Art and Politics in Black and White: A Comparative Study of Chile and Romania

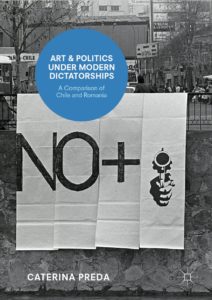

Caterina Preda, Art and Politics under Modern Dictatorships: A Comparison of Chile and Romania (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 323 pp.

Caterina Preda’s Art and Politics Under Modern Dictatorships: A Comparison of Chile and Romania proposes an in-depth study the author has been pursuing for many years, guided by an interpretive model that situates art as a reflection of political ideology. While acknowledging the methodological risks, Preda is determined to “untangle the relationship that develops between political power and artistic expression in dictatorial settings and which cuts across the left / right and the authoritarian / totalitarian categories,” (p. 6) in her comparative analysis of two nondemocratic regimes: Augusto Pinochet’s Chile (1973–1989) and Nicolae Ceaușescu’s Romania (1965–1989). Taken from extensive research into the historical, political, philosophical, and artistic material of both countries, Preda gathers a wide range of resources, from interviews to artworks, which constitute the book’s analytical core. In doing so, she attempts to link “the macro perspective of the regime, seen in the articulation of cultural policies, and the micro perspective the artists offer on reality through their artworks.” (pp. 2-3)

Caterina Preda’s Art and Politics Under Modern Dictatorships: A Comparison of Chile and Romania proposes an in-depth study the author has been pursuing for many years, guided by an interpretive model that situates art as a reflection of political ideology. While acknowledging the methodological risks, Preda is determined to “untangle the relationship that develops between political power and artistic expression in dictatorial settings and which cuts across the left / right and the authoritarian / totalitarian categories,” (p. 6) in her comparative analysis of two nondemocratic regimes: Augusto Pinochet’s Chile (1973–1989) and Nicolae Ceaușescu’s Romania (1965–1989). Taken from extensive research into the historical, political, philosophical, and artistic material of both countries, Preda gathers a wide range of resources, from interviews to artworks, which constitute the book’s analytical core. In doing so, she attempts to link “the macro perspective of the regime, seen in the articulation of cultural policies, and the micro perspective the artists offer on reality through their artworks.” (pp. 2-3)

Chile’s apolitical art plan and Romania’s overtly politicized art program are introduced by the author as dichotomous paradigms capable of providing new perspectives on “the study of art and politics with a double focus, on the one hand, on the institutional—the understudied field of the cultural policies of dictatorships—and on the other, on the role of artists and their artworks.” (p. 7) Although structured according to this binary focus, the book rarely merges the two countries into a synthesized reflection nor does it offer an intellectual speculation on their present relevance to the larger cultural sphere, the global political order, and today’s economic networks. The first chapter is an introduction into the aims and methodological approaches of the book, drawing together various references from the literature in the field, including Giovanni Sartori’s theories on modern dictatorship, Ian Kershaw’s comparison between Nazism and Stalinism, Sandrine Kott’s observations on the contradictions of the state apparatus, and Juan Lin’s typologies of totalitarian regimes.

Preda prefers the term “modern dictatorship” instead of authoritarian or totalitarian, in order to create a common ground for countries that elsewhere have been studied as part of geographical clusters. Therefore, the transcontinental comparison of dictatorships serves as a foundation for the many questions the author poses: “How is art imagined and affected by a modern dictatorship? What are the strategies imagined by the regimes and how are they built? How does the artistic space react, and how does it affect the political regime?” (p. 3) Preda’s argument for choosing these two case studies is based on the different strategies and instruments used by both countries to implement their official programs and to “alter art ideologically,” in the author’s opinion, regardless of political color. However, this argument proves to be insufficient for supporting a connection between Chile and Romania, and for providing a strong comparative framework for understanding one country’s context through the experience of the other.

The second chapter elaborates the main features of the political and cultural contexts in Chile and, alternatively, in Romania, treated in separate subchapters dealing with the economic models each promoted as well as the repressive systems they individually enforced. A similar procedure is applied in Chapter 3, a descriptive account of the official art in Chile. Here, the author meticulously documents the official cultural landscape of the Pinochet regime, following three categories: the ideological content of the policies and measures taken by the military junta; the restructuring of the existing institutions and the creation of new ones, such as the units of cultural affairs; and art and cultural production, divided into high art and mass culture.

The three tendencies concerning the cultural field – a nationalistic-authoritarian conception, the elitist traditional Catholic conception, and the neoliberal ideology focused on commercial cultural industries – are described by the author in relation to case studies such as networks of institutions at a central, municipal and local level, but also private associations, established in order to safeguard the cultural heritage and the national essence. A large space is dedicated also to the Cultural Program of 1975, which promoted an elitist culture, following a formalist approach and tolerating experiments with new media, as long as they were integrated in the “art for art’s sake” directives.

Surprisingly, Chapter 4 doesn’t continue with an analysis of non-official Chilean art, but with the mirroring research on the official art of Romania, which Preda presents at length, according to the same subthemes – the ideological project of the Ceaușescu regime, the institutional framework, and the artistic context, emphasizing censorship, homage art, and mass culture. The value of this section resides in the in-depth presentation of Ceaușism and its methods of enforcing the nationalist project according to the leader’s cult of personality and socialist reality. By detailing the directives pursuant to the July Theses of 1971 (a program of 17 measures aimed at the improvement of political-ideological and educational activity in the spirit of communist propaganda) and the prominent political and cultural figures who played key roles (such as Adrian Păunescu, leader of Cenaclul Flacăra, promoting folk music and poetry, and “state artists,” writers or filmmakers), the author engages nonfamiliar readers with the historical facts that distinguish Romania from the constellation of other communist countries.

At the same time, even for knowledgeable readers, parts of the account on institutional configurations prove useful for better understanding the political reforms that occurred during the 1970s and ‘80s. Chapter 5 returns to the Chilean context, this time presented through the lens of non-official art and alternative artistic positions. Confrontations with repressive institutions took different forms, including testimonial literature, documentary films, photography and body art. In the case of the multidisciplinary group Colectivo Acciones de Arte, who proposed a fusion between art and life. The author dedicates a subchapter to the activity of this interdisciplinary group formed in 1979 by artists Juan Castillo and Lotty Rosenfeld, sociologist Fernando Balcello, writer Diamela Eltit, and poet Raúl Zurita. The group considered everyone an artist as long as they dedicated their activity or mental effort to improving aspects of everyday reality. Their first collective action, Para no morir de hambre, took place in a district of Santiago, where members gave away bags of milk to the community to be returned empty for another art installation later presented in a gallery alongside recordings of a speech stating their artistic manifesto.

In Chapter 6, the author proposes a new excursion into the Romanian art scene analyzing its unofficial art through the concept of “aesthetic resistance” and its use of “double language.” Such a strategy opens up a larger discussion about how political or dissident art is defined versus what is merely an artistic experiment following an aesthetic agenda, which is often absorbed by revisionist art history as subversive gestures. Here, the book doesn’t provide the expected answer, as the author’s reiteration of the opposing terms political art and non-political art have already proven themselves to be critically impractical and limited in their capacity to cover a broader set of existing nuances on the ground.

Instead, Preda structures her artistic references in a “curated” manner around groups or types of artworks that share certain themes and visual sensibility. For example, the section Self-portraits as Accidental Subversion: The Artist was Free includes works by Báasz Imre, Rudolf Bone, Geta Brătescu, Teodor Graur, Ion Grigorescu, Ütö Gusztáv, Iulian Mereuță, Lia Perjovschi, Mircea Stănescu, Lászlo Ujvárossy. The subchapter Private, Apartment Art: Reality is a Myth brings together artists who participated in House pARTy (a two-part video and performance of non-public gatherings that took place in the domestic space of artists Decebal and Nadina Scriba in Bucharest in 1987-88); while The Forbidden Public Space and the Impossible Collective Action gathers actions by Alexandru Antik, Ioan Bunuș, Constantin Flondor, Károly Kovács, Paul Neagu, and Decebal Scriba.

The conclusions presented in the book’s final chapter struggle to find solid ground “Artistic resistance could translate to a purely aesthetic register in Romania, while in Chile it encompassed direct confrontation or ignorance of the official precepts.” (p. 308) The multiple types of marginality that Romanian and Chilean artists had to deal with (both inside and outside of their respective national contexts), and the variety of responses they received regarding exposure in those times (some works were tolerated, while others were not irrespective of their political content), could have been developed further by the author.

The inner reasons for the experiments that artists engaged with might have had something to do with a desire for a Western European synchronism, but also with an actual subversive attitude, which too often becomes a flexible category including non-official art production. That being said, although Preda’s research covers an impressive number of professional disciplines beyond the field of visual arts, including literature, film, theater, architecture, and television, and provides the reader with a comprehensive view of the selected period, in the end her interpretation is limited. Instead, Art and Politics under Modern Dictatorships offers a black and white image of a broader spectrum of fine gradations between official and non-official art.

Rather than providing a critical, in-depth comparison of the artistic scenes in Chile and Romania and, most importantly, the status of both countries in connection to other nations and regions, Preda delivers two parallel accounts. While the comparative chapters dealing with both countries take up a smaller portion of the book, the author too easily settles on relatively general and recurring remarks, such as: “Artistic expressions are paramount for dictatorial regimes due to their symbolic power, and they are used overtly by such regimes” (p. 314); “Art can be both a reflection of the political and a critical reflection of the regime, as it employs a language that deconstructs the official perspective and advances an alternative” (p. 315); “The artist is a privileged witness to dictatorship as he or she can change our perception through the details that are selected to portray the shared experience” (p. 316).

The reader may believe that the fundamental ambition of this study is to find the right framework to reposition the artist as a cultural producer, beyond the overly simplified categories reiterated in most existing studies – namely, to make a clear the division between art that is complicit with the regime and an art of opposition. Instead, this path remains open and readers are put in the difficult position of drawing their own conclusions, besides the modest ones that Preda insists on: “Artistic renderings also show how personal experiences of life under dictatorships achieve a universal meaning through the prism of art.” (p. 303)

However, Art and Politics Under Modern Dictatorships may function as a catalyst for long-overdue debates over the nuances and subtle entanglements between the cultural production during the times and regimes under review, and the many ways it has been labeled and neutralized, acknowledged and rewritten, first by official state policy and more recently by narratives from the West and global North. This subject would have benefited from a different balance in the structure of the research, as well as more comparative analysis of the networks and connections that developed more or less clandestinely in both countries during the period analyzed. Recent studies, such as Networking the Bloc: Experimental Art in Eastern Europe 1965-1981 (Klara Kemp-Welch, Networking the Bloc: Experimental Art in Eastern Europe 1965-1981 (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2019). ) by Klara Kemp-Welch, concentrate exactly on the transnational influences and travelling ideas that redraw the geographical map of Eastern Europe as a conceptual flow of contacts, relations, and connections, some tolerated by dictatorships, others finding their way underground. While admirable, the aim of extracting Romania from the family of other Eastern European countries – the framework most studies have used – Preda’s book does not adequately serve multiple artistic positions. As a result, artists who chose the road to exile or those who positioned themselves in an assumed inner exile fit neither of the categories defined here. Cases of almost schizophrenic artistic attitudes and the “islands” of freedom of expression are not so much exceptions, as they are the internal paradoxes of the communist regime, complicating further the entire conception of the book.

Even in this admirable effort by Preda, still underrepresented is the long and complicated relationship both countries had with the so-called center. Besides the existing studies on the relation between center and periphery within the artistic field, a closer look at the power relations and the social and economic conditions carried out by colonial dominations would shed some light on aspects of both countries’ historical background and current status. In a recent book published in Romanian, but based on previous writings in English and German, Manuela Boatcă (Manuela Boatcă, Laboratoare ale modernității: Europa de Est și America Latină în (co)relație (Cluj-Napoca: Idea Design & Print, 2019) argues for a reconsideration of the “laboratories of modernity” in Latin America and Eastern Europe, in view of their peripheral and then semi-peripheral status, and developments throughout their histories in relation to the capitalist world economy. In conclusion, perhaps it would be useful to reflect, in an integrated and more holistic manner, on the dependencies and connections of the two regions, which are not just consequences of dictatorial legacies, but also of inequalities throughout history.