“Vuk Ćosić: Out Of Character” at Threshold artspace, Perth (Exhib. Review)

Vuk ?osi?: Out Of Character, Threshold artspace, Perth, Scotland. August 1 – November 1, 2009

Perth is a word derived from Old Norse, and is one of the ancient rune symbols, denoting mystery, games of chance, and gambling. Perhaps it was a mix of coincidences that led the Threshold art space to be headed by Sofia-born curator Iliyana Nedkova. After all, what are the chances of a curator from the central Balkans landing in the middle of Scotland? This unusual combination must have appealed to Vuk ?osi?’s sense of play when he agreed to his first-ever solo exhibition in Scotland to be hosted in Perth.

Essentially a mini-retrospective covering elements of ?osi?’s artistic practice from the late 1990s onwards, the show is not a conventional gallery presentation, and in keeping with Threshold’s program it is more concerned with presenting works in the public space. This approach seems to fit with the artist’s self-expressed desire to bypass the gallery system in order to directly address the public, an attitude echoed by his contemporaries within the net.art movement of the 1990s such as Heath Bunting, Alexei Shulgin and Olia Lialina.(See the artist’s statement to this effect in Mijuk Goran, “The Internet as Art,” The Wall Street Journal, 29 July 2009, Life & Style section, European edition.) ?osi?’s previous major outings in the UK (Liverpool in 2000, Gateshead in 2001) were both large-scale outdoor projections.(?osi?’s ASCII Architecture projected ASCII converted data over the ornate façade of St. Georges Hall, Liverpool as part of the festival “Video Positive 2000: The Other Side Of Zero”; See documentation of this event at http://www.ljudmila.org/~vuk/ascii/architecture/)

Upon entering the Threshold artspace, one is immediately confronted with an array of twenty two LCD screens mounted under the sweeping copper clad ceiling: The Threshold Wave, a permanent 22-channel video installation the content of which varies according to each exhibition in which it is shown. For Out Of Character, the screens display scenes from twenty classic films from the canon of cinema history, all rendered into glowing, green-on-black ASCII code.(ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange) is a digital communications standard introduced in 1963. “ASCII is not art. It’s a code, a way of hiding things within a smaller thing.” Tom Jennings, “An annotated history of some character codes or ASCII: American Standard Code for Information Infiltration,” 1999-2004, available at http://wps.com/projects/codes/index.html) Those familiar with ?osi?’s work will recognize his signature technique, a form of pixellation of the moving images that makes it easy to read the photography-derived form of the images from a distance. When viewed closer to the screen, the image is revealed to be an abstract field of alphanumeric signs that constantly shift and change as each frame is played back. The overall effect is strange as the ASCII aesthetic hearkens back to an early age of computing when the user interface was text-based, rather than the graphical user interfaces we know today from the Apple Macintosh or Microsoft Windows.

Upon entering the Threshold artspace, one is immediately confronted with an array of twenty two LCD screens mounted under the sweeping copper clad ceiling: The Threshold Wave, a permanent 22-channel video installation the content of which varies according to each exhibition in which it is shown. For Out Of Character, the screens display scenes from twenty classic films from the canon of cinema history, all rendered into glowing, green-on-black ASCII code.(ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange) is a digital communications standard introduced in 1963. “ASCII is not art. It’s a code, a way of hiding things within a smaller thing.” Tom Jennings, “An annotated history of some character codes or ASCII: American Standard Code for Information Infiltration,” 1999-2004, available at http://wps.com/projects/codes/index.html) Those familiar with ?osi?’s work will recognize his signature technique, a form of pixellation of the moving images that makes it easy to read the photography-derived form of the images from a distance. When viewed closer to the screen, the image is revealed to be an abstract field of alphanumeric signs that constantly shift and change as each frame is played back. The overall effect is strange as the ASCII aesthetic hearkens back to an early age of computing when the user interface was text-based, rather than the graphical user interfaces we know today from the Apple Macintosh or Microsoft Windows.

?osi?’s fascination with ASCII is partly a result of his immersion in popular computer subcultures (BBS’s, ASCII art, computer games, hacking, cryptography), but his ASCII Cinema project also plays out the process by which digital computers have already transformed images: code and image are visible at the same time.(“Cinema as a Code,” in Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media, (Cambridge, Mass.; London : MIT Press, 2001), 330-333.) The artist is translating media, re-encoding, re-configuring images as text, data. The ASCII becomes a kind of moving hieroglyph, inscribing this transition, and creating a tension between two screen cultures: that of the moving image (film, television, and video) and that of computers.

Part of the presentation in Perth is an ASCII version of the Lumière brothers’ famous film of workers leaving afactory gate (1895), which arguably represented the beginning of documentary film. This is looped alongside scenes from other notable pieces of cinema such as King Kong (1933); Triumph of the Will (1934); Casablanca (1942); Singin’ in the Rain (1952); Ben-Hur (1959); 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968); Taxi Driver (1976); and The Matrix (1999). The kaleidoscopic juxtaposition of instantly recognizable imagery, combined with an arcane retro-futurist look creates a brooding presence. Seeing these iconic films en masse in such a way brings home the importance of history to ?osi?’s practice: one can feel the weight of the past hanging over his art, impossible to escape regardless of the up-to-date technology used to display the work.

A central pre-occupation is the foregrounding of his awareness of technological obsolescence and its effect on the meaning of cultural artifacts. In ?osi?’s works the (im) possibility of reading arcane computer formats becomes a challenge akin to deciphering ancient manuscripts. One cannot help but assume that this aspect of his artistic sensibility owes much to his formal training as an archaeologist.

The Balkan peninsula employs three different alphabets operating in close geographical proximity: Cyrillic, Greek and Latin. Growing up in Yugoslavia, with two alphabets used side by side, presumably enhanced ?osi?’s awareness of how meanings and language are codified. His family apparently had connections to poets who constituted the Serbian branch of the Surrealist movement during Yugoslavia’s inter-war period.(Author’s conversation with the artist, Edinburgh, 3 August 2009.) Indeed, the artist acknowledges that he takes cues from poetry and literature, both from Dada and Surrealism and the French Oulipo group.(Vuk ?osi?, 3D ASCII, An Autobiography, (Ljubliana: Ljudmila, 1999), http://www.ljudmila.org/~vuk/ascii/vuk_eng.htm) One can see similar concerns around letters and characters as form, and signifiers, rather than simply their conventional symbolic function of representing certain sounds.

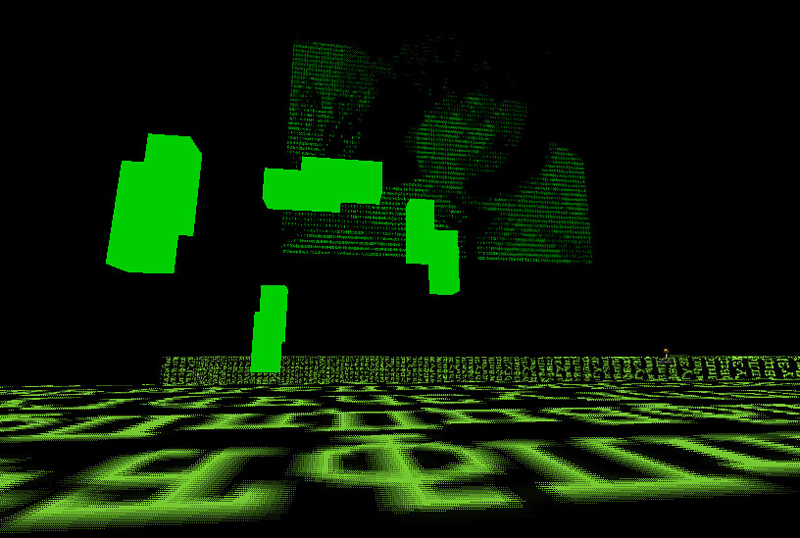

In ASCII Unreal (1999-2009), ?osi? fuses his obsession with ASCII characters with an interest in computer games. In this case, the chosen vehicle for his exploration is a specially modified version of the popular “first-person shooter” game “Unreal Tournament.” ASCII Unreal cleverly subverts the conventions of games that use realistic three-dimensional graphics, which attempt to immerse the player in a hyper-real Cartesian space, akin to the viewpoint of the camera in cinema. The artist replaces the virtual scenery with surfaces and shapes comprised of alphanumeric characters. Unlike his other ASCII projects, this work uses a code based on the Cyrillic alphabet.(For a detailed history of Cyrillic codes for computers, see Roman Czyborra, “The Cyrillic Charset Soup,” 1998, http://czyborra.com/charsets/cyrillic.html) This decision transforms the “Western” space of a perspective-based representation of reality – whose principles go back to at least the Renaissance – into an “Eastern” Slavic linguistic space that uses an alphabet whose origins go back to the medieval period in the Balkans, ?osi?’s birthplace. According to the artist, “the piece is dedicated to Mr. Danilo Ž. Markovic, the former Serbian minister of culture who once declared that ‘we all know that Cyrillic is not only the most beautiful script but also most suitable for work with computers.'”(?osi?, 3D ASCII, An Autobiography.)

In ASCII Unreal (1999-2009), ?osi? fuses his obsession with ASCII characters with an interest in computer games. In this case, the chosen vehicle for his exploration is a specially modified version of the popular “first-person shooter” game “Unreal Tournament.” ASCII Unreal cleverly subverts the conventions of games that use realistic three-dimensional graphics, which attempt to immerse the player in a hyper-real Cartesian space, akin to the viewpoint of the camera in cinema. The artist replaces the virtual scenery with surfaces and shapes comprised of alphanumeric characters. Unlike his other ASCII projects, this work uses a code based on the Cyrillic alphabet.(For a detailed history of Cyrillic codes for computers, see Roman Czyborra, “The Cyrillic Charset Soup,” 1998, http://czyborra.com/charsets/cyrillic.html) This decision transforms the “Western” space of a perspective-based representation of reality – whose principles go back to at least the Renaissance – into an “Eastern” Slavic linguistic space that uses an alphabet whose origins go back to the medieval period in the Balkans, ?osi?’s birthplace. According to the artist, “the piece is dedicated to Mr. Danilo Ž. Markovic, the former Serbian minister of culture who once declared that ‘we all know that Cyrillic is not only the most beautiful script but also most suitable for work with computers.'”(?osi?, 3D ASCII, An Autobiography.)

So in a sense ASCII Unreal also performs a transcoding from one type of information to another, in the process disrupting and deconstructing visual codes and conventions we have come to accept as normal or even universal. This interplay between accepted “norms” or values and a more localized, specific view of reality lies at the heart of ?osi?’s artistic vision.

The iconography of computer games features in another work on show in Perth. The artist’s Game Flags (2009) consists of several banners hung in the streets surrounding the Threshold artspace building, taking the place of advertising for local theatre or music performances. These compositions in primary colors make visual puns in the manner of a word association game: works such as Tetriss or U.S. Invaders fuse scenes from popular early computer games with the ultimate symbols of national identity: the flags of nation states. The apparently simple act of turning the Stars and Stripes into a game of Space Invaders creates an incisive and multi-layered commentary on how the United States is perceived by many people outside of its borders.

The iconography of computer games features in another work on show in Perth. The artist’s Game Flags (2009) consists of several banners hung in the streets surrounding the Threshold artspace building, taking the place of advertising for local theatre or music performances. These compositions in primary colors make visual puns in the manner of a word association game: works such as Tetriss or U.S. Invaders fuse scenes from popular early computer games with the ultimate symbols of national identity: the flags of nation states. The apparently simple act of turning the Stars and Stripes into a game of Space Invaders creates an incisive and multi-layered commentary on how the United States is perceived by many people outside of its borders.

?osi?’s extends his interest in codification to other visual signs with his History of Art for Airports (1997-2009). He took both iconic and lesser-known images from the annals of art, simplifying and stylizing them to resemble the kind of pictograms found on lavatory doors. Many of the images are easily recognized, such as Cézanne’s The Card Players and Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Can. With characteristic irony, he explores how pictograms are a kind of universal visual language. Appropriately, this work is displayed on small screens installed in Threshold‘s public toilets, which the artist claims was the original environment for which it was designed.(Author’s conversation with the artist, Edinburgh, 3 August 2009.)

File Extinguisher (1998-2005) is ?osi?’s witty comment on the information overload that has become so familiar to Internet users. The artist claims to have uncovered original designs for a network that could withstand a nuclear attack. As he says: “Baran insisted that the true last line of defense of any distributed network would be a file extinguisher. However, he indicated this function with a red dot; due to the limitations of 1960s-era black-and-white printing, this key element was not visible in his publication. We can now recognize that today’s internet vulnerabilities are a direct result of this tragic mishap.”(Vuk ?osi?, File Extinguisher, (Ljubliana: Ljudmila, 1998-2005), http://www.ljudmila.org/~vuk/file-extinguisher/. See also Paul Baran, “On Distributed Communications,” in Rand Memoranda, vols. 1-11. (Santa Monica, California: Rand Corporation, August 1964).)

Through this faux historical footnote, ?osi? thus ascribes the Internet’s current status as a global digital archive to an accident. The artist’s humorous and obscure slant on notions of human technology’s fallibility implies that there is something fundamentally wrong with the online utopia we have been trying to build. Seeking to correct the imbalance, he invites the viewer to delete some of their own data from the network permanently using his File Extinguisher. This simple destructive act is tantamount to a Dada inspired cry against the orthodoxies of conservation and archival beloved of network administrators, librarians, and museum curators.