The Hungarian Patient: Comments on the “Contemporary Hungarian Art of the 90s”

Two years ago, when the editor of a Hungarian academic journal in art history asked me to write about “the contemporary Hungarian art of the 90s,” I agreed to do so without the slightest hesitation, and proposed a paper on the changes of the institutional framework of the period. Later, when I was setting off to research, I realized that none of the components of the apparently innocent phrase “the contemporary Hungarian art of the 90s” was clear enough to be taken for granted.

How could we define the period of the 90s and the generally established category of contemporary art in the Hungarian context? Do we know what we mean by “Hungarian” or by “art”? The disturbingly simple, but nonetheless unavoidable questions I had to face resulted in a paper which, though it also includes elements of the proposed analysis, starts by questioning and exploring the terms that have been intended as a subtitle of the essay.

Timelines

When can we begin to speak about the period of the 90s in Hungary? And where are we to posit the end of it?

It is quite reasonable to put the beginning of the last decade at 1989, the year of several important political events such as the reburial of Imre Nagy, the executed prime minister of the revolutionary government of 1956, a funeral which put a symbolic end to the Kádár régime, the proclamation of the Third Hungarian Republic, and the termination of the Warsaw Pact which, at least from a politico-military point of view, abolished the Soviet block.

Apparently confirming this choice of a starting point, the Hungarian collection of the Ludwig Museum of Contemporary Art in Budapest also covers the post-1989 period, as do the press and the political rhetoric which date the changing, or as the conservative Hungarian media likes to call it, the alteration of the regime at this year.

Nevertheless, to assign the origin of the 90s to 1990, the year of the first free election of the post-Kádár period and that of the fall of the Berlin wall, seems equally accurate. Crucialevents within the Hungarian art world were taking place also in this year.

It was in January 1990 that the monthly art magazine M?vészet (Art) transformed into Új M?vészet (Art Today), and with Péter Sinkovits, an art critic and a once important figure of 1960s neo-avantgarde, as editor-in-chief, the magazine became a leading, yet still open forum for various artistic discourses and debates.

It was also in this year that the Ludwig Museum of Budapest, the first substantial collection of 20th- century European and American art in Hungary, was opened to the public in the former building of the Museum of Worker’s Movement, and that the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts underwent an important, although controversial series of structural reforms, which many often called “deforms.”

The reform initiated the teaching of new media art and made it possible for several formerly banned and marginalized artists of the Hungarian neo-avantgarde to occupy academic chairs. It was also around this time that the old distinction between official and non-official art lost its meaning, at least for a short time before it once again became evident that such a distinction is less of a régime-, or period-specific phenomenon than it first appeared.

As for the end of the 90s, the year 2000, during which significant art exhibitions surveying the East European region were presented in Europe and also in the Ludwig Museum of Budapest, seems not only an obvious but also an adequate choice. It seems that by conceiving and sponsoring exhibitions such as the After the Wall (Moderna Museet, Stockholm), the L’autre moitié de l’Europe (Jeu de Paume, Paris), and the Aspekte-Positionen (Museum Moderner Kunst, Vienna), art historians and critics based in the EU member-states put an end to the 90s of the former Soviet block.

The mega-shows of the millenary year not only tried to take the advantage of the remains of the rapidly vanishing vogue for Central-Eastern Europe, but also, with less success, attempted to reanimate the former interest in the region. After these region-specific exhibitions, the cultural boom and the attention to Eastern-European art as such has definitely come to an end.

But the end of the decade could also be dated to the last third of 2001, to the period that followed the 9/11 attacks against the US. As this date represents the more and more transparent emergence of a new power politics evoking the rhetoric and the praxis of the Cold War, and also the slow, yet sure arrival of a global economic recession, it defines the end of the 90s more characteristically than the year 2000.

In the cultural and political discourse, the epoch of the 90s in Central Eastern Europe, similar to the years of sovietization in 1947-49, is often represented as a “period of transition.” Despite the particularity of the last decade, clearly marked by traumatic political and economical changes, we need to ask, at least rhetorically, whether these changes have been accompanied by equally characteristic and perceptible changes in the field of culture.

As the practice of contemporary criticism and the experience of art history have often proved, decennial surveys are not necessarily instructive for understanding and analyzing a given period, nor do specific artistic developments tend to follow decennial patterns. The transitions of the contemporary art scene of the 90s in Hungary do, nevertheless, largely follow the mechanisms of the political and economical changes, enabling us to explore them as an aspect of the so-called “period of transition.”

What we mean by “contemporary”?

Having fixed the limits of the period, we are faced by the basic and frequently asked question: How does the term “contemporary art” relate to the entire artistic and visual production of the decade, or, to put it slightly differently, what do we mean by saying “contemporary art” when talking about the artistic production of a recent period?

Questions about the difference between contemporary art, which usually functions as a value-category, and art produced by contemporary artists relate to the specific position of the “progressive” art in the pre-1989/90 period, which either was tolerated or prohibited, but by no means supported, by the then prevailing cultural policy of the Kádárist state. The notorious system of the three categories (supported, tolerated, prohibited) drew the line between official and non-official art, and also gave rise to the phenomenon of “second publicity.”

With the aid of progressive critics and intellectuals, tolerated or prohibited works and artists, i.e. those who belonged to the overlapping categories of second publicity and non-official art, forged their identity on the basis of the ethos of a politically resistant avant-gardism and of a presumed artistic excellence.

In this context, being officially prohibited came close to being understood as being a neo-avant-garde like protagonist of both social and artistic progress. No wonder that during the 90s, with the disappearance of political censorship and of the boundaries between official and non-official art, questions about the evaluation and the hierarchy of art came to the fore.

As critic Gábor Andrási remarked, the term “contemporary” art does not refer to works of artists working simultaneously in a given period of time, but to the production of those who once were described as “radical” or “progressive,” regarded today as “mainstream” artists, and who are being privileged and canonized within a given scene.(Cf. Andrási, Gábor, “Mi a mamco! (Örök katzenjammer)”, Nappali ház, 1998. n. 4., pp. 87-88.) And it is, of course, through the system of institutional and of critical references and legitimizations that someone does or does not fall into the category of “contemporary art.”

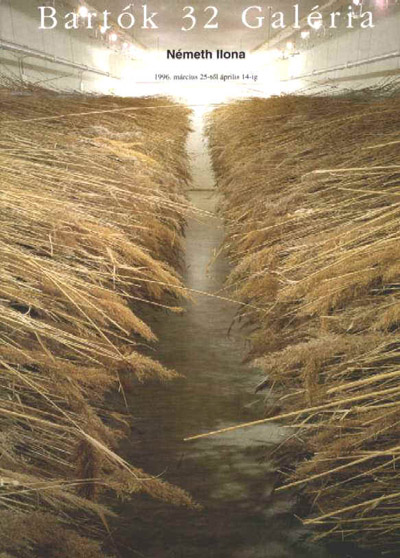

Obviously, it is still the institutional theory of art that comes most handy when one tries to settle the notion of contemporary art. In Hungary, those who are, or recently were regularly showing their works in the Project Room of Ludwig Museum, in Studió Gallery, in Trafó, in Knoll Gallery, Liget Gallery, Bartók 32 Gallery, or Óbudai Társaskör Gallery, or in MEO, and in the French Institute, belong without reservation to this category.

Those whose works were shown in Ernst Museum, M?csarnok (Kunsthalle), Dorottya Gallery, Ludwig Museum, Goethe Institute, and private galleries, or found their way into the collections of various banks and corporations, do not necessarily fit into it.

As institutions and institutional references and legitimizations are obviously responsible for sustaining the contemporary art world, their lack leads to deficiencies in the representation of contemporary art. In Hungary, where the institutional network of art is almost entirely concentrated in Budapest, this seems to be palpably true: Beyond the museums of Székesfehérvár, which has traditionally been devoted to the representation of contemporary art, Little Gallery of Pécs, the ICA of Dunaújváros, which was opened under the direction of Lívia Páldi and János Szoboszlai in 1997, and occasionally the Picture Gallery of Szombathely, there are no other places for one to either see or show contemporary art in Hungary.

What is Hungarian?

Writing about “the Hungarian contemporary art of the 90s” still requires clarification of whether we think about “the Hungarian contemporary art of the 90s” or “the contemporary art of the 90s in Hungary.” Given the unfortunate local traditions of cultural monopolization (to put it rather euphemistically), this question is far from a rhetorical one.

If a 1999 book, Hungarian Art in the 20th Century(Andrási, Gábor-Pataki, Gábor-Sz?cs, György-Zwickl, András, The History of Hungarian Art in the Twentieth Century, Budapest, Corvina, 1999.), had not compelled us to once again think over this rather dubious adjective phrase, we could easily skip the following and settle with the “in Hungary”-version, acknowledging the priority of the cultural and social context of the production of works as opposed to the national and ethnic affiliations of their producers.

The volume, which aims to complement and to supersede its 1968 predecessor, Lajos Németh’s Modern Hungarian Art, was written by four prestigious Hungarian art historians and published as a textbook for students of art history. If the title of the handbook (at least in Hungarian) was indeed chosen to follow and to refer to Németh’s 1968 book, there emerges the question of whether the authors realized the difference between the significance, or even appropriateness, of such a title in 1968 and in 1999.

While in the Kádárist Hungary of the late 60s, the title Modern Hungarian Art (as well as the book itself) was considered a subversive one, which problematized a prevailing, nostalgic, mid-19th century concept of national art and independence. The adjective “Hungarian” in the title of a 1999 publication which includes Hungarian artists living outside the borders of the country, and thus defines its scope simply by ethnicity, reflects a reliance on unexamined and critically unproductive premises, not to mention the latent politics of such definitions of Hungarian art.

This becomes all the more striking in the English edition of Hungarian Art in the 20th Century where references to the places of birth of artists born in the neighboring countries are deliberately given as Transylvania and Vojvodina, without the slightest allusion to the proper name of a given country.

The Slovakian-Hungarian artist Ilona Németh, who represented Slovakia at the Venice Biennale in 2001 and who also regularly exhibits in Hungary, appears in the book without explaining that she was born in Slovakia or that she is based in Dunájska Streda, Slovakia. All this is too closely reminiscent of a typically early 20th century, but today untenable routine, which, by a patronizing, monopolizing gesture, included artists of Hungarian nationality living in the neighboring countries into “Hungarian art” without the slightest reservation.

But the question “What is Hungarian?” also raises another issue: Does contemporary art in Hungary have specific characteristics that make it obvious that they belong to the contemporary cultural and social practices of this particular country? It comes as no surprise that similar interrogations seem to occupy a substantial place in the contemporary critical writing in Hungary from the mid-90s on.

There as been an increasing number of international contemporary shows presented in Hungary. There are more and more, though still insufficiently accessible, exhibition catalogs, books, and periodicals of the multilateral exchange programs and residencies. And as a result of this, as well as the internet and the expansion of the new communication technologies, during the 90s, for the first time in decades, artists, critics, and audiences had the opportunity to see works of the local and international scene together, and thus to form a relatively accurate picture about what has been done here, in Hungary, and what has been done elsewhere.

Some of these works are dealing with the geographical, cultural and/or ethnic affiliation of their creators thematically, and in a clear and distinct way. It suffices to think about the films of the New York-based Persian artist Shirin Neshat, the photographic series on coal-miners of the Ukrainian Arsen Savadov and Georgij Senchenko, or the manga-like fantasy-prints of the New York- and London-based Japanese artist Mariko Mori.

It seems useful to add, however, that in the works of Shirin Neshat, to mention just one of the previous examples, it is not Iran or its Muslim culture that is represented, but rather the relationship between Iranian women and Muslim culture – and presumably, there is no need to argue that these are far from being the same. This case also shows that the representation of national, linguistic, or cultural identities could not be differentiated from other constitutive aspects of identity-formation, such as, in this case, the issue of gender.

But by calling for, as many critics do, the representation of some dubious “Hungarianness” in contemporary art works in Hungary, would we not limit the formulation and the representation of identity to a single and indefinitely general category? And how could “Hungarianness” or the specificity of contemporary art in the country be represented, if at all, without implying the stereotypical images of the mysterious wild-and-woolly East, of some supposedly special Eastern European sensitivity, or of the glorification of Hungarian paprika?

Is it possible to-and why indeed would anyone want to-represent difference without also packaging it for transnational consumption? How is it possible to avoid the tendency in which artists in Hungary would, with the self-colonizing eagerness of those living on a periphery, identify themselves as anthropological subjects in relation to an alleged or actual, and less and less localizable, center? And if that happens, does it take them closer to a less and less definable mainstream? Or rather, does it produce new forms of provincialism?

On the other hand, a comparison of the works produced in Hungary and elsewhere makes us also realize that there is less difference between young urban artists from Hungary, Poland, Brazil, or Great Britain than we would possibly expect. How could it be an effortlessly definable difference, if, – due to the global models of metropolitan consumerism, the overall similarities of the social and cultural contexts, and of the perception of a largely related world – they all watch the same movies, read the same art magazines, and use almost identical cell phones?

How could the specificities of a language, a culture, a region, or a country be mapped out among works of a Hungarian, a Polish, a Brazilian, or a British artist within a globalized art world? How Hungarian is the art of Antal Lakner or of Hajnal Németh? And how Scottish is the art of Douglas Gordon?

Indeed, how do we know that Janet Cardiff is an English-speaking Canadian, or that Pierrick Sorin is an artist of Breton origin if not from the biographical data of their exhibition catalogues? Or, how is “Polishness” represented in works by Zbignew Libera or Katarzyna Kozyra?

Without wanting to advocate one of the basic products of global capitalism (the concept of transnational identity), when demanding nation- and context-specific characteristics of contemporary works, either in Hungary or elsewhere, we must ask ourselves: are we not following, maybe unawares, a cultural and art historical tradition which, from Riegl through Panofsky or the Hungarian Tibor Gerevich to Chastel, invested national character and local specificity with primary interpretative power in the analysis and the explication of works of art?

On the other hand, we must also be aware that when arguing for some transnational identity, we often run the risk of promoting a modernist pseudo-universalism and ideology of happy globalism. And we need to take into consideration not only the global-theoretical, but also the local-political significance of our expectations in a world where nationalisms and ethnic segregation seem to be the increasingly ascendantreaction to globalization.

In Hungary, where even young contemporary artists were socialized under the pressure to keep up with the prevailing trends of Western art and to try to obtain the endlessly pursued simultaneousness with the center, the above mentioned questions seem particularly pertinent.

Thus, when critics and historians of the region are calling for graspable regional, cultural, and social specificities in the works of local artists, they also have to explore and redefine the modernist Eurocentric matrix of East and West as periphery and centrum together with the concept of Central Eastern Europe as “the near Other” (Boris Groys) of the West and with the still prevailing attitudes of self-colonization.

Parallel Narratives

In the fortunate lack of a prevalent master narrative, the art of the 90s in Hungary could be mapped out according to various approaches and interpretations.(Cf. Andrási, Gábor, “A modernizmuson túl, generáció es szemléletváltás a kilencvenes évek magyar m?vészetében”/”Beyond Modernism, New Generations and Shifts in Perspective in the Hungarian Art of the 90’s” In: Omnia Mutantur, XLVII. International Biennale of the Visual Arts, Hungarian Pavilion, exhibition catalogue, eds. by Edit András and Anna Bálványos, Budapest, Kortárs M?vészeti Múzeum-Ludwig Múzeum, 1997, pp. 13-16; Kovács, Ágnes, “The State of the Art : Hungary”, Artmargins, 1999; Snodgrass, Susan, “Report from Budapest: In a Free State”, Art in America, October 1998.) Reading it along the classical concept of period styles and genres – as the dominant art historical discourse did in Hungary until the early 90s – would lead us to the journalistic conclusion that the works of our period are disturbingly disparate.

As in the global art scene, in Hungary it was also during the 90s that installations, video-based, and new media works became widely used, that figurative painting returned with a vengeance, or that the visual rhetorics of popular culture and of the advertising industry appeared as major points of reference in works of contemporary art.

Reading the art of the 90s in Hungary along trends would not offer more than an utterly non-sensical and confusing process which, even in spite of an appropriate conceptual system, would oblige us to stick with such multiplying compound notions as post-post-concept art, neo-neo expressive, neo-hyper-real, neo-neo-dada, and neo-neo-pop.

Nevertheless, offering no more then a preliminary list of the characteristics of the 90s scene in Hungary, we could enumerate the following new phenomena: (1) the dominance of techniques and issues related to appropriation, copying, and recycling; (2) the growing interest in representations of gender, mainly among women artists, which took place in parallel with the slow recognition of the constructedness of identities; (3) the rise of works operating in the bordering spaces of fashion, film, and music; (4) an increasing number of interactive- and sound-installations; (5) the emergence of works by multiple authors and of the questions of artistic cooperation and authorship; (6) the coming to the fore of works dealing with the social context and with the criticism of artistic institutions and that of the media; (7) the appearance of works engaging in the representation and in the deconstruction of the body.

Among the most important transformations of the epoch one should also note that women artists started to gain ground in the formerly almost exclusively male-dominated mainstream and the redefinition of the functions and the modes of public art. But instead of such an elementary enumeration of genres, techniques, and trends, when trying to frame the art of the 90s in Hungary, we ought rather turn to art criticism, to the institutional network and to art trade for orientation.

The Remains of Criticism

Before exploring the Hungarian criticism of contemporary art and visual culture, it is useful to ask where reviews and essays on art are usually published. Beside the already mentioned Új M?vészet, three other monthly magazines publish criticism and various contemporary art-related materials on a regular basis: Balkon, which, since his first issue in November 1993, operates under the editorship of István Hajdú and engages also in the study of theater and contemporary music; Exindex, an electronic journal of C3 (formerly known as the Soros Center of Contemporary Art), directed by József Mélyi; and the separately published monthly paper M?ért?, owned by the prestigious economical and political magazine HVG, whose editor-in-chief, Gábor Andrási, undertook the job to cover the contemporary scene in its entirety, and thus expanded the initially collecting- and trade-centered focus of the journal.

Occasionally, writings on contemporary art and visual culture appear in other publications, such as Beszél?, a rather highbrow political and critical monthly; the glossy art magazine Oktogon, in the leftist alternative cultural political weekly Magyar Narancs, in the Hungarian edition of Playboy and Cosmopolitan, on a few Hungarian internet journals like Index or Korridor, and also in the extreme right monthly art magazine Magyar M?vészet.

Yet, major daily newspapers and television channels, including public television like Duna TV, and the widely read cultural and political magazines hardly, if ever, deal with contemporary art.

According to the wildly accepted explanation, the lack of media coverage and general attention toward contemporary art is a consequence of the inferiority of arts and of visual culture compared to literary and musical culture, which in Hungary, have played a leading role in the formation of national identity since the early 19th century on.

This explanation, however, does not take into consideration that visual and artistic culture, as well as its place within a given society, is far from being constant and immutable, and that in the history of the country, there were periods when despite its secondariness, art and art criticism functioned as a dialogic and open field of cultural and social discourse.

While thinking about the state of criticism of contemporary art in Hungary, one question comes unavoidably to the fore: Who was writing about art and visual culture in the 90s? Who are and were the critics in Hungary? As a consequence of the weak representation of contemporary art scene in the major daily newspapers and on television, the number of professional critics (i. e. people who earn their living by writing about art) is virtually nil.

Those who write criticism are either art historians, or, according to the ordinary but highly questionable term, “writers in art” (i.e. people without a degree in art history). This separation tells much about how the discourse on art and visual culture limited itself into the so-called, alleged or actual, “professional” field, and produced the otherwise widely protested isolation of the art scene.

The praxis of “stick to one’s last,” which also reveals how unaffected the Hungarian discourse is by interdisciplinary methods, is founded on at least two improper assumptions: first, that the professional, i.e. the art historian, is competent in contemporary art and criticism, and second, that in dealing with contemporary art and in doing criticism, someone definitely needs a degree in art history and all the additional competence that comes with it.

Presumably, it does not require supplementary explanation why none of these presumptions is maintainable. At the two Hungarian art history departments, contemporary art is barely, if at all, discussed, and those interested in it are never obliged to do any written assignment that could be at least remotely called a review or critical study.

But, one might ask, what kinds of texts we are speaking about when it comes to the criticism of contemporary art and visual culture in the Hungary of the 90s? One part of the corpus focuses on the evaluation of the works, either in the form of eulogy, or less frequently, in that of disparagement. Criticism on both poles of this binary seems to be written in the firm belief that it is guided by objective criteria and clearly formulated normative expectations.

Another group of texts is confined to the description and to the formal analysis of the works at issue, without the exploration of artistic, intellectual, social, and political contexts of works, artists, and exhibitions. And there are very few texts,which, by different methods and ways of questioning beyond the scope of formalistic approaches, are analyzing and commenting on works by focusing on their reception in the field of cultural production, in the context of artistic and social practices shaping them, or on the intellectual and theoretical biases involved in their construction of meaning.

These frequently politically charged texts often received rather skeptically or with overt animosity, are trying to reflect on and to enter into dialogue with various theoretical and social discourses which mostly emerged in the field of cultural studies and of critical theory. And, as the local contemporary scene amply produces works that, consciously or not, imply these discourses, the rarity of adjoining texts creates a disturbingly dissonant situation.

Besides a few exemplary cases such as the exhibitions Polifónia (Poliphony, 1993)(Polifónia: A társadalmi kontextus mint médium a kortárs magyar képz?m?vészetben / Poliphony: The Social Context as Medium in the Contemporary Hungarian Art, exhibition catalogue, eds. by Barnabás Bencsik and Suzanne Mészöly, Budapest, SCCA, 1993.) and Vízpróba (Waterordeal, 1995)(Vízpróba a kortárs magyar (n?)m?vészeten,( n?)m?vészeken/Water Ordeal on the Contemporary Hungarian (Women) Art and (Women) Artists, exhibition catalogue, eds. by Edit András and Gábor Andrási, Budapest, Óbudai Társaskör Galéria, Óbudai Pince Galéria, 1995.), artistic practice and criticism are hardly in accordance with each other. But critics and art historians working in the field of contemporary art and culture are certainly not the only ones to be blamed for all that: It is hard to write a theoretically and historically informed criticism if the Hungarian reception of theories and practices associated with contemporary cultural writing are almost completely missing.

Not that their reception or integration would be easy to accomplish, but without doing it, we would not have anything but the misinterpretations, and the not necessarily productive misunderstandings and the overestimations; in brief, the consequences of belated reception.(See András, Edit, “Who is afraid of the new paradigm?”, lecture delivered at the AICA conference in Zagrab, October, 2001. Published in Hungarian: M?ért?, December 2001, also in English see ARTMargins; András, Edit, “Fájdalmas búcsú a modernizmustól, Az átmenet id?szakának terhei”/”A Painfull Farwell to Modernism, Difficulties in the Period of Transition” In: Omnia Mutantur, XLVII. International Biennale of the Visual Arts, Hungarian Pavilion, exhibition catalogue, eds. by Edit András and Anna Bálványos, Budapest, Kortárs M?vészeti Múzeum-Ludwig Múzeum, 1997, pp. 26-29. and After the Wall, Art and Culture in Post-Communist Europe, catalogue exhibition, vol. I., Stockholm, Moderna Museet, 1999, pp. 125-130.) Of course, belated reception is still better than none at all: For the result of that is frustrated provincialism.

Contemporary Art and its Institutions

It was also in the 90s that institutions of contemporary art were either established or transformed into their present-day forms. When speaking about the institutions of contemporary art, we think about museums which are, at least partially, specialized in contemporary art: Non-profit and commercial galleries, as well as foundations, artists-based projects and places, artistic associations such as the highly heterogeneous Hungarian Art Foundation and the National Association of Hungarian Artists, and the institutions of art education such as the Academy of Fine Arts and the Academy of Applied Arts of Budapest, and the University of Fine Arts of Pécs, which was founded in 1990.

The National Cultural Fund, which, since its 1993 establishment, has undergone several major changes, has a primary role in the distribution of government funding, and thus controls almost the whole sphere of the mostly government subsidized contemporary art. Similar to the neighboring countries in the funding and the forming of the 90s contemporary art scene, the Soros Foundation, along with the former Soros Center for Contemporary Art, played a decisive and a greatly beneficial part, which, since the transformation of the latter into C3 (Center for Culture and Communcation) in 1996, has unfortunately diminished.

Among the museums and major exhibition halls dealing with local contemporary art, the solo exhibitions of the Ludwig Museum’s Project Room, the Kunsthalle’s thematic group exhibitions of emerging contemporary artists, the events of the ICA-D (Institute of Contemporary Art of Dunaújváros), and a few solo exhibitions of the MEO Museum of Contemporary Art, a recently opened private institution, contributed largely to the formation of artistic and cultural dialogues.

However, the activity of the contemporary art scene in Hungary is primarily represented and shaped by the mostly government or municipal funded non-profit galleries. Beyond the central resources, an important segment of the funding of the non-profit sector is provided by foreign cultural and diplomatic institutions and foundations such as, for example, the Pro Helvetia Foundation which in 1996 contributed to the setting up of the League of Non-Profit Art Spaces.

Within the network of institutions, or rather in opposition to them, the first part of the 90s was also an epoch of artists-based, semi-private projects. The Újlak Group organized exhibitions and events between 1989 and 1995, first in the abandoned Hungária Turkish bath, then in the Újlak Cinema, and finally in a deserted factory in T?zoltó Street. The activity of the group quickly became a model for other early-90s artist-based initiatives such as the Törökfürd? (Turkish Bath), or the M?terem (Studio), a miniature experimental gallery which was run by the painter Tamás Kopasz.

Parallel with the emergence of non-profit and private galleries, from the mid-90s on these non-institutional projects came to an end. For a short time, it seemed that the moderate boom of both non-profit and commercial galleries could substitute for these “hidden,” yet primarily important places, offering to the formerly participating artists and also to the newcomers a more rewarding possibility to be present in the scene. Then at the end of the decade, certain artists-based initiatives began to reappear with the aim of opening up the field of contemporary art for a broader public and dialogues.

Among the recent and utterly miscellaneous ventures we find Index, a free bimonthly brochure on the events of the contemporary scene in Budapest, a publication started by two artists, Attila Ménesi and Christoph Rauch as an exhibition project in 1999; Ikon, an art listings service and a searchable online database which was initiated by the artist Endre Koronczi in 2000 (www.index.hu); Kis Varsó (Little Warsaw), a by-invitation-only exhibition and discussion place run by the artists András Gálik and Bálint Havas; and the kmkk collective (Two Artists, Two Curators) in 2001 by two artists (Róza El-Hassan, János Sugár) and two curators (Dóra Hegyi, Emese Süvecz), which inaugurated a diverse project consisting of exhibitions, film screenings, and lectures.

One of the most interesting, and certainly the less institutionalized, newcomer on the scene is Manamana, an irregularly published anti-globalist, cultural and political fanzine, created by the artists Tibor Várnagy and Miklós Erhardt in 2001.

Undoubtedly, since the beginning of the last decade, the most dynamic agent of the scene was the Studio of the Young Artists Association and its gallery, the Studio Gallery, which since its 1990 foundation became the primary exhibition space for young, emerging artists. The Studio Gallery, first directed by Barnabás Bencsik, then in 1999 by Edit Molnár, has been the first artist-based collection that, in a semi-institutional form, organized international exchange and residency programs, as well as exhibitions, round-table discussions, an annual week-long series of one-night exhibitions called “Gallery by Night,” and a week-long series of various artistic events called “Mind the Gap.” The Studio was also one of the main generators in the initiation of thematic exhibitions and of the development of the curatorial system in the country.

The one-person institution of the curator, represented by a new generation of critics and art historians, appeared parallel with artistic practices aiming to rewrite or to neutralize authorship, and to reflect on the social status of the artist. While curators working in the leading Hungarian institutions of art become as important – if not more important – players in the system as critics or art historians,(On curators and curatorial exhibitions in Hungary see: Szoboszlai, János, “Selbstbildnis einer Generation (Self-Portrait of a Generation)” In: Die zweite Öffentlichkeit. Kunst in Ungarn in 20. Jahrhundert, hrsg. Hans Knoll, Dresden, Verlag der Kunst, 1999, pp. 324-327.) explicit reflection on the practices of curatorship and on the politics of exhibitions have not yet emerged in the scene.

The fact that questions about the role and the power of curator or about retaining power positions within the major art institutions and funds are still waiting to be asked shows that the non-profit, or artist-based institutions, despite their dominant role in the scene of art, are scarcely capable of articulate voices of reflection and opposition.

Buy and Sell: Contemporary Art, Trade, Private Sphere

In Hungary, one of the most important developments of the 90s was the fact that professional art trade had started again. Of the private galleries that began to appear more or less regularly around 1990, the recently opened MEO Museum of Contemporary Art and the A.P.A. (Atelier Pro Arts) are the most significant art institutions of the private sphere.

These profit-oriented establishments are playing a decisive role in canon-formation and in shaping public taste. The fact that in the face of constant financial difficulties they could still survive shows that a market for contemporary art has slowly appeared in the country due to, among other factors, the rise of a new, far from homogenous elite whose life style involves the consumption and collection of art.

However, like the whole contemporary art world, this market is a rather slow and small one, and for the most part, its customers still come from the personal acquaintances of the artists. As the public of the contemporary art is dominantly composed of critics, art historians, and artists, i.e. of the financially insignificant agents of the scene, customers, or potential customers could hardly be found in the public.

It is at this point that the task and the interest of the critic, the museum worker, and the gallerist converges in the development of art education, of mainstream media criticism, and of public program organization in Hungary.

As a result of the presence of large national and multinational corporations in the country, the patronage and the financing of contemporary art has significantly, yet still insufficiently, increased during the last decade. Banks and other corporations reached out to contemporary artists, and they not only buy, but also exhibit and promote their works, sponsor the publication of their catalogues, or, as in the case of the leading construction firm, Magyar Aszfalt, they announce competitions and prices.

But, the occasional purchases of the Hungarian oil company MOL, and of banks like the OTP, the Raiffeisen, or the Dresdner, to name just a few, create visibility and financial support only for a few contemporary mainstream artists working in traditional media like painting, sculpture, photography, and digital print. Some of the leading types of production of the contemporary scene, such as installations, objects, videos, sound-installations, have obviously no place either in the lobbies of banks, or indeed in the white cube spaces of private galleries.

Consequently, the majority of the works of the scene, as hardly saleable products, are excluded from the market, obliging artists to work double, producing video-installations for non-profit galleries, for critics, and for their portfolios, and to earn a living by producing marketable pictures to hang on the walls of corporate offices.

In Hungary, private galleries frequently appear in the texts of both critics and artists as the token of the well functioning and flourishing art world, and it has been suggested that their further proliferation could only generate long desired discourses and dialogues on art and visual culture.

Unfortunately, the widespread overestimation of the role of private galleries, a fantasy modeled on the examples of the New York, London, or Berlin art world, not only mythologize the role of these institutions, but also overlook other, and in the local context, much more important issues and deficiencies of the scene, such as the scarcity of artists-based collectives, or the above mentioned hiatuses in public education, in art criticism, and in audience canvassing. Another, more pressing question is how the presence of these private establishments will affect the work of the non-profit institutions and artist-based projects or museums of contemporary art in the future.

Instead of further questions or conclusions, I would like to stop here, at the point where thinking about works, artists, and events could begin.