Examining the Excavations of History: Veronika Darian on the Genesis of the “Mind the Map!” Project

“An act of impudence marks the beginning.”With reference to the publication accompanying the project and reviewed in the current issue of ARTMargins: “Mind the Map! – History Is Not Given. A Critical Anthology Based on the Symposium,” eds. Marina Gržinic, Günther Heeg, and Veronika Darian (Revolver, 2006). See especially one of the prefaces, from which this sentence is borrowed, l.c. p. 23. That’s how it started, some years ago in Ljubljana, Slovenia. In 2000 the Slovenian painters’ collective Irwin, ie, part of the artists’ collective NSK: Neue Slowenische Kunst (New Slovenian Art) since 1983, initiated a project that would usually be assigned to a historiographer’s sphere of responsibility. This project, called the “East Art Map” (EAM), aimed at nothing less than drafting a chart of the most important artists and art works from Eastern Europe between 1945 and 2000, modeled on the Western historiography of art. In this vein the EAM entailed both a provocation of the official Eastern perspective on (art) history and a challenge of traditional Western self-conception and self-consciousness.

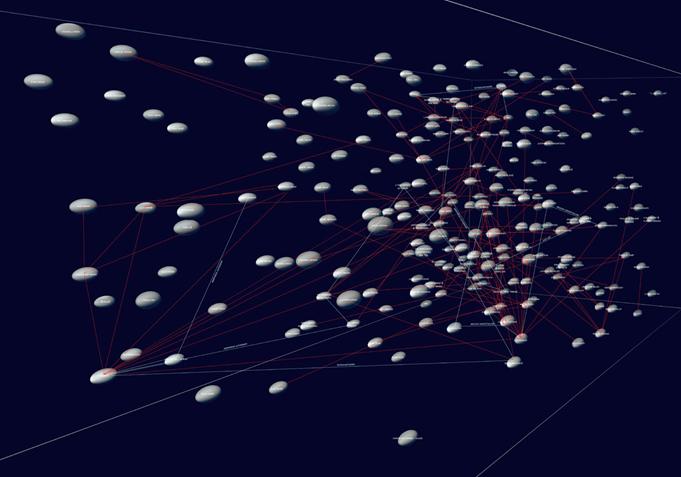

From the outset, the project of the EAM was shaped by the integration of experts who were invited to take an active part in the constitution of the map. In the first step, curators, artists, and art critics from Eastern Europe were asked to select significant artists and important works from their particular national contexts. In order to make their (subjective) selection (objectively) comprehensible they were requested to account for it by displaying their criteria and putting the range of works into international correlation. The outcome, a galaxy of associated works and networked artists, was presented in a special issue of the New Moment Magazine in 2002. After this, the second step followed: the EAM was installed as a public platform on the Internet in 2004.www.eastartmap.org. At this point the projects’ initiators called on Internet users to replace the presented artists or art works by others who were, from their perspective, more important ones, provided that they would give reasons for their new proposals.See also the recently published book: Irwin, eds., East Art Map: Contemporary Art and Eastern Europe (Afterall Books, 2006).

From the outset, the project of the EAM was shaped by the integration of experts who were invited to take an active part in the constitution of the map. In the first step, curators, artists, and art critics from Eastern Europe were asked to select significant artists and important works from their particular national contexts. In order to make their (subjective) selection (objectively) comprehensible they were requested to account for it by displaying their criteria and putting the range of works into international correlation. The outcome, a galaxy of associated works and networked artists, was presented in a special issue of the New Moment Magazine in 2002. After this, the second step followed: the EAM was installed as a public platform on the Internet in 2004.www.eastartmap.org. At this point the projects’ initiators called on Internet users to replace the presented artists or art works by others who were, from their perspective, more important ones, provided that they would give reasons for their new proposals.See also the recently published book: Irwin, eds., East Art Map: Contemporary Art and Eastern Europe (Afterall Books, 2006).

Gradually different problems became apparent with this editorial process: in the first phase it became obvious that most of the selectors neither established a relation between the local and the national artistic production nor applied all the same criteria for their selection; in the second phase the users of the Internet platform regrettably refused to accept the offer of democratic participation at all. According to these “failures”– an absent context for a comparative art historiography and the deficiencies of active participation – Irwin consequently decided to establish such a context for the productive use of the previous results on their own. Hence, the university network “Mind the Map! – History Is Not Given”For further information please see www.mindthemap.net. as collaboration between Eastern and Western European institutions was born. Since 2004 it aims to continue the EAM project’s research on the field of art theory and art history in the form of a challenging co-operation between young scholars and professors, arts and sciences, the academic and the public sphere. In the framework of and supported by “relations,” a project initiated by the German Federal Cultural Foundation, Irwin invited the Slovene curator, artist, and art theoretician Marina Gržinic to guide this university co-operation. Together with “relations” and the Institute of Theatre Studies of the University of Leipzig, especially the professors Günther Heeg and myself, this international network was founded. It was displayed for the first time at a symposium of the same title that took place in Leipzig in October 2005.

Examining the Excavations

The structure and the whole concept of the symposium revealed the different perspectives of East and West that the co-directors of the project aimed to put up for discussion. The invited university partners, namely Beatrice von Bismarck (Leipzig), Ekaterina Degot (Moscow), Grzegorz Dziamski (Poznan), Michael Fehr (Hagen), Werner Fenz (Graz), Marina Gržinic (Ljubljana/Vienna), Günther Heeg and Veronika Darian (Leipzig), and Miško Šuvakovic (Belgrade), were each asked to propose competent scholars to participate in the project. Finally, two young scientists from each invited institution were selected and paired – one from the East with one from the West – within the panel structure of the symposium’s lectures (14 scholars altogether). Beside this – and definitely not standing aside – the invited artists Clemens von Wedemeyer, Marc Tobias Winterhagen, Konstantinos A. Goutos and the performance group frankfurter küche (together with participants from Sofia, Bulgaria) showed their works, while the whole venue – an old ballroom, fringe theater, and cinema – was arranged by young artists from the Academy of Visual Arts (HGB) in Leipzig.

It turned out that there were many things to unearth and to discover during the project’s development. For example: What is meant by the terms Eastern and Western art, and how are we going to understand and use them? What is our, the Western, deep interest in the co-operation with the East? What are we to make of the interest of Western institutions like “relations“ as financed by the German taxpayers’ money or academic institutes like the Institute of Theatre Studies, institutions which usually remain in the secure frame of scientific disputations? What kind of interest is indicated, if not again a colonialist and benevolently integrative one from the position of a predominant big Western brother? And in which way can the Eastern partners relate themselves to these questions and to the temporarily apparent ignorance on both sides? (At one of the last meetings of the Eastern and Western project partners of “relations” Iara Boubnova, a curator from Sofia, noted that the widespread accusation against the West, which is that it knows nothing about the East, has to be supplemented by the following: “what the f*** do we know about the West?“) So, what could be saved through all the resentments, prejudices, meanders, and dead ends? And what is going to be left over?

The Overburden and Other Remains

The Overburden and Other Remains

For sure, “the East” no longer serves only as a geographical demarcation, but also as a metaphorical one, even as a definition of what could be called marginalised, invisible, hidden, or inaccessible. What possibly started as a project with a promising reputation – it is almost unnecessary to mention the enormous current hype about Western projects with an Eastern focus – taught the project partners less about “the other” than it did about themselves. Besides this, it was necessary to realize that the projects’ aim to build a platform for the discussion of artistic and cultural productions that converge around the axis of Eastern and Western art is definitely too large and too complex to be realized in only one event. The different structures of the art markets in the participating countries (including art theory and art history, as well as artistic practice) are reflected in specific difficulties: On the Eastern side these problems are often displayed as a lack of institutional security, regarding the finances as well as the organizational structures; for Western institutions the biggest problem seems to be not to deal with clearly defined projects (such as an exclusively scientific symposium or a separate artistic event) but with in-between-formats. Projects that are trying to cross or enlarge the borders of disciplines between arts and sciences – or between Eastern and Western needs – often cannot be supported because they mostly do not fit into the demands of such institutions.

As a preliminary result our suspicion is confirmed: the field of exchange between Eastern and Western perspectives has to be defined as both a field of interest and a field of struggles. There is a vision of a fruitful continuation of the project: being on par with each other, questioning the hegemonies of thinking and speaking about art and culture in the past without creating new hegemonies in the present or for the future.

For this essay the metaphorical field of mining as a frame and a thread was not chosen by chance; on the contrary, Irwin themselves provided a prototype for the rescue attempt of the descending Orpheus: In 1985/87 they realized a project that was primarily planned already in 1980 by their partners in the NSK, the music group Laibach. For “Rdeci Revirji” (Red Mining Districts) they descended to the underworld of the coalmines in the industrial area of Trbovlje, Slovenia. While Laibach were still banned from performing in their homeland Yugoslavia, due to, inter alia, their use of Fascist and Stalinist symbolism, the Irwin exhibition under the ground focused on the buried historical layers of Socialist Realist workers’ iconography. Till nowadays the exhausting and painful effort of such excavations has been carved on the projects of Irwin as if they had been chased by the “Apparat” in Kafka’s “Penal Colony.”

Another artist’s project bares a different trove: In the video work “leftover” by Jakup Ferri from Prishtina, Kosovo, the artist is digging a hole in the ground, a deep hole, in which he is going to disappear during the work; others have to help digging, while the mound of the excavated ground grows ever higher. Finally (after about ten long minutes) the artist and helpers start to fill all the soil back into the hole. They shovel without ceasing, apparently to restore the situation to the state in which it existed before starting this useless attempt. But – what surprise! – the excavated hole is too small for the excavations. There is always a bit too much leftover when one makes a trip to the “gorges”It reminds one of the numerous exhibitions that show a very special image of the formerly marginalized East European Art Scene. See In the Gorges of the Balkans: Europe’s Art and Cultural Scene (Kassel, Germany: Kunsthalle Fridericianum, 2003). of everyone’s own history.

Another artist’s project bares a different trove: In the video work “leftover” by Jakup Ferri from Prishtina, Kosovo, the artist is digging a hole in the ground, a deep hole, in which he is going to disappear during the work; others have to help digging, while the mound of the excavated ground grows ever higher. Finally (after about ten long minutes) the artist and helpers start to fill all the soil back into the hole. They shovel without ceasing, apparently to restore the situation to the state in which it existed before starting this useless attempt. But – what surprise! – the excavated hole is too small for the excavations. There is always a bit too much leftover when one makes a trip to the “gorges”It reminds one of the numerous exhibitions that show a very special image of the formerly marginalized East European Art Scene. See In the Gorges of the Balkans: Europe’s Art and Cultural Scene (Kassel, Germany: Kunsthalle Fridericianum, 2003). of everyone’s own history.