A Conversation with Ilya and Emilia Kabakov

Once the center of the Moscow circle of conceptualists, Ilya Kabakov has become one of the most highly visible artists working today. He was named by ArtNews as one of the “ten greatest living artists” in 2000. Throughout his forty-year plus career, Kabakov has produced a wide range of paintings, drawings, installations, and theoretical texts — not to mention extensive memoirs that track his life from his childhood to the early 1980s. In recent years, he has created installations that evoked the visual culture of the Soviet Union, though this theme has never been the exclusive focus of his work. Since 1989, all the artist’s work has been a collaboration with his wife Emilia Kabakov. See also the artist’s website http://www.ilya-emilia-kabakov.com/.

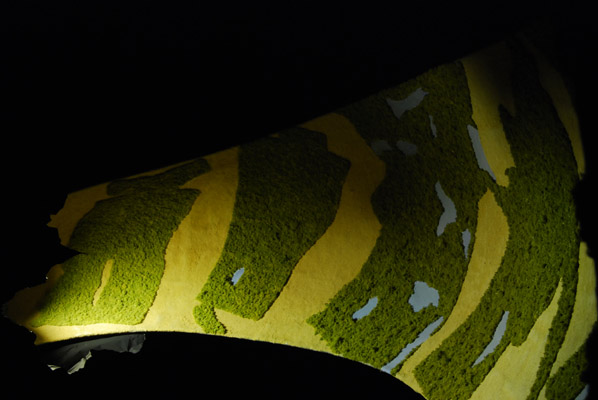

Katarzyna Bojarska: Let us start with your project for the exhibition in Atlas Sztuki. The title of this installation sounds very serious – WhatWe Shall See After Death. Where did the inspiration for such an eschatological perspective come from?

Ilya Kabakov: There is nothing serious about it. The greatest problem of art today is that there is so much seriousness. The artists walk around looking like prophets, so serious and self-important. They utterly lack a sense of humor, and it is impossible to have a normal conversation with them. We are not like that. We prefer self-irony in conversations with people, in relationships and in work, which is neither very serious nor totally playful, but is something in-between. While What We Shall See after Death deals with death, there is nothing grave in it at all. According to my very ironic prediction, the afterlife will be almost identical to our life here. We will see the same landscapes, the same banal planes. The only difference will be the deformation of the perspective. But this also has to be taken lightly. The bottom line is that this installation is very ironic, light, and pleasant. And that is the most serious part of it.

K.B.: Does the very medium of installation, or “total installation” for that matter, help to create this kind of lightness and irony you are talking about?

Emilia Kabakov: I would not say that the medium helps anything. Installations can also be extremely serious. It depends on the artist, on his/her relationship to art and art history. It also depends on how one actually perceives oneself, but that is a different story.

I.K.: The problem is also that having assumed this manner of irony in our relationship with others in art, we shift the burden of understanding to the viewer. A serious relationship seems much simpler. Traditionally, the viewer saw him/herself as a neophyte in front of an artist–prophet, as a rabbit in front of a snake, as a patient in front of a doctor, or, in contemporary terms, as a poor person in front of a wealthy one. And finally, the typical kind of relationship is that of a student and a teacher. The artist is talking and everybody else has to listen, no matter what.

K.B.: And this, I guess, is not the relationship you would identify yourself with?

E.K.: Not at all.

K.B.: What is then your idea, or ideal, of the relationship with the viewer.

E.K.: As we already said: very light, full of humor and irony.

I.K.: In a way, it has to be a philosophical relationship, the kind where we deal with the viewer as we would with a very close friend. We think that the viewer needs to be given the opportunity to decide for him/herself what exactly he/she is looking at. This grew out of our experience with Conceptualism and opposition to modernism. In this sense, conceptualism, being more reflective and intellectual, it is also more humanist. It was a humanist reaction against Modernism.

K.B.: Would you say that this kind of projected perception and what you expect on the part of the viewer is more what one would expect of a reader, that is a person reading a book rather than a person coming to a gallery to see a contemporary art show?

E.K.: In a way, the expectations are similar, but only if the book is good! A bad book just gives you everything. It grabs you and tells you how it is and what you should think of it. A good book, just as good art, makes you think, it teaches you to make your own decisions. And that is what we are constantly trying to do in our art.

K.B.: I want to go back for a while to the notion of “total installation,” which intrigued me when I read about it in your manifesto published by the Stedelijk Museum in the ‘90s. At that time, the medium of installation was still, as you claimed, a very young form of art. How do you perceive it now, nearly twenty years later? Is it more mature now? Have the viewers gotten used to it by now?

E.K.: It really depends on where you are, or even which city you are in. In some places people have definitely got used to installation art and have learned how to deal with it by now. They have accepted it as a part of the art movement. Sometimes they even understand the difference between an object, an installation, an object within an installation and a total installation. In some places, like contemporary Russia, for example, people do not perceive installation as art at all. They refuse to understand what it is. This can create a lot of problems. To give you an example: we had just opened an installation exhibition at the Hermitage in which a part of the installation was a false museum. First of all, they did not understand that it was us who built it, and second of all, that the paintings were not just paintings as such but were parts of this total installation. This whole mis- or non- understanding found its reflection in particular reviews which prove that the people who wrote them absolutely failed to understand what it was all about.

I.K.: The fact that they could not understand this piece proves that the type of mind we are accustomed to dealing with, the one which understands everything eagerly – at a certain level – might not exist in some places at all. In order to understand this, one needs to acknowledge that this problem is connected to certain things: to the notion of the intelligent mind and to the difference in understanding of the intelligentsia in Russia and the West. The idea of education and enlightenment was brought to Russia two hundred years ago. During the 19th century, Russian education and thought were moving in two directions: towards sciences and the humanities. The humanities were extremely important because they dealt with an image of the human being as one who deserved to be enlightened, deserved to be intelligent. An intelligent person, therefore, stood out from the rest of the generally uneducated society. In the 20th century, during and after the Bolshevik Revolution, the intelligentsia was almost completely eliminated. The difference between the two totalitarian regimes – the Nazis and the Communists – is as follows: the Nazis completely eliminated the intelligentsia, whereas the Soviets did not. According to the Nazis, the German race was the best and nothing else seemed worth remembering or studying, whereas the Soviets thought differently. They believed they had to inherit and use international knowledge. There were little islands of enlightenment amid the general ignorance in the Soviet Union: libraries, museums, conservatories, theaters, also art museums and systems of self-education. Young intellectuals in the Soviet Union found themselves confined but they believed they could find a tunnel of enlightenment, a connection to the universal culture. There were a lot of groups dedicated to self-education, especially in Moscow. This was a way of confronting the dominant power, but not in a political sense, because the politics were useless. It was a wave of cultural confrontation The reason I am discussing this at length is because it provides the background to the inception of a circle of Moscow conceptualists who, at least in part, grew out of this type of mindset, the intelligent mind. Unfortunately, today this tradition has disappeared almost completely. And that is why we assume such a distanced position towards contemporary art in modern day Russia. Russia today is a totally destroyed place.

E.K.: I do not agree with that diagnosis. My motto is to never say never. And I think that currently Russia is dominated by big money. But this situation is similar everywhere. Glamour and fashion dominate in Russia as it does all around the world. Many things are going wrong but it will pass. Change is inevitable. Right now the markets are falling and money might not be available to such an extent as it used to be. Fashion will stop being everyone’s top priority and that in turn will create a vacuum in which culture again will dominate. The only way to save ourselves during a depression is to start thinking again.

K.B.: Would you say there is nothing of interest in the contemporary Russian art scene?

I.K.: It is not only about contemporary art, it is about the general situation. What matters is not really what type of art dominates, but what type of artist. In order to survive in the contemporary Russian art scene, one has to be very aggressive and very focused on mass media. This ideal artist is the hybrid between a businessman and an artist. Such artists are not intelligent people. Modernism allows artists not to be intelligent: the artist can be a criminal, a genius, a spontaneous person but does not have to be an intelligent human being. The period in Moscow when the model of the intelligent mind dominated was a very short one. And now that time is over.

E.K.: Art in Russia is mostly back to performance, actions, videos, social projects. It has become more and more about the shock factor.

I.K.: It is no longer about distance, reflection and observation. Very dynamic and very animal-like.

E.K.: It is only that way today. It is art whose bond with contemporaneity is inseparable. “We want you to see us today!” That is what they all keep saying. If you forget about them tomorrow it does not matter because their art concentrates on what is happening today. It is all about the interaction between you and me today. What happens tomorrow belongs to the future and that is beyond their interest. They get their money today, they get their fame today. They take what Warhol said about 15 minutes of fame literally. They cannot even see the distance and irony in his words. They take literally what Beuys said: everyone can be an artist. They take everything at its face value because they lack distance and irony.

K.B.: Which seems kind of paradoxical if one thinks back on the Soviet Union and two realms of artistic activity: official and unofficial.

E.K.: Today every kind of art in Russia is official.

K.B.: And you have not found artists who would be politically engaged, intellectual and seriously treating their obligations, who would function on the margins of this official culture?

E.K.: Many people from the older generation have remained the same. How it works in the younger generation, frankly speaking, we do not know. I would not say yes or no, because I do not know. What we see is what is on the surface, and while the margins might exist, they are probably so small that one cannot even see them. Politics? Practically nobody is involved in politics on a serious artistic and intellectual level; it is a political charade.

I.K.: What is very important to us is the meaning of art. The meaning of what we do. What we do has to be meaningful. It cannot just be disposable. We do this in opposition to modernism because for us, meaningful art is related to literature. Whereas, according to the Modernist paradigm, literature is considered useless and a distraction from the visual element of art. For a very long time in modernism human feelings and thoughts were considered sentimental and were treated as taboo. And if a critic discovered that there was some “humanity” in an art work it was immediately labeled sentimental and not worth discussing. If it was pornography or pedophilia then it was fine, but not if it had humane elements…

The tradition of human feelings and respect for others has been present in Russian art and literature for a very long time. It is the tradition of attention paid to the simple man. And who is this simple man? He is a loser, a person who fails. Those who devoted their art to this kind of man, the individual we can identify ourselves with, were Gogol, Dostoevsky, Chekhov. But it was not just about losers. The idea behind all of this is that it is not one simple man who is a loser in this country, but the whole history of this country is the history of losers, of losing. This tradition deals with the constant destruction of utopia, which Russia constantly tries to build and constantly fails to achieve.

K.B.: What kind of utopia is Russia trying to build nowadays?

E.K.: It is a capitalist utopia.

I.K.: What it really is, is subsequent waves of losses.

K.B.: Having considered what you have just said about the Russian tradition, how would you identify yourselves as artists? Russian artists? Post-Soviet artists? Russian-American artists?

E.K., I.K.: International artists! Nationality does not matter here.

I.K.: Ours is always the viewpoint of an outsider, of a person who is always outside and looking in.

K.B.: Is the choice of such an artistic stance a lesson learned from 20th century history (and art history as well)?

E.K.: It is just a position that grows out of one’s character. It is hard to say. It might be a strength of one’s character or a fault of one’s character. For me this is a position one takes as a human being and as an artist – to look at life, at art and at others from the outside. It is the ability to always be ready to reflect.

I.K.: The difference between the 19th century intelligentsia and the 20th century intelligentsia in Russia is very radical. In the 19th century, they believed in change. In the 20th century, they realized that nothing could be done or changed and that the only position available to an intelligent person was to be on the outside, to be a viewer, and to reflect on the situation. He or she became like a patient in a hospital who can only take his/her temperature but cannot heal him/herself and cannot heal the others.

K.B.: What would you say is the role of the historical experience in your artistic work?

E.K.: It contributed to this reflective position, to the reflection on people’s achievements and failures.

K.B.: Svetlana Boym wrote of your work that it is a “museum of memory.” Would you agree with that? And if so, what kind of memory would that be?

E.K.: Of course we would agree. It is a human memory, a memory of a human being, it is also an artistic memory and a memory of the country.

K.B.: Is it concentrated on individual memory or does it rather deal with some collective experience and phenomena?

I.K.: There is no difference between personal memories and invented memories. It is all about images and metaphors. It is never actually personal or real, it is always metaphorical. Whether it is documentation or fiction, it does not matter. Image is much more important. Maybe people in the West do not understand what I am saying, but they have an experience and they know how to understand the structure, the medium and the visual.

K.B.: Would you say there exists any relation between your choice of total installation and totalitarian political system? Is there any link between the two?

I.K.: No, that would be naïve.

E.K.: It is too direct an association. Total installation is an artistic genre, a variation on the notion of the Gesamtkunstwerk; it is an experiment.

K.B.: What I meant is the relation between the total installation and, as you said, the fact that it was completely rejected in Russia, that it was not understood as an artistic concept. My question goes to the relation between this rejection and what one might call a mentality (individual and social) shaped by a totalitarian system.

E.K.: It would be very childish to say so. No.

I.K.: The power is totalitarian but the people cannot be totalitarian, otherwise there would be no totalitarian power. This is the paradox. Even if people succumb to the totalitarian power, it does not make them or their mentality, as you say, totalitarian.

E.K.: Just the opposite. Look what happened when the Soviet Union fell apart. Have you seen any totalitarian people around? Nobody wants the totalitarian system to be repeated.

I.K.: People are victims of the totalitarian power, they are never totalitarian.

K.B.: II am afraid you misunderstood me. What I meant to say is that a totalitarian system might create a certain kind of victim, if you like.

E.K., I.K.: No, it does not. It cannot, just think about it.

I.K.: Russia is a very chaotic country. It is actually more chaotic than any other country inthe world. There are no rules, no directions. It is incredibly chaotic despite its experience with totalitarian power. The official structure might seem totalitarian, yet everything else goes in whatever direction. One needs to understand Russia. It is not a monolith and therefore, it does not create a uniform type of mind. It is really difficult to understand.

Everyone thinks he/she is very complicated whereas the other is very simple. It is a psychological phenomenon: I am a four-dimensional person and the other is one-dimensional. This is so typical and normal at the same time. It is a colonialist point of view. The Western artist looks at the periphery as at something very primitive: Russians, Turks, and Africans are very primitive.

E.K.: Even Poles!

I.K.: Absolutely. For Germans or Englishmen everything that goes inside their cultural space is very complicated and advanced, whereas what is outside is wild and barbaric. We have lived in the West for 25 years now, and we have always received the same reaction: “Ah! You are Russian, let’s drink vodka together! Ha ha!”

K.B.: Would you say art has any possibility to change this situation, this state of affairs?

I.K.: Absolutely not. There is a center and there is a periphery. This is a very stable way of organizing the world. Everyone thinks I stand in the center and you at the periphery. France, Germany, England, America constitute the center of the world. Everything around that center is the periphery; it is impossible to change this.

K.B.: And yet the West loves the Kabakovs.

I.K.: No, absolutely not. It does not matter.

E.K.: They can like you, they can love you, they can put you on a pedestal, but they will always think “what a nice Indian artist,” or “what a great Polish artist.” They are not going to say: “what a great artist.” They will always create a label first, even if you are very successful. Unless you are so successful as to transcend local boundaries. In that case, they will say, “American artist born in Russia.” That is where we are right now.

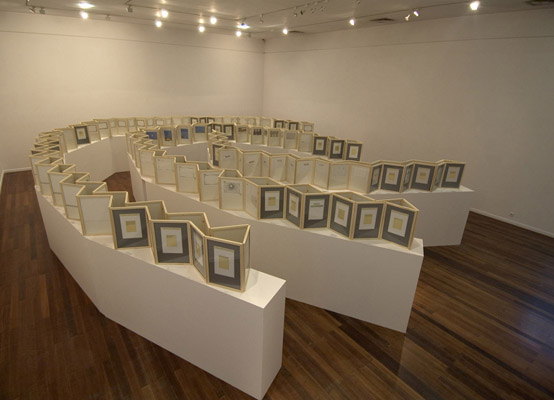

K.B.: I read about your project Alternative History of Art and found it very intriguing. Was your reflection on how art history and the art world work for the reason for starting this project?

E.K.: No, not really. It was more about Russian art, the ideas in Russian art, the combination of different artistic ideas. It is also an installation.

K.B.: How do you perceive the movements of writing alternative art histories, for example, the idea to write or re-write Eastern or Central-European art history?

I.K.: This is a very good question! There is no other history besides Western art history. It is impossible to write a parallel history: African, Australian or Central European. It all boils down to Western museums, galleries, and collectors.

E.K.: It goes back to what we have just said about the center and the periphery. Why does it have to be Eastern art history and Western art history? Why can’t one art history encompass everything? There are many Eastern artists who made their careers in the West and you cannot then reinsert themselves into Eastern art history because now they belong somewhere else. Take Opa?ka, for example. For me, he is a Western artist because he is very influential in the West. He is international. The same goes for me. Some people have made it into the realm of international art, and some have not.

K.B.: Would you then say that calling oneself a Polish artist or a Slovenian artist is a gesture of self-colonization, of pushing oneself into the margins, beyond the realm of international art?

E.K.: In a way, yes. I just hate this question: do you consider yourself Russian or American? We hope art does not function within national borders. On a certain level art is international. And if it is not there yet, we are in bad shape. There will always be local artists. If they can make it, if they can put their local ideas into an international context and explain them on an international level so that people everywhere around the world understand them, that means they are international. Why should you say Polish, Russian or American?

K.B.: What about women’s art in that context?

E.K.: It is the same thing. How do I see gay art? The same! I had an argument with a friend who is gay. I asked, “why do you push it in my face? Do you want me to notice that you are different? I do not care about this. For me you are a human being, a very intelligent and smart one. If you push your sexual difference in my face, you force me to dwell on them.” I do not see that you are a woman unless you point it out and you want me to know that you are doing it. If I talk to Marina Abramovic, I do not talk to her as to a woman artist, or because she is a woman artist, I talk to her as a great performer and a great performance artist. I do not need to know which country she is from or what sex she is. As a woman, she is my friend, as an artist she is a performer on an international level. That is all I have to know.

I.K.: The crucial question is that of the difference between the local and the international. What is the border? What are the criteria? In Russia we have very good, famous and rich artists, and no one knows of them outside of the country. And the other way around: there are many international artists not known locally. So what are the criteria determining what is local and what is international? For me that would be a formalist criterion: new, clear and very transparent. For example, Opa?ka is an international artist because he invented his own artistic idiom. Nobody creates in the same way, his is a new medium. The same goes for On Kawara.

E.K.: It is not only because their work is new, but because on the “international” level, they succeeded, they are there. You can see them in the museums of any country and you perceive their work as art.

I.K.: There are several levels one can distinguish in the art world: the money level, gallery and biennial level, academia level, and finally the museum level. The latter demands time, atmosphere, more attention and care. These might strike one as primitive distinctions, but that’s how it works most of the time. It is impossible for one person to operate on all of these levels.

E.K.: But I do not think that it is that clear. You can look at Damien Hirst as a market person or as the concept of a market person. Maybe his is a concept of being both the most expensive and the richest person in the world.

I.K.: The problem is that there are two parallel worlds: that of culture and that of reality. It is not possible to combine the two: money is for survival, culture is for the spiritual being.

September 2008

A version of this interview was previously published in the magazine Obieg, http://www.obieg.pl/.