The Shifty Art of András Gálik and Bálint Havas (Interview)

Introduction, by Edit András

The Hungarian artist duo Little Warsaw, a collaboration between Bálint Havas and András Gálik, started locally in the late nineties. Both had been trained as painters by established conceptualist artists who had been newly appointed to the academy. However, to these young students, conceptualism was an exhausted, outdated movement that they considered esoteric, aesthetic, and dry. They understood that conceptualism was accessible only to a closed, trained circle that was isolated even within the art scene. Havas and Gálik were equally determined in their refusal to connect with the newly established art market by means of the gallery system. Instead they articulated from the very beginning a critique of art as a way of making and distributing luxury consumer products.

In the turbulence of the early period of transition – Havas and Gálik began their studies immediately after the political changes – they faced the insignificance of culture as an active agent in the social sphere and the ineffectiveness of art’s rigid institutional structure, its inability to reflect the political and social changes. They felt a strong need to redefine art, extending it well beyond its traditional boundaries into the public realm. Their main intention was to communicate with an audience much wider than that of their narrow subculture.

After finishing the art academy, Havas and Gálik devoted themselves to the traditional medium of culture in an effort to cross the borders not just between two opposing fine art disciplines but also between mainstream and alternative art. Contrary to the generation before them they did not have a phobic relationship with the physical object. To them objects were something they could hold on to in the flood of virtual images that was having such a strong influence on the local scene. The most important thing, however, was the nature of the context in which the art object existed, with its complex social and psychological structure and invisible power-relations. The artists became interested in re-contextualizing and re-evaluating the media of classical art practice and in providing a subtle analysis of the art object’s context. To this end they developed strategies that helped them change that context through grafting and mixing while at the same time testing its flexibility and limitations. To Havas and Gálik the hub around which their practice evolved became the social sphere in which art operates.

After finishing the art academy, Havas and Gálik devoted themselves to the traditional medium of culture in an effort to cross the borders not just between two opposing fine art disciplines but also between mainstream and alternative art. Contrary to the generation before them they did not have a phobic relationship with the physical object. To them objects were something they could hold on to in the flood of virtual images that was having such a strong influence on the local scene. The most important thing, however, was the nature of the context in which the art object existed, with its complex social and psychological structure and invisible power-relations. The artists became interested in re-contextualizing and re-evaluating the media of classical art practice and in providing a subtle analysis of the art object’s context. To this end they developed strategies that helped them change that context through grafting and mixing while at the same time testing its flexibility and limitations. To Havas and Gálik the hub around which their practice evolved became the social sphere in which art operates.

Opposing the broad artistic migration toward the Western market in the 1990s as well as the aspiration of previous generations to achieve parity with current Western movements in the name of universalism, Havas and Gálik were eager to discover neighboring countries that had become totally out of fashion after the disintegration of the Socialist camp. In a time when solidarity between ex-fellow residents of the camp had evaporated amidst competition in courting the favor of the West, Havas and Gálik made the bold and often controversial decision to move further East.

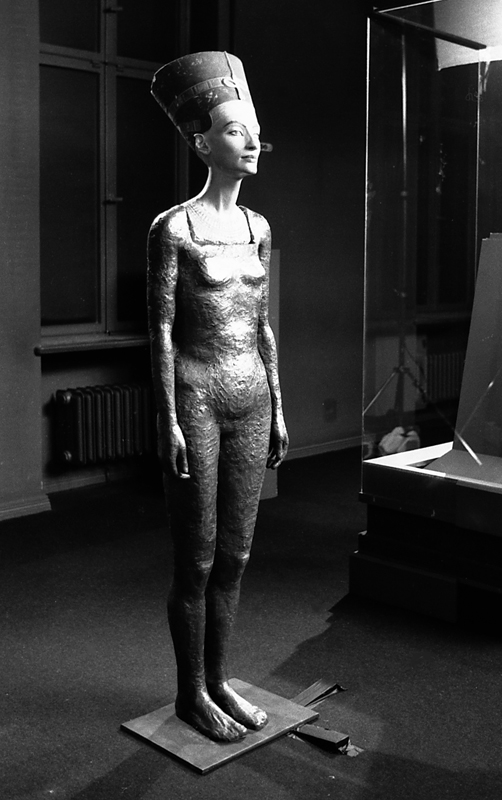

At the international level, their first conflict-provoking project was a project entitled The Body of Nefertiti. First displayed in 2003 in the Hungarian Pavilion of Venice Biennial, The Body of Nefertiti tracked the complex discursive exchanges among various members of the current art establishment, exposing the exclusionary and authoritarian nature of practices supposedly undertaken in the name of “pure” and “authentic” art. Havas and Gálik intended to add a cast body to the famous Nefertiti bust, which was taken to Berlin from Egypt in the beginning of 20th century, and exhibit the resulting sculpture in the Hungarian Pavilion of Venice. In fact, the body and bust were united cautiously in Berlin for a few moments, which were filmed, but the bust itself was not allowed to be carried to Venice. Thus, in the biennial one could see the body torso sculpted by Havas and Gálik but without the famous head—only a video-projection showing their brief joining in Berlin.

At the international level, their first conflict-provoking project was a project entitled The Body of Nefertiti. First displayed in 2003 in the Hungarian Pavilion of Venice Biennial, The Body of Nefertiti tracked the complex discursive exchanges among various members of the current art establishment, exposing the exclusionary and authoritarian nature of practices supposedly undertaken in the name of “pure” and “authentic” art. Havas and Gálik intended to add a cast body to the famous Nefertiti bust, which was taken to Berlin from Egypt in the beginning of 20th century, and exhibit the resulting sculpture in the Hungarian Pavilion of Venice. In fact, the body and bust were united cautiously in Berlin for a few moments, which were filmed, but the bust itself was not allowed to be carried to Venice. Thus, in the biennial one could see the body torso sculpted by Havas and Gálik but without the famous head—only a video-projection showing their brief joining in Berlin.

In The Body of Nefertiti Havas and Gálik chose their object of appropriation very carefully. They selected a short but very turbulent period of Egyptian history – the time when Akhnaton converted to monotheism – whose memory was subsequently erased by his successors. Contemporary Eastern Europe, as it turns out, has an intimate relationship with the vanishing and the rewriting of history.. In addition, the two male artists chose a powerful woman as the object of their appropriation, in so doing embedding in the piece a radical critique of the power relations that determine who is allowed to criticize the system and reuse others’ objects.

When The Body of Nefertiti was displayed, critics in the Egyptian press accused the artists of being disrespectful of old masters and sacred art, and even of humiliating Nefertiti with an inappropriate body. Rooted in Islam’s ban on nakedness, however, their main accusation was perhaps invalidated by the fact that the original sculpture was made long before the Arabic invasion of the ancient Egyptian empire. Thus, although the artists’ Islamic critics offered their criticism in the name of universal beauty and artistic values that had supposedly been tainted by Havas and Gálik’s intervention, their understanding of the treasured sculpture’s “original” condition in fact relied on the impact of postcolonial discourse. Although they tried to conceal the power relations implied in their attack against an advanced contemporary art project, in their eyes the crime became more serious given that it was committed by largely unknown artists. The relative anonymity of Havas and Gálik and the fact that they hide behind an enigmatic name (itself a challenge to the institution of authorship) helps explain the absence of any relevant media coverage for the project.

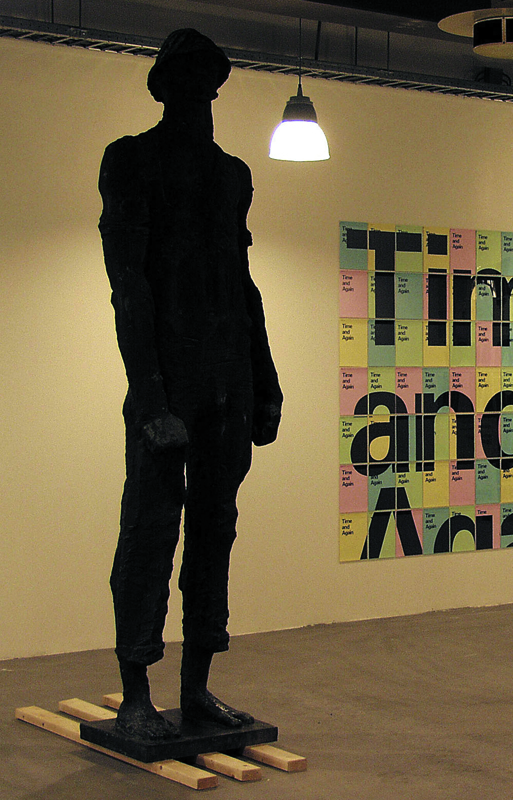

The other conceptually oriented project I intend to analyze in this piece was shown in Amsterdam at the exhibition Time and Again (2004). On this occasion, Havas and Gálik took a Hungarian public monument made in 1965, József Somogyi’s statue of János Szántó Kovács, from Hódmez?vásárhely, a southeastern Hungarian town, to the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. In this case, the target of their operation was the art making practice of their own recent past, located outside of the museum in the public space of Socialism. Time and Again asked how that practice, still a part of their visual environment in the form of statues and other public monuments, might function within the international space of the contemporary art world. This time, the dislocation wasn’t just virtual: the statue in its entirety was moved to the prestigious Amsterdam museum.

The temporary relocation of the monument raised a harsh debate in Hungary. Evoking the days of rebellion against official cultural policy, the Art Academy, the institute of leading artists established in the new era, published a petition and collected signatures against Havas and Gálik’s action. Leading representatives of both the cultural right wing and liberal left signed the petition side by side, in their objection finding a rare piece of common ground on which to stand. After the fall of the Iron Curtain, it became obvious that the seemingly homogenous countercultural bloc of Socialist times was in fact very diverse, so it split apart accordingly. That in reusing and re-contextualizing an art object from before the fall of the Iron Curtain, Havas and Gálik momentarily restored the illusion of political homogeneity on which the Socialist power structure so relied demands a more involved consideration of all the gesture.

In 1965, the fate of Socialist Realism was in question because its definition had started to become vague. 1965 was also the year of the original unveiling of the statue of János Szántó Kovács, who was the agrarian-proletarian leader in the early twentieth century. Thus, this very statue became a site of struggle, where competing positions regarding the balance between state control of art and the imperative of artistic freedom of expression were contested. The sculpture was accused of not being heroic enough by those who adhered to the standards of the official style, while others, especially those in the art community, celebrated it for its daring disregard of official style. Though it was not long before this explosive debate was forgotten, all these issues came back into play when Havas and Gálik re-unveiled the statue in 2004, and in the process debate was stirred anew. At home, Havas and Gálik was decried for not asking for permission from the Somogyi’s heir, and accused of humiliating the statue and, by extension, the artist himself. In spite of broad concordance on these matters, I would argue that as the statue was in no way harmed in its relocation and subsequent repatriation, Havas and Gálik’s Time Again only lifted the veil of ignorance off a statue whose daring and controversialhistory had been too long forgotten.. Like The Body of Nefertiti, Time Again questioned who has the right to dig up, in this case, Hungary’s own Socialist past, thus insisting upon an interrogation of both the interests implied in and the consequences implied by the accepted distribution of historical authority.

Havas and Gálik’s effort at dusting off the past in the case of a Socialist monument was not celebrated but, on the contrary, policed. However, this time the policing was done not by another country’s cultural leadership, and not by the state cultural bureaucracy, but by the art community itself. One can’t help but suspect, in light of this, that the real fear — the attacks on Time Again and by extension the real urgency of the intervention — was that the representatives of Hungary’s once rebellious avant-garde would be revealed as, within the conditions of the country’s changed sociopolitical situation, mere guardians of the established tradition, in this respect no different than the authorities against whom they had directed their celebration of Somogyi’s controversial statue just a generation earlier.

Interview with András Gálik and Bálint Havas (“Little Warsaw”)

Sven Spieker: One of the things critics most often seem to want to discuss when it comes to your work is the issue of conceptualism, the once-dominant (and then once again dominant) type of art production in the so-called New Europe. I want to bypass this question for now and ask you about your attitude towards art movements in general. One can divide artists into two groups: those who believe that you need to “run through” all existing movements before you can reach your own (Malevich, Duchamp), and those (a much larger group) who begin as if nothing had preceded them. Which side are you on? Do you think it is necessary to be a conceptualist before you can become (for want of a better term) a “neo-conceptualist”?

Little Warsaw: Actually, we do not know if we are neo-conceptualist artists or not. During our studies, it was minimalism and different reductive forms of expression that were interesting for both of us. When we began working together, it was a revelation for us to learn about and get familiar with the work of the Situationist International, and this has become one of our corner stones. We paid more and more attention to the social context of our work. The paradigms that characterize our activity gradually took on definitive shape. We considered our works complex projects. After a while, we got into public research activity, which took us further into issues of performativity in art. One of the most important factors proved to be the social context: how does it work, what is its origin? Actually, this was the point where the individual achievements of conceptual artists became really substantial for us and our work.

S.S.: Some of your best-known work takes on sculpture. I am thinking of Flag (2002); your creation of a new bronze body for the Nefertiti bust kept at the Museum of Egyptology in Berlin (The Body of Nefertiti, 2003) at the Venice Biennale (2003); or the transfer of József Somogyi’s statue of János Szántó Kovács from Hódmez?vásárhely to Amsterdam’s Stedelijk museum (Monument contra Cathedral – Instauration, 2004). People have argued over whether or not these works represent instances of (conceptual) reduction and dematerialization, or not. Of course, there is something here of the kind of context-switching that became a staple of idea-driven, institution-critiquing art after Duchamp. Funnily enough, though, as I was thinking about these projects I became more and more convinced that the key to them is not the completed switch from one context to another but what happens in between. We might call it “transit”: you act like a person who sendsthings by mail from East to West, and back. And like every mail customer you have to reckon with the possibility that upon delivery your work will not be treated the way it should be treated. In the case of the János Kovács Szántó sculpture, the museum workers in Amsterdam horribly mislabeled the sculpture once it had set its feet on the Stedelijk’s floor, while back in Hungary everybody was up in arms about the transfer. Or, in the case of Deserted Memorial (2004)—which involved the transfer, or transit, of a defaced commemorative plaque from Budapest to The Hague—the plaque arrived in Holland completely blank, with no message whatsoever on it… Can we think of your work as an instance of mail art?

L.W.: You are right, the most interesting thing for us is how a given object gets from A to B. The operation itself is important for us. We move objects that for all kinds of reasons are hard to move and it is very important that we move the original object and that we move it in an actual, material, physical sense. Mail art uses an existing infrastructure, and mail artists generate movements within that existing structure. We are not using an existing structure. We use an object, which, if we are to move it or to make it an object of any operation, we need to do something with the specific infrastructures that it belongs to, and this “something” is always different for each new work. It differed greatly in the case of the Nefertiti head and in the one of the János Szántó Kovács sculpture. We need to set up a connection with these infrastructures to change the process that leads the object from A to B. We want to see how we can influence this process, and how our connection, in return, influences this process in a dialectical way.

S.S.: Edit András has remarked—correctly, as far as I can see—that you have replaced the East/West perspective that was typical of the previous generation of artists (who matured under Socialism) with a kind of East/East viewpoint that looks more to your Eastern “backyard” than to the West. What’s attractive to you about that yard?

L.W.: Rather than being in some sense exotic our work is strongly connected to the local context. We use elements that are not only and simply the results of a general sort of sociological survey or research but that come from a deeper and more complex set of pieces of information. We use information that can only be gained in the local context. This information cannot be viewed from a global point of view or treated with a global attitude. The data we use are informal; they may come from local urban legends and are rooted in the local social space and in how we have been socialized locally. Legends, social space, locality – these are the most important elements for us. We have also tried to formalize the way we receive these data; however, it has always been very difficult to formalize these situation- and context-specific contents. Our work is not really comparable to sociological research; it is more like a probing anthropological investigation. We do not set up a questionnaire or a data base – instead we work as participants.

What is attractive to us about this “local backyard” is that there is some kind of self-knowledge that we can gain from it. To be honest, this backyard is not always attractive at all, quite on the contrary, it is often unpleasant and full of conflict. But there is the promise of self-recognition in it, and it is attractive to analyze this situation, our context and the place where we come from and that formed us. This analysis is a positive process; it is a positive thing to analyze this thing we are in. But this positive approach is more of a hypothesis. The outcome is a lot more disappointing.

S.S.: Would you agree that the “dialectical” tug-of-war that characterized—not only in Hungary—oppositional (conceptual) art under socialism, and which was followed in the 1990s by the monumentalization of that war (and by the forgetting of socialism) has now entered the period of self-questioning?

L.W.: Yes, we agree, now it is the time of self-reflection. We understand this self-reflection and self-questioning in reference to the role of the artist in the present situation. We belong to a younger generation, but we have often seen that artists who lived and worked in the previous (Communist) era tend to mythologize their own activity. They were illegal in the former era and opposed the prevailing power system and social structure. There is a difference in how we perceive and interpret their activity and their point of view. We seek to de-mythologize and de-sacralize them, in other words, approach them in a more matter-of-fact way. They see their own activity in a heroic light and dramatize themselves through a sort of political mythology, against a political backdrop.

S.S.: Tell me something about your studio-cum-gallery in Budapest. What’s your attitude towards commodification and the art market? As you know, Duchamp could do both: sell art (that of others, mostly), and be quite indifferent (even disdainful) to the idea of art as commodity. Where do you come down on this issue?

L.W.: We do not believe in the category of the art object as a consumer item. All of our works are complex contextual works, social plastics, not commodified art objects. The point is that our projects are not motivated by the market. We do not want to conduct a studio practice to produce for a gallery, or to sell our objects in the art market. Our intention is not to be marketable, but if it comes to that we will not protest against it either. We do not believe in this dichotomy, and accordingly we do not believe that this is a contradiction. We should add that the market can be an important field of artistic practice and intervention.

The market itself is flexible and follows what is going on. It cannot do anything else; it has to follow what is happening in art. We immerse ourselves in a project for a long time – often for months – and in the course of this long process we do not produce spectacular objects but we conduct research. The social dimension behind the project is really important, it is a complex activity. But there are market-oriented institutions that are interested in this type of activity as well.

Marcel Duchamp and other great heroic figures who took a strong position against the commodified art object, within 80, or 50, or even 20 years, have come to represent the biggest value in the market. Take Gordon Matta-Clark’s collages, for example. And since this is a historical development, contemporary galleries have an interest in such phenomena. Galleries try to adjust. The art work itself may resist the market; often it is hard to transform it into something marketable, and sometimes the work itself deals exactly with this resistance. We have never considered ourselves as fitting easily into this system, on the contrary, our works resist fitting in.

S.S.: One can get the impression that the medium of your artistic work is in fact the public, and that what you are doing is to carry out an analytical process that provokes your audience to react in some way, and in public. Very much unlike the conceptualists who communicated with their audience in an often cryptic code that remained inaccessible to outsiders, your premise seems to be thoroughly democratic: everyone has something to say… Is this a fair characterization?

L.W.: Yes, we can accept that. We are working in a concentric structure, in many layers. There are layers that are written in cryptic code and there are basic ones. The Nefertiti project, for example, can be both understood on a broad and democratic level and on a more elitist level that is only perceptible to a more engaged spectator.

S.S.: One of the quintessential, most emblematic modernist scenes is the beginning of Sergei Eisenstein’s film October, the destruction of the massive monument to the tsar “by itself,” by means of filmic montage. To Eisenstein, montage is capable of showing how destruction is the (dialectical) prerequisite for the construction of something new. Now, when you carefully transfer a sculpture from Budapest to Amsterdam in a way that avoids any impression of iconoclasm or violence against the monument, or when you propose to graft a new body on to Nefertiti’s severed head (interestingly, this became visible to most people through film only!), you seem to negate the dialectical link between destruction and construction that is so important to early 20th-century modernism. Instead you concentrate on art’s power to heal: sculptures find their way into museums; heads are restored to missing torsos, etc. At the same time, such “healing” always suffers from a basic deficiency: it can never be carried out in the place where the monument belongs. Healing, you suggest, never completely coincides with its object and its environment…. http://spravkavspb.cc/

L.W.: What is important is that we are not negating anything. We try to think broader, to carry this montage further. We really try to think through and push further this idea of destruction or iconoclasm as artistic method and as a meaning-producing gesture. Destruction is not simply a negation on our part; we do not simply negate according to a certain dialectics. We rather try to re-interpret and rethink these issues in new contexts or sets of contexts. We want to re-consider the fact that what we are dealing with is simultaneously a sculpture, a plastic object, a memorial, a public sculpture, and a social plastic.

We agree with what you say about healing. However, right from the beginning this healing is predestined to fail. So eventually iconoclasm is there as well but we do not actively promote it, nor does it begin with us. In the course of our operation we confront the object with a situation and it is this situation that puts the object at the mercy of iconoclasm, while we are practicing a kind of healing. Metaphorically speaking we bring the object to the hospital but there they amputate its legs and leave them in front of the hospital entrance. There is a tragic element in this process; our intentions are so idealistic that they are bound to fail. So for us the process destruction-construction that you mention in your question is actually reversed.

We would like to come back to your term “transit.” This kind of tragic element, this ominous shadow implies that there is no complete permeability ortransition between these contexts, no matter how hard we try to carry out this operation. So, there is no complete resolution of our projects, and what remains is tension. This emotional tension which is the result of the impossibility of a full transition also explains the indignation and controversy that often surround our projects. And here we can also take up what you said about democracy in one of your earlier questions. If this tension exists on an emotional level then it has to be democratic. As you said, “everyone has something to say.”

S.S.: One of the most persistent misunderstandings regarding your work seems to me to be the idea that you practice Verfremdung, the Brechtian procedure of constant de-sublimation aimed at establishing critical distance from any fictional frame. I think, on the contrary, that the innovative thrust of your removal of monuments from their place does not lie in an effort to direct desire at what is absent (Brecht’s negative aesthetic: the most important thing is always hidden from view and needs to be made visible by “making it strange”). The reason is that unlike Brecht, you seem not to be afraid of fiction…

L.W.: You are absolutely right, fiction is very important to us and our work definitely has a fictional element. When we developed the Nefertiti project there were several moments that could have resulted in an even higher degree of “making it strange (Verfremdung). Naturally there was distancing involved – after all, this was not a Hollywood movie – but the fiction was never eliminated or deconstructed. There is a childlike fictional element in this project that offers the opportunity for empathy. Empathy is an important to us and we definitely use it. We cannot sharply distinguish between these elements – both fiction and absence (of Nefertiti’s head) are important constituents of our work.

S.S.: Do you consider repetition a crucial procedure for your work? I am thinking not only of your retooling of existing monuments in the works mentioned above but also of works such as Reconstruction—Isolation Exercise—Cyrill & Method where you asked Tamás St. Auby to repeat a performance from 1972. Repetition has a long pedigree in postwar art, and the meaning of this concept goes well beyond its postmodern banalization as quotation or pastiche. In the context of South-Eastern Europe, what comes to mind of course is NSK, Laibach, Goran Djordjevich, etc.—the idea of using copying as a form of critique. Do you see any links to your work?

L.W.: As opposed to and beyond the examples you mentioned, our criticism is not a direct and sharp social criticism. For NSK, repetition and recycling are based on contemporary social philosophy and come from postmodern ideas. NSK reflects and criticizes issues such as the fact that brands dominate all walks of society, etc. We are more into analysis, our works represent a more specific, more concrete form of criticism and we place them in certain specific contexts. We do not have a general critical attitude that could tell people just how awful our society is. We pick up one specific case and we work within that narrow field and context, though of course we use this context in a critical way. When we picked up the statue of János Szántó Kovács or ask Szentjóby[Tamás St.Auby] to repeat an existing performance that repetition implied a critical attitude, but in a very specific way. We like to stick to a narrow field. In an aesthetic sense repetition in our work is completely different from NSK’s. In our work the outcome is more poetic. We allow our projects to be conceived as fiction. NSK’s projects are more direct and should be understood on a subversive level. If their projects were viewed as fiction they would appear as something completely different.

S.S.: Could you comment a bit on your recent contribution to Manifesta 7, the video installation The Ship of Fools? I did not have a chance to see the project but it seems to me that it raises interesting questions about the nature of the site-specificity of facts…

L.W.: You are right, facts are site-specific and this is something unexpected and surprising to us. One would imagine that facts were the same everywhere. In our earlier works we moved an object with all its intellectual and emotional baggage and placed the whole package in another place and context. This is what earlier on you called transit. Our work for Manifesta 7 was an attempt to take this a step further by repeating an entire situation in this way. It was an experiment to repeat a situation in a reconstructed context.

June 27, 2009

Translated by Hedvig Turai