Dreams Behind Bars: Miami’s “Russian Show”

Russian Dreams, Bass Museum of Art, Miami, December 4, 2008 – February 8, 2009.

Russian Dreams presents work by contemporary artists from Russia. On view at the Bass Museum of Art in Miami from December 4, 2008 to February 8, 2009, the exhibition is a collaboration between the Bass and the Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow. It includes work by established artists such as the AES+F Group; Alexander Ponomarev; Vladimir Dubossarsky and Alexander Vinogradov; Dmitri Gutov; Alexei Kostroma; and a new generation of younger artists including Julia Milner, Rostan Tavasiev, Haim Sokol, and MishMash Project. The first group came to prominence in the 1980-90s, the period of the Russian underground and of perestroika. The second, younger group of artists, currently between twenty and thirty years old, matured in post-perestroika Russia, at a time when government bans on personal expression had largely been lifted. The exhibition is curated (and competently introduced) by Olga Sviblova, the Director of the Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow and the curator of the Russian Pavilion at the 2007 Venice Biennale. “Russian” shows in which varying formations of “Russian” artists unite to present art that is somehow “Russian” have become all the rage in recent years. In Miami the last such show happened only two years ago, Modus R (curated by Olesja Turkina and Eugenia Kokhodze). Modus R and Russian Dreams demonstrate that Russia’s most powerful export article, apart from oil, is Russia herself, or rather its myth.

Like Modus R, Russian Dreams is an ironic companion-piece to the kind of art diplomacy with which the Russian government every once in a while charms the gullible Western European public (witness for example the massive blockbuster survey of 600 years of Russian art staged two years ago under the title Russia’s Soul at the Federal Exhibition Hall in Bonn/Germany). Where Russia’s Soul examined, well, the Russian soul and its soaring flight, shows like Modus R have generally tended to focus more on the Russian nightmare. Crucially, by choosing Russian dreams over Russian nightmares, the exhibition at the Bass brings desire into play. Not that the relationship between dreams and desire is uncomplicated. While dreams may convey to us what we (secretly) wish, we are rarely in a position to decipher that message with any degree of clarity. Russian Dreams offers ample illustration of that fact. In her remarkable series of photographs entitled Dream Street (2000), Olga Chernysheva presents Russia herself, literally, as a type of dreamwork. The artist shows a series of black-and-white photographs taken somewhere outside Moscow, in places where, according to the artist, “now they fight over every hundredth of a hectare and building work is in full swing.” The photographs show plots of land lined and marked by makeshift fences, gates, and other vertical and horizontal lines that divide the landscape, collage-style, into discrete segments. One of the photographs–remarkable in that it demonstrates how dreamwork turns words into puzzling riddles–shows a gate with a series of adhesive letters attached to the wood. Several letters have fallen off, and “Wood Street” (Ul. Lesnaya) has become “Dream Street” (Ul. sna).

Dreamwork at work: like the disfigured street name in Chernysheva’s photograph, a dream is an incoherent puzzle whose constituent elements need to be inserted into a latent, invisible series (the “latent dream thoughts”, in Freudian lingo) to make sense. Dream Street invites us to view the accidentally produced street name as an entryway into a landscape where ordinary logic gives way to the (visual) logic of dreams. This is another reason why there are so many gates and bars in Dream Street; it is as if the landscape contained “barred”, dreamlike areas whose decipherment photography has taken upon itself.

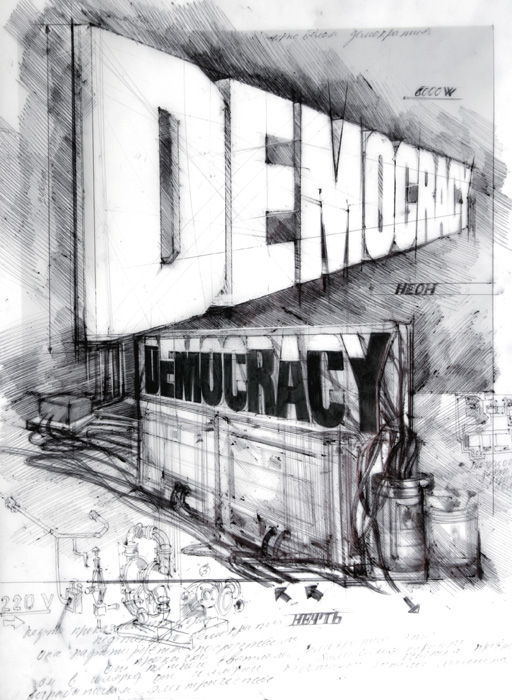

A crucial procedure for the analysis, in art, of myths and dreams is the appropriation of existing words and symbols. If conceptualism and sots-art of the 1970s and 80s undertook such an analysis by appropriating the symbols of Soviet power, contemporary Russian artists treat conceptualism—and the dominant modernist paradigm on which it is founded—itself as a dream and try to dissect that dream’s aesthetic, social, and institutional underpinnings. Alexei Buldakov’s sexually allusive animations of El Lissitzky’s famous poster Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge (Sex Lissitzky), complete with sound tracks taken from a porno movies, deconstruct the myth of abstract art by reading its language of abstraction in the register of (visual, not linguistic) commodification and exchange. If the result remains a bit of a one-liner (we learn little about the conditions under which this switch became possible, for example), the same cannot be said of Andrei Molodkin’s installation Democracy, in which large plastic letters filled with oil by noisy pumps spell out the word “DEMOCRACY”. The oxymoronic combination of a bar—suggestingcensorship and repression—with “democracy”–suggesting openness and freedom–again alludes to dreamwork: what appears in a dream often means the opposite of what it says. As Molodkin demonstrates so impressively, in a dream, a term like “democracy” may actually coincide with a “bar”, with censorship and with repression.

The position of the bar-like letters in front of the gallery’s right-hand corner is not coincidental. It was in a corner (a “loaded” space in Russian cultural history) that one of the leading Russian Futurists and proto-constructivists, Vladimir Tatlin, installed his first, revolutionary corner reliefs, fragments of the avant-garde’s dream that the future could become the present. By barring the visitor from entering the corner of the gallery, Molodkin blocks or “bars” this horizon. Of course, as Boris Groys has argued, the open horizon of the avant-garde was “barred” once before, by the likes of painter Erik Bulatov who painted words like “SKY” or “CPSU” into the open sky of their paintings in the 1980s. However, much like Western pop art with its ambition to reconcile mass culture with high culture, the sots artists subscribed to an essentially conciliatory aesthetic: their goal was to reconcile official with unofficial art. (This is why sots art appropriates the language of officialdom largely wholesale). Sots-art did not so much analyze dreams as it tried to find ways of prolonging the sleep without compromising itself ideologically (one of the physiological functions of dreaming is the prolongation of sleep). In his installation, Molodkin directly alludes to Bulatov, and to sots-art more generally, by installing the word “DEMOCRACY” in large letters on the wall behind the oil-filled letters on the floor. And as was the case in Bulatov’s paintings from the 1980s, these letters, their size diminishing to one side, seem to be disappearing into the white of the wall. However, in their competition with the three-dimensional letters in front of them, the letters “drawn” on the museum wall quickly reveal their illusionary quality, an illusion whose utopian “horizon” is nothing but the museum (wall) itself. With great skill Molodkin reveals that once we insert sots-art into a concrete institutional frame (the gallery or museum) and begin to interpret that frame, we quickly discover that sots-art, despite its revelatory pathos, is separated from its own signified the way the elements in a dream are separated from the repressed wish that occasioned them. Sots-art is “barred”: it is part of the myth, not its analysis.

In Celestial Forces of the Iron City (2008) Sergei Shutov uses barbed wire to draw the products of the once “closed” industrial town of Zheleznogorsk (known until the early 1990s only as Krasnoyarsk-26)—mainly rockets and sputniks—on the white walls of the museum. Like Molodkin, Shutov questions the representational practice of painting or drawing. The “dream” element Shutov picked for analysis, barbed wire, was part of a nightmare (Zheleznogorsk was built by convicts, we are told in the exhibition catalogue). However, the sign system in which barbed wire functions in Shutov’s installation is not primarily the GULAG (we learn about Zheleznogorsk’s link to it only from a commentary in the catalogue) but the museum wall that acts as the wire’s support and, by extension, the institution of art of which that wall is a part. In Shutov’s work, barbed wire acts as the (paradoxical, dreamlike) signifier for “drawing”, an accepted gesture inside the gallery that is associated with the kind of tolerance and freedom of expression to which the liberal art museum subscribes. To have that tolerance and that freedom be expressed by a sign that suggests the absence of freedom is to suggest, provocatively, that within the institution of the museum tolerance and liberalism may in fact themselves function as forms of repression. Once again, repression and censorship—the “bar”—appear as the indispensable, if unspeakable, conditions under which any liberal dream operates—in Russia and elsewhere.

In his installation entitled Shostakovich. In Memory of Sollertinsky (1993) Dmitry Gutov also uses (horizontal) bars, this time as part of the notational system of music. If democracy is «barred» in Molodkin’s installation, here it is music that is «behind bars». On Gutov’s bars, rifle cartridges are installed to suggest either flying missiles or musical notes, or both at the same time. As was the case with the barbed wire in Shutov’s work, the bars here function in two diametrically opposed ways: as symbols of war, aggression, and destruction, on the one hand, and of music and its notation, on the other. The ambiguity implicit in this operation is a common feature of dreams.

One of the fundamental effects of this ambiguity is that it makes Gutov’s installation essentially unreadable, just like like a dream is unreadable (are we looking at musical notes, or at rockets flying towards their targets on the ground?). And in this way the artist perhaps most capably sums up the goal behind Russian Dreams. That goal I suggest was less to illustrate or demonstrate the contents of “Russian dreams” but rather to show how dreams are seldom subject to straightforward interpretation. An instance of what we want, and thus of what most inalienably belongs to us, dreams also bar us from ever owning, or even understanding, what we desire. Gutov challenges the notion that music can be «read», just like dreams more generally challenge our ambition to read them literally. And this applies to dreams the world over.

One of the fundamental effects of this ambiguity is that it makes Gutov’s installation essentially unreadable, just like like a dream is unreadable (are we looking at musical notes, or at rockets flying towards their targets on the ground?). And in this way the artist perhaps most capably sums up the goal behind Russian Dreams. That goal I suggest was less to illustrate or demonstrate the contents of “Russian dreams” but rather to show how dreams are seldom subject to straightforward interpretation. An instance of what we want, and thus of what most inalienably belongs to us, dreams also bar us from ever owning, or even understanding, what we desire. Gutov challenges the notion that music can be «read», just like dreams more generally challenge our ambition to read them literally. And this applies to dreams the world over.