Interview with Aneta Szylak

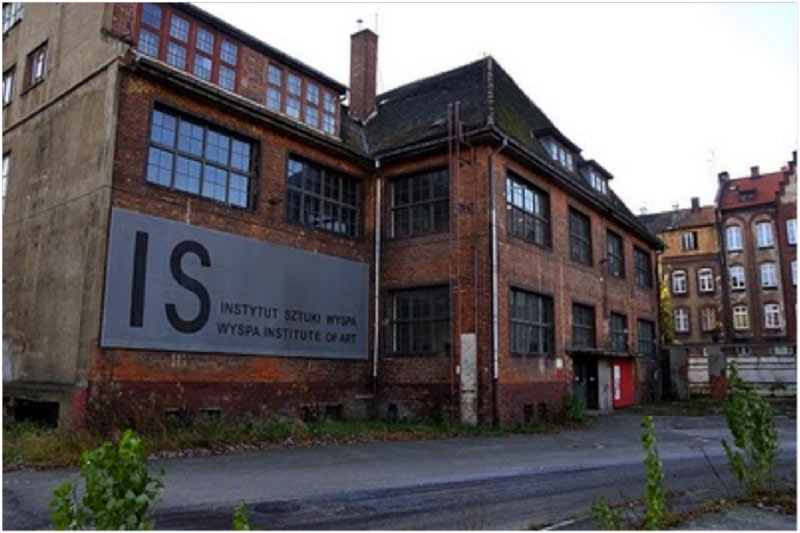

Aneta Szylak is a curator and writer, and co-founder and current director of Wyspa Institute of Art in Gdańsk. After co-founding and running the ?a?nia (Bathhouse) Centre for Contemporary Art (1998-2001). she pursued a career as an independent curator and researcher. In 2005, she received the Jerzy Stajuda Award “for independent and uncompromising curatorial practice.” Syzlak has taught and lectured at many art institutions and universities. including New School University, Queens College. New York University, Florida Atlantic University, Goldsmith College, and Copenhagen University. She held the position of a guest professor at the Akademie für Bildende Künste in Mainz. Currently she is finalizing her doctoral dissertation at Goldsmiths College in London and at the Copenhagen Doctoral School.

Aneta Szylak is a curator and writer, and co-founder and current director of Wyspa Institute of Art in Gdańsk. After co-founding and running the ?a?nia (Bathhouse) Centre for Contemporary Art (1998-2001). she pursued a career as an independent curator and researcher. In 2005, she received the Jerzy Stajuda Award “for independent and uncompromising curatorial practice.” Syzlak has taught and lectured at many art institutions and universities. including New School University, Queens College. New York University, Florida Atlantic University, Goldsmith College, and Copenhagen University. She held the position of a guest professor at the Akademie für Bildende Künste in Mainz. Currently she is finalizing her doctoral dissertation at Goldsmiths College in London and at the Copenhagen Doctoral School.

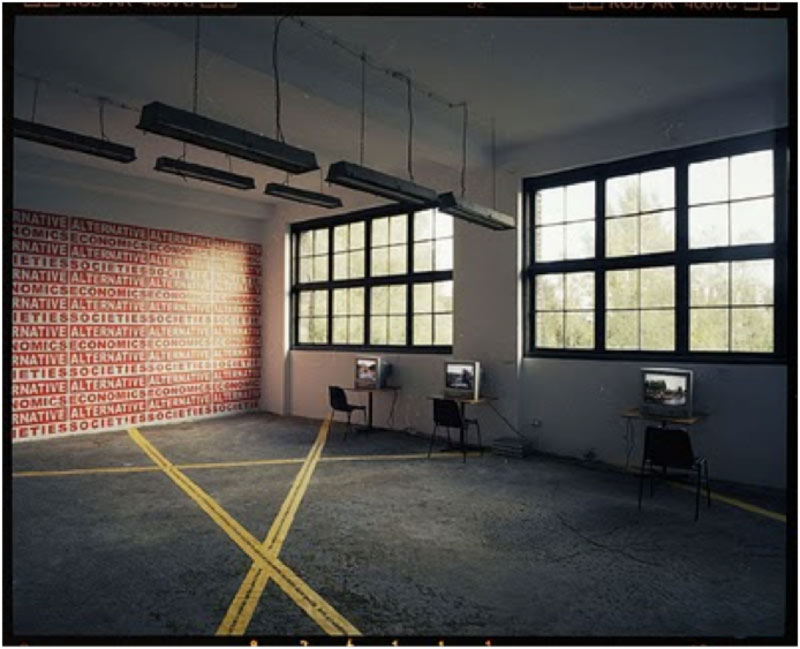

Subjective Bus Line, 2009. Images courtesy of Micha? Szlaga, www.szlaga.com.

Aleksandra Kaminska: Can you tell me a little bit about your background, as well as give an overview of Wyspa, touching on how Wyspa relates to other institutions in Gdańsk or other contemporary institutions in Poland generally?

Aneta Szylak: As an organization, Wyspa is one of the oldest artist-run organizations in the country. This [particular] location, I believe, is our fifth location in the city. Wyspa started in a very peculiar time in Polish history. It was founded by Grzegorz Klaman, an artist who arrived in Gdańsk in the early 1980s and is now a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts. That was just after the Solidarno?? movement was formed, which became a driving force in the social, political and economic transformation in Poland. As an artist at the time, you could either function within the regime or within the church, and not one of these ideological affiliations was attractive for the artists.

In the 1980s we can see several organizations in Poland, like a kind of self-organized compendium of groups and places that were trying to function independently from these dominant ideological forces, and Wyspa was one of them. There were some other movements at the time, for instance Tot-Art in Gdańsk, which was completely anarchistic, Dadaistic, and transgressive, as well as many others. So for Grzegorz and his friends, such as Kazimierz Kowalczyk or Eugeniusz Szczud?o, it was important to do something that was happening someplace else, or in a non-place, or in a place that was not defined and didn’t have a fixed meaning. And this place was Granary Island (“Wyspa”), andthis is where our name comes from.

Granary Island is very special to the city. It’s an undeveloped island on the Mot?awa river that was bombed during the Second World War and has never been rebuilt. The Island actually burned on numerous occasions from Medieval Times to the Second World War, because the supplies for storing grain were highly fragile and flammable. So “Wyspa,” Granary Island, is built on layers of burnt grain and salt and wood and bricks, and it’s a very interesting kind of calcified composite of different layers of the past.

In the shipyard there are also many layers of the past: [layers] that were, [layers] that remain, or [layers that] were scratched [out] or painted over. So I think this particular form of synchronicity in everything we see around us is very important. It’s the residue of the past, how we see it today and how we project it into the future. I think it was very important to go through this whole history, from the strikes, through martial law, the roundtable negotiations, a new democratic reality, and all the discontent that came from the way we perceive today’s reality of a new liberal economy and a democracy that turned out to be such a disappointing experience. We examine possible modes of self-organization, how we can maintain and perform our role in the public sphere, and how close we can be to the sphere of political practice. Wyspa is a political project. It has always been political [even if] it hasn’t always announced itself as such. It’s political in the way it combines fieldwork, research, activism, and the production and dissemination of knowledge. Our major concern is how we can be an active agent in contemporary public discourse.

In the shipyard there are also many layers of the past: [layers] that were, [layers] that remain, or [layers that] were scratched [out] or painted over. So I think this particular form of synchronicity in everything we see around us is very important. It’s the residue of the past, how we see it today and how we project it into the future. I think it was very important to go through this whole history, from the strikes, through martial law, the roundtable negotiations, a new democratic reality, and all the discontent that came from the way we perceive today’s reality of a new liberal economy and a democracy that turned out to be such a disappointing experience. We examine possible modes of self-organization, how we can maintain and perform our role in the public sphere, and how close we can be to the sphere of political practice. Wyspa is a political project. It has always been political [even if] it hasn’t always announced itself as such. It’s political in the way it combines fieldwork, research, activism, and the production and dissemination of knowledge. Our major concern is how we can be an active agent in contemporary public discourse.

AK: Could you give us an example where you think you were successful in engaging with the public or political realm?

AS: We make all sorts of projects, as well as exhibitions at conferences, publications, and different educational activities. So there are many examples, which are successful in very different ways.

AS: We make all sorts of projects, as well as exhibitions at conferences, publications, and different educational activities. So there are many examples, which are successful in very different ways.

In 2005, we made a project called The Dockwatchers (Strznicy Doków), which was our reaction to the emergent issue of memory in history and something that was later on named historical politics. The project dealt with how contemporary politics is seeking legitimacy in our common past, and how this implicates international relations and the image of Poland in the world. We had moved to the shipyard a few years earlier, so we already had this kind of vision of complexity, which you normally don’t see when you’re behind (outside) the gates.

What we did was to show a polyphony of voices, many of which we did not agree with. And I think that was a crucial element to this project. It’s a little bit like the way Dostoevsky writes his novels: he speaks through his characters, but he doesn’t identify with any of them. So it was important for us to have this polyphonic experience, the way Bakhtin writes about it. In The Dockwatchers we very much played with the fictionality of historic narratives, and we were dealing with different kinds of replacements—and even with dummies. Grzegorz invited a look-a-like of Lech Wa??sa and people went really crazy about it because you can’t normally approach Wa??sa, the former President, so closely. And to see this look-a-like inside the shipyard where people could touch him, talk to him… People werehugging, singing for him, sitting in his lap. It was extremely spontaneous I was swept away by the performativity and affect of this moment.

What was shocking for us in this project and other exhibitions addressing similar themes, was that they were interesting for almost everyone, young people and people interested in art, right-wing activists, and an older more conservative audience as well. That was really amazing because everyone recognized the critical potential of what we were doing. And I think the best thing was that it was not about agreement. We didn’t make a commemorative project. We showed the impossibility of commemoration, the impossibility of reconciliation with our past, and that was really a uniquely liberating experience.

What was shocking for us in this project and other exhibitions addressing similar themes, was that they were interesting for almost everyone, young people and people interested in art, right-wing activists, and an older more conservative audience as well. That was really amazing because everyone recognized the critical potential of what we were doing. And I think the best thing was that it was not about agreement. We didn’t make a commemorative project. We showed the impossibility of commemoration, the impossibility of reconciliation with our past, and that was really a uniquely liberating experience.

On a completely different note, there was the exhibition we made with Ewa Partum, a very important Polish feminist and conceptual artist whose career started in the late 1960’s. For me it was very interesting to make this project with Ewa who has an extremely strong personality. Today her biography and contribution to conceptual art can be contextualized, something we had a strong disagreement about. She made a significant number of works in the 1970’s and in 1980’s, related to the Berlin Wall and Solidarno??. The way she struggled with the kind of visibility of the female as a subject in the public sphere was very interesting for us. But, at the same time, we reexamined feminist thinking during the time of Communist rule. This issue is extremely interesting because the feminist movement is really very strong now and it’s a necessary thing in this new social and political reality when inequality is a fact, from unequal wages to unequal rights and ideological control over the female body. This is what you have now, yet we did not have this during Communist rule! Instead then we had completely different concerns. Of course, there was violence at home. Of course there were certain inequalities, but I think there were larger issues to debate. Also, because ideologically the Communist narrative supported female rights, in terms of women’s access to knowledge, access to power, access to labor and reproductive rights. For this project Ewa wanted to paint Wyspa white, as a way of going back to the practice of the 1960’s or ‘70’s. What we tried to show that there is a historic concern, a potential for looking at this from another perspective, questioning these kinds of strategies of isolation and purification that were typical of conceptual practice at the time.

Another project with Grzegorz Klaman was Subjective Bus Line, which we are now doing for a third time and which is again a kind of polyphonic project. This time former dock workers are running bus tours. We are using an old fashioned bus from Communist times. People really get into fights on this bus, and you can’t design or plan such behavior. It either happens, or it doesn’t happen. It depends on who from the group of dock workers is running the tour, what he/she says, and what kind of people are on the bus, At any rate, the tours often lead to major disagreements over history, the economy, politics, or Polish national heroes. This is a genuinely participatory project where the conditions the artist controls are very narrow. The workers have a lot of freedom in what they want to say, and you can’t control how people will react. They feel very free. Nobody films them, nobody records them…

Another project with Grzegorz Klaman was Subjective Bus Line, which we are now doing for a third time and which is again a kind of polyphonic project. This time former dock workers are running bus tours. We are using an old fashioned bus from Communist times. People really get into fights on this bus, and you can’t design or plan such behavior. It either happens, or it doesn’t happen. It depends on who from the group of dock workers is running the tour, what he/she says, and what kind of people are on the bus, At any rate, the tours often lead to major disagreements over history, the economy, politics, or Polish national heroes. This is a genuinely participatory project where the conditions the artist controls are very narrow. The workers have a lot of freedom in what they want to say, and you can’t control how people will react. They feel very free. Nobody films them, nobody records them…

AK: How do you think the younger generation of contemporary artists is addressing questions of the public, engaging with the public, or rethinking history? How are such efforts reflected in the activities going on at Wyspa today?

AS: We are trying to function in a “zone in between,” because we don’t want to make things ideological. We have certain concerns in relation to the mediating role of contemporary art. It’s not like we are only picking up works that explicitly deal with a political or ideological concern. We very often ask artists to contribute existing works and then we re-contextualize them. We are trying to build different narratives, critical engagement. We want to weave reality through the way we present contemporary art by making it active. There is a group of artists who do this kind of work. And it’s not just one generation. There is a generation of people who are in their twenties and thirties, and who are very busy reformulating the language of public debate. They do this in more directly discursive fields, such as literature, philosophy, or theory. So there are several parallel phenomena. Sometimes our paths cross and we do something together.

In 1989 we on the left were without a language because the left was so very connected to Communism, and there was no serious interest in society at that time to reformulate the language of political engagement. In a way we were just trying to inhabit the freedom of the public sphere, but we didn’t have any language for that public sphere. So we were all undergoing the process of figuring out how we can function in this reality, how we are going to understand this reality and our discontent, while at the same time knowing that the difference between the right and the left is no longer functional.

The way we work is connected to what Irit Rogoff discusses as criticality, which is when you are engaged in a process of critique and you are yourself entangled. So you are not positioning yourself outside by saying “this is bad,” or “that should be better.” We are situated inside of the reality in which we work. And the other thing that comes from Rogoff and that I like very much is the notion of smuggling. We are not being didactic, we do not want to correct reality. Ours is not an identitarian practice. It’s more a practice of what you might call “inhabitation.” And I strongly believe that, speaking from this position, we have a very interesting voice and it’s not at all about exploring new territories. I’m not interested in Polishness any more than, say, Kurdishness. Yet I do a lot of work with contemporary Kurdish artists from Northern Iraq. We made a couple of projects together over four years, but I’m not doing this to explore Iraq as another place of contemporary art. I think it’s a place we can learn from and this is what is interesting to me. But we are far beyond the exploration of unexplored territories.

The way we work is connected to what Irit Rogoff discusses as criticality, which is when you are engaged in a process of critique and you are yourself entangled. So you are not positioning yourself outside by saying “this is bad,” or “that should be better.” We are situated inside of the reality in which we work. And the other thing that comes from Rogoff and that I like very much is the notion of smuggling. We are not being didactic, we do not want to correct reality. Ours is not an identitarian practice. It’s more a practice of what you might call “inhabitation.” And I strongly believe that, speaking from this position, we have a very interesting voice and it’s not at all about exploring new territories. I’m not interested in Polishness any more than, say, Kurdishness. Yet I do a lot of work with contemporary Kurdish artists from Northern Iraq. We made a couple of projects together over four years, but I’m not doing this to explore Iraq as another place of contemporary art. I think it’s a place we can learn from and this is what is interesting to me. But we are far beyond the exploration of unexplored territories.

AK: In comparison with literature, visual art in Poland is largely mistrusted. How do you explain or understand this? Do you think it may be changing?

AS: I’m not sure whether trust is what we need. And I don’t think that culture is something we have to be at peace with. I think that that culture is here so we can deal with something that is unexpressed and unexplored in the field of political practice. My colleagues from other countries have said that it’s all about business and that we can do whatever we want because everyone knows that contemporary art exists in a sort of bracket, on the fringes. I’m not sure whether they would be so happy if they suffered asmuch as we do. We have limited access to public funds and we face difficulties with self-organization. Regarding literature I was thinking that during the Enlightenment and Romanticism, which were so important for the formulation of the Polish national narrative and Poland’s sense of statehood, we didn’t even have our own state. Poland was partitioned. We were kind of colonized. There was pressure mostly from Russians and Germans to erase our language. So what we had was the language and the literature. I think it was also partially a question of distribution because literature was easier to distribute than, let’s say, a contemporary art exhibition.

The other thing is that whatever a writer says is considered to be more legitimate than what a visual artist says. And we often see writers who are very much connected to a traditional vision of what this country is being hired by newspapers to criticize contemporary visual arts even though they don’t have any knowledge in this field. So many things are legitimate in literature and in theater but until now the intelligentsia here has not had the experience or the language to embrace contemporary art. And there is also a certain academic work that perpetuates this. For instance, in a famous series of publications, Trangressions, everything that was visual in those books was used to illustrate the debates of the literary field. For me, this was a very dangerous proposal in the way we consider the visual arts as an illustration. It’s a very narrow way of thinking about the contribution that visual art can make to public and cultural discourse.

AK: The Polish public and its mainstream institutions have traditionally conceived of visual art in a very linear way, as if it existed and could be understood on a singular plane. How do you see this changing?

AS: I think it is changing but it also dependents on the generation. Our public has grown younger. There is growing interest in contemporary art among college and even high school students. I think it’s opening up something and there are more and more people interested in debating contemporary art. And I remember that in the 1990’s we were one of the first groups who invited people from other disciplines to speak in the galleries. Now people who are doctors, engineers, philosophers, and economists are speaking and writing for cultural magazines, for discussion clubs, for galleries. So I think we are getting closer to a more trans-disciplinary approach and to thinking of art in a broader field, and that’s new.

AS: I think it is changing but it also dependents on the generation. Our public has grown younger. There is growing interest in contemporary art among college and even high school students. I think it’s opening up something and there are more and more people interested in debating contemporary art. And I remember that in the 1990’s we were one of the first groups who invited people from other disciplines to speak in the galleries. Now people who are doctors, engineers, philosophers, and economists are speaking and writing for cultural magazines, for discussion clubs, for galleries. So I think we are getting closer to a more trans-disciplinary approach and to thinking of art in a broader field, and that’s new.

AK: What is your relationship to the mainstream or mass media? Is that a sphere that you challenge, that you think of as a place of potential political engagement? Are you interested in how to engage with the media as a place of public debate?

AS: Yes, we do. Sometimes intentionally, sometimes not. As an organization we have a record for being scandalous and controversial. But we had a very interesting critical response for exhibitions such as Health & Safety or Dockwatchers, or now with the Lech Wa??sa Workplace, as with Subjective Bus Line. These projects have really created a kind of double response because they are at once being debated in art magazines as art projects, and in the mainstream media as something that they don’t really understand or know how to define. But it’s interesting also that these projects make something possible, and this is what we wanted. We didn’t want to stay in a ghetto of internal agreement within the field of contemporary art that says: okay, these are legitimate practices, we like them or we don’t; or: this was a successful project or this is not a successful project. We always wanted to reach out. Not through direct impact—we are not politicians—but in a seeping kind of way. We want to enable a conversation about something that we were not speaking about before.

AK: Do you think that the label “Polish art” is still a meaningful category for institutions, artists, and/or curators?

AS: I don’t think it’s extremely important to me being Polish. I think it’s important to look at how experience contributes to who you are and what that experience makes possible. I know that the experience I have—being born here, working here, having this kind of burden on my shoulders, a particular cultural and political background—is very important for what I can offer.

AK: Do you think the younger generation of artists in Poland is losing a sense of the importance of this local experience? So that what they bring to the table will not be different from what any other “global” artist might have to offer?

AS: Well, it’s hard to say but I think so, at least for a while. There was a project made about five years ago called Feelings are Always Local. It was about network culture, something that we always assume has no linkage to localities because we’re all part of a rhizomatic structure. But there is also always this (local) point from which you enter, and this is the point that interests me.

AK: Speaking of “locality,” do you think that Wyspa could have been developed anywhere other than in Gdańsk? How would you compare this particular city with other locations in Poland in the context of what you do?

AS: I am very involved in what can be called contextual curating, which means that I always acknowledge the way I am embedded in a setting. I work in exactly the same way in any other place. I made a project in ?ód? called Palimpsest Museum, and a completely different one at the historic museum in Pozna?. And I created the project Architectures of Gender at the Sculpture Centre in New York. This last work tried to understand how I mediate the reality I enter and that I am trying to inhabit. Of course, I have more competence here in Poland and I bear the burden of being here. However when I travel to work in New York, Berlin, or London, I use different layers of my competence. It always engages both something I find there and something I bring with me.

AK: In your curatorial work outside of Wyspa, do your interests shift, or do you continue this engagement with the public?

AS: Yes, I do. But of course, it’s a different mode of engagement and it depends also how much time I spend there. Recently I curated a project on the Edgware Road in London. This was interesting for me because of my experience in Iraq and because of the colleague with whom I made this project. When we got the offer to work at the Showroom in London, which is now located on Edgware Road and which has been a major settlement for artists from the Middle East since the 19th century, it was interesting for us to build this in a way so as to combine our experience in Iraqi Kurdistan with the experience of London. We wanted to figure out how we can deal with the complexities of belonging and not belonging. So how do you deal with a context in which you don’t belong, where your competence is narrowing because you don’t speak the language? We had to arm ourselves with completely different means of translation.

AK: Do you prefer working outside of the gallery space, or do you see any advantages in working within it?

AS: That really depends of the project. It’s not that I dedicate myself to the public space. I’m interested in the public sphere, but not that much inpublic space. I haven’t produced that many projects located outside. I’m more interested in how a project functions. But I’m also not that focused on producing one exhibition after the other. I’m more and more interested in how the process of conversation can be maintained. And I’m moving more and more into the field of participatory production.

AK: What can you tell us about your future projects?

AS: We’re getting ready for something that will be our project for the next two years. Hopefully it will be a reoccurring event that will be happening in Gdańsk every fourth or fifth year. It’s part of a big art get-together called Alternativa. It’s an investigation into how locally produced knowledge can contribute to the larger field of alternative thinking, how we can be organized and come together, and how the visual arts can help translate such thinking.

AK: Thank you for your time.

Gdańsk, March 2011