Special Section Focus: Public Art in Hungary

|  |  |  |

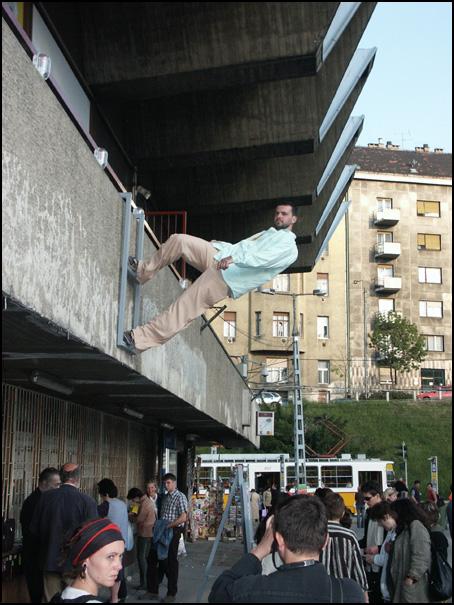

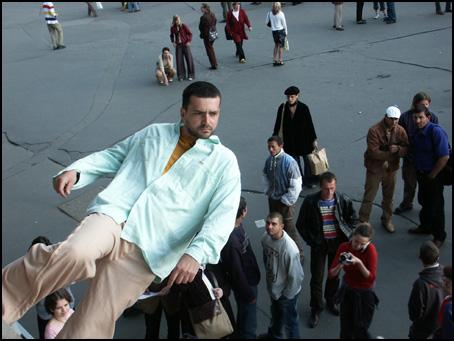

On Moscow Square, Budapest, it is the morning rush hour.(I would like to thank Edit András and Tyrus Miller for discussion and revision of my text.) A young man appears to be walking on the wall of the subway station building, defying gravity. Those who had arrived earlier and stayed till the end of the performance, of course, already knew the trick: A metal construction, concealed by his clothes, sustaining him, making it a real spectacle.

People stop a minute, stare up, guess at what he is doing and why; others take no notice at all and pass on indifferently. Beneath him, in front of the building, the assistant of this art performance Tyborman (referring to spider man) distributes a questionnaire soliciting the opinion and suggestions of the audience and some spectators take time to fill it in.

The questions refer mainly to what people think this Tyborman is doing, how long they think he will do it, and how his actions could be made more interesting and appealing. Some people suggest he should shout for help or distribute candies; others offer offensive suggestions. The artist, Tibor Gyenis (b. 1970), sorts through the recommendations and uses them the following day.

Three times a week he risks his own skin by undertaking a physically demanding task and subjecting himself to the unpredictable reactions of his spectators. The title of the work also refers to another comic book and film “superhero,” Superman. But this superman is without supernatural abilities, without fame and popularity among the “simple” people.

He is not identifying himself either with the virile male hero, or with traditional patriarchal values. He is rather fulfilling the criteria that psychoanalyst Theodor Reik, philosopher Gilles Deleuze, and recent writers on performance and visual culture identify for the enactment of masochism or, more precisely, masochistic spectacle.

Gyenis keeps himself in the mode of suspense both literally and metaphorically, for he does not move for 45 minutes. Thus immobile and precarious he stimulates the audience’s anxious fantasy to imagine how his performance will proceed, what could happen next.

He provokes the fears and derision and wonder of his audience, the spectators and passers-by with whom he forges a quasi-contract for the coming day’s events. He wittily plays with the heroic notion of the artist: The artist as superman, the chosen one, with art’s vaunted ability to prophesize the future, and also with the notion of the eternal work of art (he is a mortal living sculpture) as a monument elevated high above the ground.

Gyenis thus effectively intervenes in the everyday life of everyday people, interacting with a public that in large part never goes to see art in a museum.

Public art in Hungary under socialism meant, in practice, sculptures, and mostly in open air spaces, parks, streets, on the walls of public buildings. Art was given to the people by the privileged artists, and it served first of all “cultural policy”.

The socialist state commissioned the works, and the commissioned artists had to be politically trustworthy. This did not mean that the artist necessarily was a party member, rather s/he accepted the conditions of having an artistic career in the given circumstances. Art and politics seem to have preserved their mutually suspicious relationship.

In the post-socialist countries, “politics” is mostly understood in a very restricted, governmental, “party-and-state” sense of the word. Yet whereas artists in some of the former socialist countries are already confronting politics in a broader sense, including issues of identity, gender, ethnicity, and power relations in language and everyday life, only a few Hungarian artists have begun to deal with political issues in this wider sense.

It is telling that the Hungarian term “public art” is reluctantly used, since it remains saturated with the propagandistic overtones of the previous epoch.

The idea to organize a public art event in a busy public space of Budapest originally came from an artist, Róza El-Hassan (b. 1966) who, partly because of her own personal history and identity, has taken up politics in this broader sense: Identity politics and topical, often sensitive social and political issues.

She wanted to make art more visible and accessible for a larger public. The present show Gravitation, which included a work by El-Hassan and others, was realized with the help of the European Union’s Culture 2000 program, the Hungarian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and the Cultural Committee of the City Municipality of Budapest. It was organized by Ludwig Museum Budapest-Museum of Contemporary Art.

To be fair, the Moscow square project did not come out of the blue; it has its predecessors. In 1992, for example, Tamás St. Auby covered the symbol of the Soviet regime, the Liberty Statue overlooking the Danube, with a white shroud, thus converting an iconic public sculpture to a ghost floating above the city of Budapest (an intervention conceived by Júlia Lorrensy).

A year later, Suzanne Mészöly, the ex-director of the Soros Center for Contemporary Arts (later C3, Center for Culture and Communication, Budapest), initated Polyphony: Social Commentary in Contemporary Hungarian Art. This included site-specific works, installations, documentation, and a symposium. A thick published volume closed the series of events.

To make and present socially involved art in 1993, only four years after the fall of the Wall, had its risks, for it could be labeled “politically engaged”, and in the context of those days, this was a negative tag. Through an open competition, Polyphony created an opportunity for artists to present their socially involved projects. It realized a series of up-to-date events, paralleling the current phenomena in international art that focuses on social problems (Whitney Museum of American Art’s 1993 Biennial Exhibition, Creative Time’s 42nd street Project, 1993).

However, a ten-year break ensued in the history of socially involved, issue-based public art in Hungary. There were various attempts to bring art closer to the public, like a group of young artists around 1999 who wanted to make “real” art for “real” people.

Endre Koronczi set up an on-line site, Ikon, that includes all the information, dates, openings, events of the art world. Attila Menesi and Christopher Rauch initiated Index, a gallery and museum information leaflet, thus making information of the art world, a small, select elite available for everyone.

The exhibition Services (2001, Mûcsarnok, Budapest, curator Judit Angel), Budapest Box (Ludwig Museum Budapest-Museum of Contemporary Art, curators Dóra Hegyi and Katalin Timár), a workshop around the topic of public art organized by Emese Süvecz last November, and last but not least the works of Tibor Várnagy and Miklós Erhardt should be mentioned.

These last two have been making socially engaged art works since the nineties (see interview).

All these were the precursors of the present, ambitious project, Gravitation or Moscow Square (Moszkva tér, Budapest, May 16 through June 29, 2003, curator Dóra Hegyi).

Moscow square itself is a busy junction of very different parts of the city of Budapest. Homeless people spend the night there, drug dealers and addicts do business there, and a busy subway stop is located under the square. For many of the inhabitants of the elegant and rich neighborhood surrounding it, the square is the beginning and end station of their public transportation.

Very close to the square there is an up-scale shopping mall, and many tourists take the bus from here to get to the historic castle district. It is also a living meat-market, for a lot of illegal aliens gather here in the mornings waiting to be picked up for a day of work at a construction site.

There is an active trade in flowers, clothes, and other goods being sold by street vendors. It is a meeting point of the rich and the poor, of foreigners and locals. The name of the square itself bears history, since it got to be called Moscow square in 1951, during the strictest period of the totalitarian Stalinist regime. Unlike many of the streets and squares in Budapest, it was not renamed after the collapse of the regime in 1989.

The participants and the works of the Moscow square project were selected by a board appointed by the Ludwig Museum. They invited the Hungarian artists Róza El-Hassan and Balázs Beöthy. TNPU, St. Auby, the group of artists Little Warsaw, and András Gálik and Bálint Havas, who represented Hungary in the 50th Venice Biennial.

They also selected works from the advertised competition (Ilona Németh, János Sugár, Ágnes Eperjesi, Tibor Gyenis, Andreas Fogarasi, Sándor Bartha, Ágnes Eszter Szabó and Mónika Bálint, Sándor Bodó, and an anonymous artist via email) and invited foreign artists (Andrea Kuluncic, Liesbeth Bik and Jos van der Pol, Stefan Keller, Carey Young).

János Sugár (b. 1958), a disciple of the late Miklós Erdély (1928-1986), the legendary and for many years unfairly silenced figure of Hungarian art, set up a caravan in Moszkva tér and entitled his project, Time Patrol. As he puts it, “On Moszkva tér, everybody who can dictate uninterruptedly by heart for 10 minutes to a typist in a caravan receives 4,000 forints.”

For the sake of comparison the average hourly fee in Hungary is between (500-1,000 HUF/Hour). The texts are transcribed and published in a paper, entitled “Time Patrol”, which can be purchased exclusively at the newsagent’s on Moszkva tér for 400 forints.

Sugár continues, “My aim is to produce a documentary whose future value is incalculable – exactly because it does not seem to be of any significance in the present. What we wouldn’t give to have an accurate transcription of a random conversation in a mail-coach at the beginning of the 19th century!”

By Hungarian standards, the money that Sugár is offering is a significant sum for 10 minutes of work, so there is a line in front of the caravan when it is expected to be in operation. And to give money at Moscow Square is a sensitive issue, to say the least.

Also, the people who are giving dictation do not really know why they are being asked to do it. The artist is using them for a vague purpose; an incalculable future value is being secured for a very precisely definable present value, with the help of the participation of everyday simple persons.

This relatively significant money compared to the time it required forced people badly in need to dictate and to sell what they had. And they do not have anything else but their poverty. They sold the stories of their poverty. The texts and stories of the illegal, poor, mainly Transylvanians are moving, I must admit.

However their stories are numbered in the publication, they do not have names, and all these do not bring any change in the attitude of the artist and the situation, the artist is using them for his own purpose and he is not giving voice to them. Seemingly, this task of giving dictation involves an interaction between the artist and any individual who participates.

It is a purely abstract relationship between the parties: Someone enters the caravan, dictates, receives the money. Sugár tacitly enforces the public notion that art is mystical, vague, something that does not make sense, especially contemporary art, which is seen as particularly incomprehensible. No one understands it, and it is incalculable.

Even if he is expressing this concept ironically, the reception of his work and the way that he uses people for his own purpose should be considered. Intentionally or unintentionally, he is thus playing the role of the heroic artist, and the work is ultimately based on the exceptional, unique role of the artist: The artist who volunteers to be a chronicler for the future, who believes in the romantic artist whose work will be discovered retrospectively and thus works for posterity and not for the present.

As he himself has often recently remarked, there is a need for attention, for greater attention to be paid to art. One cannot help wondering if the money served only to raise attention.

Money is strongly involved in another project as well. One can hardly cross Moszkva tér without being approached by beggars. Balázs Beöthy (b. 1965) inverts this common situation. Beggars asking for money are now distributing money, working to convince passers-by to accept the offered money.

Giving and taking money (or refusing to give it) are everyday forms of social interaction in the square. Inversion helps to throw into sharp relief this kind of communication. The beggars are carefully chosen, since they should be “professionally” good, but randomly chosen since the artist should avoid being cheated in any way.

They are “professionals,” who at the time of their selection do not yet know what their assignment will be; they get paid for their participation. Neither is the exact time of the action announced, so the beggars of the square cannot conspire and foil the project of the artist.

When everything is together, the artist documents the money-giving action. With the help of real money, communication, persuasion, interaction that are shown. The artist takes up the role of the anthropologist and investigates begging and persuasion as forms of communication.

As in science, inversion is a method of investigation. Also, the act itself is a nonsensical, a “counterfactual”, hypothetical thesis; what results from it should be “pure,” “essential” communication. The problem is that people are used and watched by the artist and by us. The “professional” beggars get paid for the performed work, but money still remains a sensitive part of the project.

The amount that the beggars are giving out in the course of the action is almost symbolic, but beggars are always asking for small change, so there is no such small amount that can be taken merely symbolically by a beggar. I couldn’t help wondering how someone who doesn’t have money 364 days of the year feels about giving money away on one special day of art?

Or how does it feel to accept money from someone who normally needs our money? How good is a beggar when acting against his/her usual habit? We do not get answers from the work. The situation reminds one very much of a laboratory situation where no matter how hard scientists try, there is hardly anything of a “natural” situation. Thus what the tests primarily reflect is nothing else but the process of the test itself.

Theaforementioned Miklós Erdély often played with inversion, invented rationalistic approaches to irrational phenomena, took nonsense seriously, and treated serious matters as nonsense. Balázs Beöthy’s work similarly evokes this attitude.

Erdély’s ghost is haunting the square, not only in artistic attitudes, or in Sugar’s person, but also in the presence of an object. The artists, Liesbeth Bik and Jos van der Pol from Rotterdam put a bronze box at the square. The box is a remake of Miklós Erdély’s work, Unguarded Money.

During the 1956 revolution, Erdély placed boxes in the streets of Budapest to collect money for the martyrs of the revolution. The purity of the revolution was evident, for the money was collected unguarded. The new box was basically supposed to be a catalyst of interactions, talks, even a series of talks in a daily radio broadcast.

At the opening, some put money into the box, but in the course of passing weeks it became a waste-bin, and, as I write these lines, it is locked. It is tempting to take this outcome as a metaphor. Well-meaning foreign artists came without proper knowledge of the local context, referring to what they thought was the common national heroic-mythical history; it did not work, and now it is closed.

Public reactions form an important part of the story of Róza El-Hassan’s installed work as well. She placed a wooden sculpture of a seated figure-the naked skeleton of an earlier work of hers in which the figure was dressed in a chador-in the middle of the square where the unemployed sit and wait for temporary jobs.

She entitled her piece, R. is thinking of overpopulation (see interview with Róza El-Hassan for discussion of the theme of overpopulation). Róza El-Hassan has broken with the idea of the elevated public sculpture, and thus her figure is just another faceless participant in the life of the square.

This makeshift wooden figure however, was and was not acceptable for the people of the square as a sculpture. People put a hat on it, added a beggar’s tray or a plastic bag to be held by the sculpture. However, somebody found it ugly and expressed his dislike by brutally violating it.

Did the reaction reveal that the public itself is not mature enough for this new type of public art? Or did it reveal that the faceless inhabitants of the square understood and identified themselves with it and found it offensive? Could a lawsuit be initiated against the violator of a piece of art when that piece of art cannot be considered a traditional work of art?

Ilona Németh (b. 1963), the Slovakian, Hungarian artist set up two capsules in the square. The capsules looked like large lockers. One could climb into them; have a little rest inside. She designed a small place, a Capsule, a haven where one could temporarily withdraw from the busy square. Németh reckoned with the “dangers” of its being damaged and soiled. The local reception was that the capsules were used mainly by the homeless for shelter and storage of their belongings.

Ágnes Eperjesi’s (b. 1964) original project was to cover the advertisements and billboards of the square for one day. She applied for permission from the large corporations that have set up advertisements at and around the square. From most of the companies she received permission.

Unfortunately, to carry out this plan would have been very expensive, and it could be realized only in a reduced way. Eperjesi and her assistants put questions to passengers like, “How much commission do you get for parading a logo-ed carrier bag about long after you paid for the privilege?”

She tried to convince passengers carrying plastic bags with advertisements to exchange these bags for ones that were not advertising surfaces. Her work Advertisement Free Zone raises the public’s awareness against being unconsciously used for commercial purposes. One can only regret that the more ambitious and monumental version of the work could not be realized.

There is another project that had to be scaled back for financial reasons as well. The group HINTS (Institute for Public Art, Mónika Bálint and Eszter Ágnes Szabó) wanted to distribute food packages from a helicopter on the day of the opening. They could realize this project from the ground only. We cannot avoid the question, on what basis was the distribution of the finances defined, so that these ambitious projects could not be supported?

Other topics of works at the square included: Advertisements and communication (Andreas Fogarasi, b. 1977), the effects of the transition from socialism to capitalism (Andrea Kuluncic, b. 1968), free information, which was spread with the help of a special paper, Moszkva tér plusz (Péter Szabó, b. 1978 and Csaba Csiki, b. 1977), conflict management (Carey Young, b. 1970), and an anonymous project submitted in an e-mail message, “the clock on Moscow square should show the local time in Moscow. Neither more, nor less”-and it did for six weeks. (See descriptions of the works with photo illustrations at the website: www.ludwigmuseum.hu/moszkvater/projektek.htm)

Tamás St. Auby set up a stand at the square at given times and one could fill in a form, the International Parallel Union of Telecommunications Ballot, and could vote for or against joining the Neutral Weaponfree Near-East-European Fluxus Green Zone. It seemed a nice concept. Unfortunately, the public had no idea what all this meant. The Ghost of Liberty marked the end of an epoch, rendering this closure visible. It could be understood by everybody. But an exchange of significant glances or the romantic notion of the artist as exceptional human being do not work anymore.

On the contrary, the spirit of the ’70s seems rather presumptuous today. Together with the political changes, the exceptional importance of art and culture in the region has also faded. Gone are the “happy” days when one could even get imprisoned for art.

Imre Gábor (b. 1960) and Lajos Csontó’s (b. 1964) work was based on making portrait video-photographs of passers-by at Moszkva tér, asking them if they wanted to be part of a contemporary art project and get into a museum. They wanted to exhibit the video photographs as a tabloid in the Ludwig Museum.

The work is a cynical though perfect mirror of the schizophrenic situation of the present – public art subverts the art of the museum with the support of a museum. However, this mirror remained blind since their project was, ultimately, turned down by the board. And this too, probably, was not by accident.

[su_menu name=”Focus Public Art In Hungary”]