PRAGUE BIENNALE 1

|

|

Museum of Modern & Contemporary Art, National Gallery, Prague Veletržní Palác, Praha 7 – Holešovice, Dukelských hrdinu 47, 26 June – 24 August

It is always tempting, with such overblown events as international art biennials, (and the Prague event claims to be the biggest contemporary art event in Europe this year) to look for an image that somehow “sums things up.”

For the organisers of Prague’s “first” Biennale (iIn fact there have been other self-styled biennales in Prague. * In particular The Biennale of Young Artists “ZVON,” run by the Prague City Gallery.)* this emblematic figure is a digital makeover of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa by Jean-Pierre Khazem.

For myself, it is rather the curious tableau from one of the exhibition’s Czech curators consulting, via cell phone, with his Italian counterpart about the arrangement of one of the installations.

I say that the tableau is curious, and indeed it is in certain respects emblematic of the Biennale as a whole.

The Czech curator was standing outside the exhibition venue, refused access on the orders of the Biennale’s president, whilst his Italian counterpart, inside the building, had the unenviable task of interpreting between circumstances as best he could.

Little of the exhibition itself seemed to sum up the theme “Peripheries Become the Centre” quite as incisively as this burlesque of art institutional politics.

Unless one is to count the almost bizarre series of self-advertisements produced in the name of the Biennale by its Flash Art sponsors-one of which, in the Flash Art Newsletter of 23 July, achieves almost Kremilinesque heights of paranoid accusation vis-à-vis the Biennale’s detractors:

“Who dares to criticise us?” (“The half-hearted and skeptical are those who didn’t see the Biennale and the very well documented catalogue or those who do not understand how to organize a big exhibition of today’s art.

Are the half-hearted and skeptical those artists that saw their gigantic projects on a 70-meter wall reduced to leave room for the others?

Some reversed photo in the catalogue? Some wrong caption? Some curator and artist mumbling because they are unhappy with the place of with equipment taken away by one of their colleagues?” [sic])

It is of course debatable as to whether or not this sort of thing is becoming of the organisers of an international project on the scale of the Prague Biennale (more so, as the Newsletter item itself carried no by-line).

And while the Newsletter‘s tone and its catalogue of petty indiscretions belie a degree of contempt for those who might express sentiments critical of the organisers, it also reveals a disturbing disregard for a number of those directly involved withthe organisation itself (among them, the curator Jens Hoffmann).

The editors of Flash Art, and the General Director of the National Gallery in Prague, ought to be more prudent than to sponsor this sort of conduct.

Of the exhibition itself, a number of features immediately stand out. The first of these is the unevenly edited exhibition catalogue, pages of which had (for the official opening) been torn out and pasted on the walls beside exhibits in lieu of proper labelling.

This is doubtless a consequence of the minimal budget set aside for the Biennale as a whole-allegedly US$100,000, half of which having been understandably taken up by Lauri Firstenberg’s numerous curatorial projects.

Perhaps the feature which detracts most from the catalogue, and which has affected the Biennale as a whole, is the all too casual recourse to trite formulae and the sort of pseudo-theory babble increasingly afflicting graduate arts seminars around the world (with their talismanic figures like Hardt and Negri).

In this way, the Biennale’s slogan “Peripheries Become the Centre” is explicated in terms of “the dissolution of the dichotomy between ‘periphery’ and ‘centre’ and to a liberation of plurality in terms of both identity and artistic practice.

The distinction articulated in this dichotomy has become increasingly irrelevant due to information technology, the mass media, migration, and nomadism.

The escalating phenomenon of globalisation and the seeming collapse of physical distances brought about by the Internet have changed the terms in which the relations between periphery and centre are negotiated, and even the definitions of what these two places are.”

This mechanical catalogue résonné rapidly becomes little more than a snorefest, as the overall formlessness of the Biennale itself is explained away as an attempt to come to terms with the ambivalent nature of such things as identity politics, consumerism, bio-informatics, etc.

None of this is particularly innovative and in fact represents a more or less established orthodoxy in terms of both art theory and art practice.

For all the talk of hyperrealism and advanced digital technologies (Firstenberg), there is surprisingly little here to do with the more “contemporary” explorations of new media.

Despite the curators’ claims, most of the work on display adheres, with few exceptions, to the sort of “categorical” expectations surrounding more traditional artistic genres.

The only noticeable work to engage with kinetics or the “cyborgian” condition, for example, is Krištof Kintera’s anthropomorphoid shopping bag, entitled “I Am Sick of it All,” loaded with packets of junk food and an animated cucumber, venting its melancholia with phrases like “Can you tell me what’s going on here? I’m totally miserable.”

The major preoccupation of the Biennale is, in the words of the organiser, the “new trends in painting,” comprising, among others, the section of the programme entitled “Lazarus Effect” curated by Luca Beatrice, Lauri Firstenberg and Helena Kontová-no doubt to indicate painting’s somewhat miraculous return from the dead. Reports of painting’s death have certainly been exaggerated, but no more than claims of its resurrection-as attested by the paucity of the work displayed in the main atrium of Veletržní Palác. Here, the first thing one encounters is an installation of easel paintings from Kostabi World, as part of the section entitled “Out of Order” (curated by Luca Beatrice and Flash Art‘s Giancarlo Politi) which “surveys contemporary art from Italy” (sic).

None of the pieces exhibited in the atrium even begins to take advantage of Oldrich Tyl and Josef Fuchs’s lofty nine-story functionalist space (which is a shame-one thinks back to the work of Schnabel, Basquiat and Clemente with something approaching envy or nostalgia here).

“Untitled” by Petra Mrzyk and Jean-François Moriceau-a 4x10m pop-art mural-is the only piece that confidently approaches the space.

It also has the virtue of being the only piece in the atrium not to be surrounded by stained or damaged walls.

Most notable among these “new” painters, however, are Paolo Consorti and Christina Graziani-both, conspicuously, Italian.

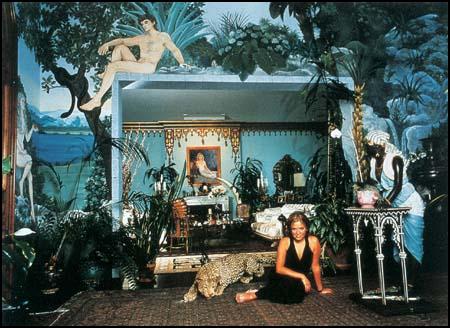

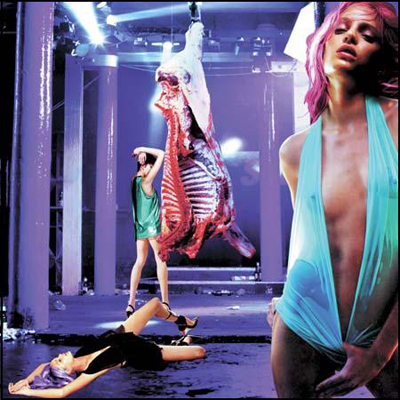

Graziani’s two-part meditation on post-punk/post-feminist carnality (“Untitled”) is arguably one of the most compelling works on show at the Biennale and has quite rightly deserved media attention elsewhere.

The focus in the main hall is the long video gallery-and while other parts of the exhibition space are air-conditioned (as visitors are warned), this part is not, making the viewing booths like sweatboxes.

Unfortunately the booths themselves are open to one another, producing a Babel of digital noise that compromises (or not, it is impossible to tell) the intentions of the artists.

Several of the digital projectors are defective, but of those videos not affected by technical malfunction the most inspired is the visual irony of Szabolcs Kisspál’s “Edging”-a “screensaver” video-collage of birds in flight rebounding off the inside edges of the screen.

Anton Vidokle and Christian Manzutto’s “Salto de Aqua” has the virtue of an Ellsworth Kelly-like visual austerity, linking the video screen to the cumulative reflection effect of high rise office windows-a “super dense grid” like a bank of surveillance monitors.

Among the documentary-style videos, Anibal Lopez’s “Una Tonelada de Libros, Tirada Sobre” (a truckload of old books and magazines being dumped in the middle of traffic on a main road in Mexico City) explores the nature of documentary and documentation.

The work examines the relation of event to representation, knowledge to information, etc. with a possible pun on the “information highway” as a type of American socio-economic fantasy run aground south of the border.

The one video that commands the most attention, however, is Gianni Motti’s “Untitled.”

It comprises a single live feed satellite transmission from the Whitehouse, showing George W. Bush preparing to announce Gulf War 2.

A voice-over in French acts as a running commentary, while subtitles in various languages announce “Attacks begin on Iraq.”

The video loop is disturbingly long, showing Bush being coiffured, licking his lips, practicing various facial expressions (all of them appropriately grave), and then grinning or winking at people off camera.

Unlike most of the other politically or socially orientated works, the novelty here is not solely in the subject matter, but in the impassive nature of the camera eye and its “perverse” function in the transmission and representation of truth.

Nearby, Jirí Cernický’s “Panasonic Emotions” and Štepánka Šimlová’s 16-part “I’m Terribly Sorry” assist the larger sense of irony attached here to such mediated displays of sincerity.

Too many of the photographic works on show depend upon ethnographic exotica and special pleading for their interest as art (images of asylum seekers on CD covers, for example, or portraits of street kids chez Nan Goldin).

Zwelethu Mthetwa’s interiors of workers’ shacks in Capetown stand out as powerful compositions in their own right.

Daniela Rossell’s “portraits” of high class fashion victims and Martéta Othová’s black and white “portrait” of a plastic dish with a view of Hong Kong printed on it, explore composition in terms of tableau.

Minimal in the case of Othová, gorgeous in the case of Rossell, but both engaged with a type of kitsch bathos.

The major drawback here is the awkward arrangement of many of the works: Othová’s 110x160cm print virtually abuts a wall-sized line drawing, while other pieces hang directly beside resident advertisements for a car showroom.

Amongst these works, Avdei Ter-Oganyan’s discrete installation of “bombs” (electric timers or alarm clocks wired to loaves of bread, cakes, lunchboxes, shoeboxes and packets of spaghetti) implant an element of comic relief.

The installation hints to the situation in Prague where the Radio Free Europe headquarters-a terrorist target, allegedly-remains surrounded by a cordon of armed soldiers, APCs, and concrete barriers.

Not so effective in its hard-attempt-at-parody approach are the Art of Survival and “Boycott Biennale” installations by Paula Roush and a collective of other British artists, located almost at the very back of the ground floor exhibition space.

Like much of the official sloganeering surrounding the Biennale, this just seems like a cheap attempt at postmodern “auto-critique.”

The fact that London is currently producing some of the most interesting artists on the international scene is, quite tellingly, impossible to gauge from the exhibition programme.

But then, major figures of contemporary Czech art, like Veronika Bromová and David Cerný, are also not represented-which is arguably justified, although the rationale for selecting artists, regardless of nationality, appears somewhat arbitrary overall.

At the same time, the work of trans-avant-guardia godfather Mimmo Paladino has been unaccountably enlisted in the service of the “new” painting (admittedly his canvases are among the strongest of those exhibited in the upstairs sections).

In the end, perhaps it would be best to propose another, alternative emblem for the curious hybrid that is the Prague Biennale: Kintera’s “Homegrown,” a 12m tall palm tree made from empty Fanta cans, rooted in a pot of sand littered with cigarette butts.

In other words, something quite large, possibly unstable, somewhat overbearing, thoroughly artificial, and bearing strange fruit.