magazine/issue5/ruff.htm In spite of their seemingly offhand style, the pictures are carefully composed. Ruff used a large format camera (the negatives are 9 x 12 cm), a small aperture setting (f:45) and exposure times of up to two minutes. For more on this see Matthias Winzen, ed., Thomas Ruff – Fotografien 1979 bis heute (Köln: König, 2001), 177.) In Ruff’s picture, a kitschy Madonna with Child in a Black Forest setting hangs over two plumped-up feather beds and feather pillows on a double bed. Ruff effectively disrupts any positive feeling of depth, orderliness, and volume by cropping the feather beds both vertically and horizontally. The pristine orderliness of the plumped feather pillow in the lower center is repeated off to the right but abruptly cut off before it can achieve completion. The plain wooden headboard running off into hazy nothingness at a slightly downward angle from left to right suggests that this kind of banal orderliness could be continued on indefinitely. The painting itself, rather than imparting any sort of spirituality to the scene, is caught up in the spatial regress imposed on it by the off-center, low-lying camera position: foreshortening causes it to follow the horizontal movement of the headboard towards the white glare coming from the right of the picture. In a kind of ironic mis en abyme, the form of the pillow in the painting, on which the infant Jesus’ head rests, mimics the form of the pillows in the foreground, suggesting—take your pick—either the lack of a spiritual, caring presence in the bed, or a transfer of the bed’s formal banality to the picture. Whatever the case, the photographer has inserted himself into precisely that borderline position where we experience how the petit-bourgeois longing for order manages to stifle the petit-bourgeois longing for spirituality. Ultimately, though, the photo conveys a feeling that is less satirical than melancholy. The photographer seems able to capture this quandary on film but isn’t able to rise above or transcend it through his art.

Kisina’s photo, by contrast, subtly and dynamically imposes markers of spatial transcendence on us. What is important is not so much the symbolic “message” of the two Madonnas with Child (which are no less kitschy than in Ruff’s picture), but their spatial position in a kind of upwardly striving, tripartite union with the clock (itself defined by the three-fold dynamic of the counterweights and pendulum). Having been thrust into the room’s inner space by the bed’s dark frame, our eye is forced upward towards the equally dark, three-dimensional volume of the clock, whose vertical dynamic now asserts itself over the horizontal one of the bed; the unmarked whiteness of the ceiling above it suggests a potential openness that contrasts starkly with the dark brown floor.

Unlike the inert, monotonous orderliness of Ruff’s bed, Kisina’s has an anthropomorphic twist to it. The slightly upturned pillow seems to be pointing toward the clock above, and the rumpled sheets bear a vibrant trace of that human disorder which Ruff deliberately expunged from his interior scene. The same goes for the objects lying on the floor, which suggest a disordered, though lived-in space. Whereas Ruff’s deliberately flaccid picture leaves us stuck in a spatial conundrum and holds forth only the promise of eternal return of the same, Kisina’s photo involves us in a strong narrative of spatial fulfillment. The pictures pulls us visually into a three-dimensional space in which all objects seem to be united in an upward, sublime thrust towards a ceiling that does not oppress or inhibit them.

This movement upwards is made even more dynamic because the opposing forms below seem to resist it. The Madonna at the bottom left faces to the left and the Madonna on the right faces towards the right; the upward twist of the pillow to the right is countered by the yellow stack of papers pointing towards the left; the objects on the floor reflect, respectively, the traditional symbolic blue of the Madonna’s cloak and the color of the sheets. Unlike Ruff’s picture, though, no ironic mis en abyme results. Any potential mirroring is resolved by the upward thrust of the objects taken together as a dynamic whole. The picture is locked in an evocative double frame composed of the details of the picture on the one hand and the invisible authorial will organizing them on the other.(Readers familiar with the theory of photography will notice the deliberate discrepancy between my account of performatist technique and Roland Barthes’ description of photography in Camera Lucida (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981) where he separates willed, intentional studium (roughly speaking: the picture’s theme) from the punctum (an accidental detail disturbing the studium but making the picture “prick” the viewer, as Barthes puts it). In Kisina’s work, the tendency towards abstraction and the painterly composition of the still-lifes create a unity that blurs any distinction between studium and punctum.)

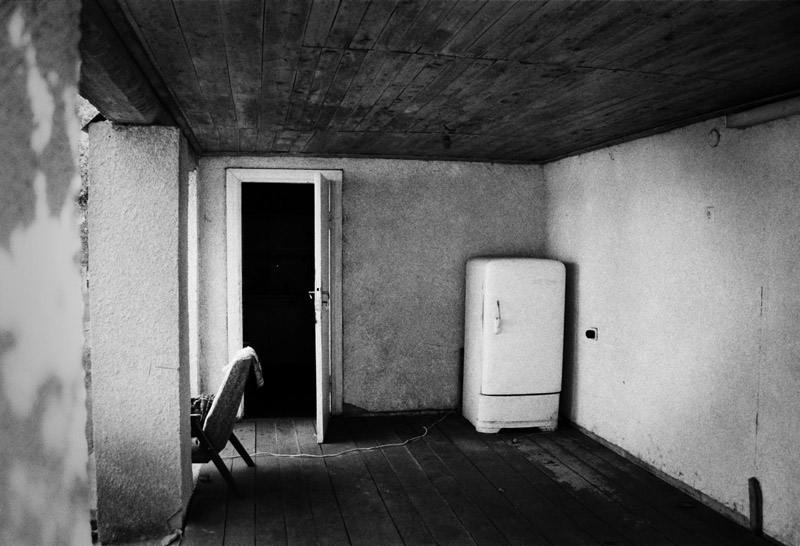

The third picture I would like to discuss is the absolutely extraordinary Kolya and Others IX, which presents a visual performance that is even stronger and more compelling than those of the bedroom scene or storefront window discussed above. The reason for this lies in the constricting, foreboding darkness of ceiling and floor, which effectively cuts off any chance of participation in the redemptive upward motion that informs Kisina’s previous two photographs. Yet instead of inducing a sense of postmodern claustrophobia in us, the picture projects buoyant, transcendent luminosity. Just how does this work?

The third picture I would like to discuss is the absolutely extraordinary Kolya and Others IX, which presents a visual performance that is even stronger and more compelling than those of the bedroom scene or storefront window discussed above. The reason for this lies in the constricting, foreboding darkness of ceiling and floor, which effectively cuts off any chance of participation in the redemptive upward motion that informs Kisina’s previous two photographs. Yet instead of inducing a sense of postmodern claustrophobia in us, the picture projects buoyant, transcendent luminosity. Just how does this work?

As in the bedroom scene, we are forcibly thrust into the room’s midst through foreshortening marked below by floorboards and above by the imprint of wooden molds on the concrete ceiling. The room, which at first glance appears to be closed, appears on closer examination to be an open, porch-like affair (we can see through the crack of some supporting pillars and a chair is positioned between one pillar and the back wall). The remarkable thing about the picture, of course, is the luminous volume of the refrigerator glowing softly in its solitary, closed-off corner. Its positive, radiant volume is made all the more powerful by being contrasted with the dark depths of the open closet set within its white frame. Indeed, the volume of the refrigerator thrusting out into the room seems to be the positive inverse of the infinitely receding emptiness of the closet.

Upon closer examination, all details in the picture seem to be aimed at and/or prefigure the refrigerator. The two columns on the left—the first blurred, the second sharp—in combination with the door frame anticipate the whole, rectangular volume of the refrigerator. The white electrical cord, the slanted, illuminated chair and the splash of light next to the fridge all force our attention upon it, as does the triangular relationship between the dark legs of the chair to the left, the vertical object in the lower foreground, and the dark switch or wall plug next to the refrigerator.

The picture, in short, enacts the metaphysical optimism that is at the core of performatism. The entire dynamic of the photograph corners us, leads us into a spatial dead end; but this end is filled out again with the radiant volume of a mundane material object that is able to catch and embody light from without. It is this paradoxical dynamic that makes Kisina’s work performatist. For the route leading towards transcendence (and out of the endless, ironic immanence of postmodernism) must pass through the weighty, massive hindrance of material form.

Kisina isn’t part of any scene or school and her career as a photographer is just beginning. However, her work may be viewed as a homespun, deliberately spiritual Slavic incarnation of the same performatist principle that informs the oeuvre of major contemporary photographers like Thomas Demand or Andreas Gursky. For Demand’s large-format pictures of archetypal cardboard models and Gursky’s digitally manipulated large-format compositions also create a double-framed lock between “accidentally” ordered pictorial details and the authorial will organizing them into a higher, inscrutable unity.(For more on this see Eshelman, “Performatism in Art” as well as Performatism, 206-216. Michael Fried has also noted the authorial and ontological innovations involved in Gursky’s and Demand’s work without however linking them up with a new epoch. Fried instead lumps them into his all-purpose category of “absorption” where they exist cheek by jowl with Ruff, Friedlander, Cindy Sherman, Thomas Struth, and a whole slew of other photographers who in my mind are eminently postmodern. For more on Gursky and Demand, see his Why Photography Matters in Art as Never Before (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), esp.. 156-182 and 261-277.) As of now it is premature to say whetherthe performatist aesthetic I have described above will leave the same imprint on art photography the way the work of Friedlander, Winogrand, Eggleston, or Arbus did 40 years ago. However, the will to order, unity, and interiority involved in it will no doubt exert a tremendous appeal on those who have grown tired of the postmodern house of mirrors with its focus on the deadening banality of the real and the eccentric destabilization of space and subjectivity. The most incredible information look here

Further reading in the “New Critical Approaches” series:

Tanja Ostoji?’s Aesthetics of Affect and PostIdentity (Article) by Bojana Videkanic

Andrey Kuzkin, Conceptualist Son (Article) by Yelena Kalinsky